| Year | Population |

|---|---|

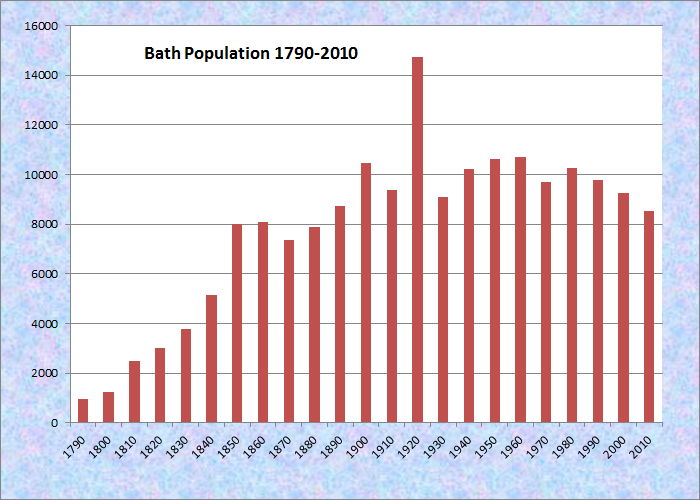

| 1970 | 9,679 |

| 1980 | 10,246 |

| 1990 | 9,799 |

| 2000 | 9,266 |

| 2010 | 8,514 |

| Geographic Data | |

|---|---|

| N. Latitude | 43:56:17 |

| W. Longitude | 69:50:15 |

| Maine House | District 52 |

| Maine Senate | District 23 |

| Congress | District 1 |

| Area sq. mi. | (total) 13.2 |

| Area sq. mi. | (land) 9.1 |

| Population/sq.mi. | (land) 935.6 |

County: Sagadahoc

Total=land+water; Land=land only |

|

Clipper Ships Built Here

- Monsoon–1851

- Carrier Pigeon–1852

- Emerald Isle–1853

- Flying Dragon–1853

- Undaunted–1853

- Viking–1853

- Mary Robinson–1854

- Windward–1854

- Pocohantas–1855

Bath Iron Works Shipyard (2000)

[BATH], the only city in, and county seat of, Sagadahoc County, named from the city in England, was incorporated as a town from a portion of Georgetown on February 17, 1781. According to George Varney, prominent early settlers were Christopher Lawson, Robert Gutch and Alexander Thwait, all of whom obtained land titles in the mid-17th century.

The Customs House was an important center for revenue and for recording the history of shipping in the area. Amos Nourse, a mid-19th century U.S. Senator, was collector of customs in Bath. The elegant City Hall, below, dominates the downtown and is a close neighbor of the Customs House.

During the Revolutionary War, a small battery on a bluff near the head of Arrowsic Island “repulsed” two armed British vessels in 1780.

In an early vote for separation from Massachusetts in 1807, it was only one of three coastal communities (along with Lincolnville and Belfast) to vote “YES.”

On February 14, 1844, it set off land for the formation of the town of West Bath. On June 14, 1847 Bath was incorporated as a city and later, in 1855, it annexed land from West Bath.

One of its early and famous residents was William King, Maine’s first governor. It is the birthplace of Freeman H. Morse, mayor of the city, state representative, and U.S. Representative; and the birthplace of Governor Sumner Sewall. U.S. Senator Amos Nourse lived in Bath in the mid-19th century, as did U.S. Representatives Benjamin Randall and Joseph Wingate.

Bath has had a long history of shipbuilding, including nine clipper ships during the 1850’s. In 1841, President William Henry Harrison visited one of its shipyards.

The list of labor unions in the city in 1903 reflects the local economy: Boilermakers and Iron Shipbuilders; Bricklayers, Masons and Plasterers; Carpenters and Joiners; Iron Moulders; Machinists; Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers; Riggers; Sailmakers; and Ship Carpenters.

The City is home to Bath Iron Works, a major builder of military ships with sophisticated electronic weaponry. Once locally owned, BIW is now a division of the General Dynamics Corporation.

In addition to the Kennebec River, on which BIW is located, the smaller New Meadows River forms the western boundary with Brunswick and once connected with the Peterson Canal.

Public sculpture, murals, historic architecture and more.

Sarah S. Sampson, tireless worker supporting Union troops’ health care needs during the Civil War, founded and served as first Matron of the Bath Military and Naval Children’s Home.

The Hyde School, a private institution, provides alternative educational options for students outside the traditional public school environment.

In the 1840s, long before Hyde School came into existence, Zina Hyde established his family’s estate on a picturesque 160-acre plot of land in Bath, and called it Elmhurst. His son, Thomas Worcester Hyde, served as a general during the Civil War and later founded Bath Iron Works. But it was the general’s son, John Sedgewick Hyde, who collaborated with renowned architect John Calvin Stevens and landscape architect Carl Rust Parker to design and implement the current mansion, its outbuildings, and surrounding gardens in 1913; at the time, the Hyde mansion was said to be one of the largest and most opulent buildings in the state. [A Bond Well Forged, p. 1]

Maine Maritime Museum, just down the Kennebec River from BIW, is an outstanding resource for appreciating the State’s marine heritage. Nearby is the substantial Plant Memorial Home with apartments offering assisted and independent living options.

The former 1941 Colonial Style Central Maine Railroad Station on Commercial Street has been reused several times since its decommissioning in 1959, when passenger service to Bath was ended. (Historic American Building Survey photo)

World War I played an important role in the development of the city. At the outbreak of the War, shipbuilders quickly shifted production from merchant vessels to creating a military-merchant fleet. By 1916 the federal government provided over $3 billion (an enormous sum for the time). In 1917 the United State became active in the War, and by 1918 Bath shipbuilders were turning out destroyers and other vessels. See Portland’s Sagamore Village in World War II.

World War I played an important role in the development of the city. At the outbreak of the War, shipbuilders quickly shifted production from merchant vessels to creating a military-merchant fleet. By 1916 the federal government provided over $3 billion (an enormous sum for the time). In 1917 the United State became active in the War, and by 1918 Bath shipbuilders were turning out destroyers and other vessels. See Portland’s Sagamore Village in World War II.

All this work needed workers and workers needed housing. Bath’s population was reported by the 1910 U.S. Census as about 8,700; the 1920 Census reported it now as over 14,000. The “Emergency Fleet Corporation” was created to manage the construction of worker housing from a multi-million grant from the federal government by 1918. The City provided utilities for the project: streets, sidewalks, sewers. An early building was the Dikes Landing School.

Form of Government: Council-Manager

More Videos!

Additional resources

Armstrong, Michael and Alexis Judkins, Emily Love, and Otto Werwaiss. “The Railroad Station.” [undated] http://bath.mainememory.net/page/891/display.html (accessed December 13, 2017)

Baker, William Avery. A Maritime History of Bath, Maine and the Kennebec River Region. Bath, Me. Marine Research Society of Bath. 1973.

Banks, Ronald. Maine Becomes A State.

Pert, Perleston L. (Bub). “Bath’s World War I North End Brick Housing Project & Dike School.” The Times of Bath. November 2001. A publication of the Bath Historical Society.

“A Bond Well Forged: How Hyde School Began a 40-year-long Symbiotic Relationship with the City of Ships. “at http://www.hyde.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/a_bond_well_forged.pdf

Historic American Buildings Survey. (undated) photo: “Bath Railroad Station, 15 Commercial Street, Bath, Sagadahoc County, ME.” Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: HABS ME,12-BATH,11–2. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/me0301.photos.339134p/resource/ (accessed December 13, 2017)

*Photos, and edited text are from nominations to the National Register of Historic Places researched by Maine. Historic Preservation Commission.

Full text and photos are at https://npgallery.nps.gov/nrhp

Scontras, Charles A. Two Decades of Organized Labor and Labor Politics in Maine 1880-1900. Orono, Me. University of Maine. Bureau of Labor Education. 1969.

Varney, George J. A Gazetteer of the State of Maine. 1881. pp. 100-104.

National Register of Historic Places Bath > Listings