| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 5,690 |

| 1980 | 8,465 |

| 1990 | 9,818 |

| 2000 | 12,854 |

| 2010 | 12,529 |

| Geographic Data | |

|---|---|

| N. Latitude | 44:30:48 |

| W. Longitude | 69:26:08 |

| Maine House | District 3,4, |

| Maine Senate | District 35 |

| Congress | District 1 |

| Area sq. mi. | (total) 39.5 |

| Area sq. mi. | (land) 38.9 |

| Population/sqmi | (land) 228.2 |

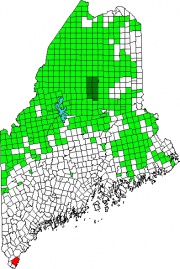

County: York

Total=land+water; Land=land only |

|

1787-1794 John Hancock Warehouse and Wharf (2018)

1787-1794 John Hancock Warehouse and Wharf (2018)

[YORK] The plantation of Agamenticus (or Acomenticus), now the town of York, was established on March 25, 1636 and incorporated as a city on April 10, 1641.

The name is from the Abnaki meaning “small river other side of island” or “on the other side of the river.”* A Native American returning from the sea would find what is now the York River as the smaller one on the other side of an island from the larger Piscataqua River.

Sir Fernando Gorges in 1641 immodestly named the capital city of his province Gorgeana.

York, was incorporated on November 22, 1652 from a portion of that city and is the second oldest town in Maine. The oldest is Kittery incorporated only two days earlier.

The following year the Old York Gaol was established as a prison, now the oldest English public building in the United States. In 1699 a court was established by Massachusetts to meet twice a year in York.

In 1692 it was the site of the Candlemas Ambush by Abenaki Indians in which 100 residents died in the French inspired incident. The battle was a severe blow to the English during what was known as King William’s War, or the first French and Indian War.

Here is how the 1881 A Gazetteer of Maine described the event:

In each of the three first Indian wars, great efforts were made by the savages to destroy the lace, but without success. The most disastrous of their attacks was in February, 1692, when an unexpected assault was made early in the morning by two or three hundred Indians under the command of Frenchmen. In half an hour, more than 150 of the inhabitants were either killed or captured. After burning all undefended houses on the north side of the river, the Indians retired quickly into the wilderness with about 100 prisoners, and all the booty they could carry. . . . Two garrison houses, McIntire’s and Junkin’s, built in this period were standing in the town, at a recent date.

Long a refuge for summer visitors seeking to enjoy its many beaches, York sought to protect their health in earlier times, as noted in the 1933 Report of the Health Department. The Long Beach area pictured below, with nearby Kendall Road, is one of these shore escapes. The view from Pebbledene illustrates the density of cottage development along the beach.

Sewall’s Bridge, built to carry the Organig Road over the York River in York in 1761, is a very old wood-piling bridge. The pilings were of different lengths, the length of each determined by probing the river bottom with a long pole tipped with a pointed piece of iron. The piles were driven into the river bottom by standing them upright, then dropping heavy oak logs on them.

The original bridge was so well built that it remained in use until 1934, when it was replaced with a wood pile bridge of a design very similar to that of the original. That replacement bridge is in regular use today. This bridge was dedicated as a historic civil engineering landmark on July 24, 1986.***

York was the home of widely acclaimed poet May Sarton. Most of the town’s inhabitants are located between U.S. Route 1 (inland) and U.S. Route 1A which runs along the coast. Its population has more than doubled in the past thirty years, and grew by nearly 31 percent between 1990 and 2000.

Form of Government: Town Meeting-Select Board-Manager.

More Videos!

Additional resources

*See Glossary, source number 7.

Bond, C. Lawrence. Native Names of New England Towns and Villages.

Banks, Charles Edward. History of York, Maine: Successively Known as Bristol (1632), Agamenticus (1641), Gorgeana (1642), and York (1652). Baltimore: Regional Pub. Co. 1967.

Bardwell, John D. The York Militia Company, 1642-1972. York, Me. The Author. 1972.

Catalogue of the Relics and Curiosities in the Old Gaol, York, Maine. 1903. Boston: Press of Joseph Dooley.

Emery, George Alexander. Ancient City of Georgeana and Modern Town of York (Maine) from its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time: also its beaches and summer resorts. Boston. G.A. Emery. 1894.

Ernst, George. New England Miniature: A History of York, Maine. Freeport, Me. Bond Wheelwright Co. c1961.

Fife, Hilda M. “Madam Woods ‘Recollections’.” Colby Library Quarterly. Series VII, No. 3 September 1965. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1824&context=cq (accessed June 23, 2013)

MacIver, Kenneth A. and William Thompson. York is Maine: Cape Neddick, York Village, Nubble Light. Cape Neddick, Me. Nor’East Publications. c1983.

***Maine Department of Transportation. “Sewall’s Bridge, York, Maine.” http://maine.gov/mdot/historicbridges/otherbridges/sewallsbridge/index.shtml (accessed December 14, 2017)

Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. Augusta, Me. Text and photo from National Register of Historic Places.

Marshall, Edward Walker. Old York, Proud Symbol of Colonial Maine, 1652-1952. New York. Newcomen Society in North America. 1952.

Masterton, Robert C. That York Harbor Bridge: only a small structure, but it has disrupted a town, embarrassed a state, roused the government and threatens to embroil the next Republican National Convention. New York. Eastern Publishing Co. 1910.

Moody, Edward C. Handbook History of the Town of York, from Early Times to the Present. Augusta, Me. York Pub. Co. 1914.

Olivier, Julien. Prendre le large: Big Jim Cote pêcheur. Bedford, N.H. National Materials Development Center for French. 1981.

Roberts, Kenneth. Boon Island. New York: Doubleday, 1956, c1966.

Rolde, Neil. York is Living History. Brunswick, Me. Harpswell Press. 1975.

“Sewall’s Bridge (c. 1908)” photo. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016813921/ (accessed December 14, 2017)

Spiller, Virginia S. Ed. 350 years as York: Focusing on the 20th Century. Town of York, 350th Committee. 2001.

Sylvester, Herbert Milton. Old York. Boston. W.B. Clarke Co. 1909.

Varney, George J. A Gazetteer of the State of Maine. p. 608

Vietze, Andrew and Stephen Erickson. Boon Island : a true story of mutiny, shipwreck, and cannibalism. Guilford, Conn., Globe Pequot Press, 2012.

York Tercentenary Committee (Me.) Three Hundredth Anniversary, 1652-1952: Town of York, Maine. York, Me.? The Committee. 1952.

York, Maine Then and Now: A Pictorial Documentation. York, Me. The Old Gaol Museum Committee and the Old York Historical and Improvement Society. 1976.

National Register of Historic Places – Listings

Barrell Homestead

[west of York Corner on Beech Ridge Road, York Corner] In 1976 the house, built about 1720, was still owned by descendants of Jonathan Sayward who acquired the it in 1758. Built about 1720 by Matthew Grover, Jonathan Sayward acquired the house in 1758. Sayward was a justice of the peace and the wealthiest merchant in York. His daughter Sally, in 1758, married Nathaniel Barrell, a colorful and eccentric figure, at the time a Portsmouth, New Hampshire businessman. A year later Barrell served as a lieutenant in British General Wolfe’s army on the Plains of Abraham near Quebec during the “French and Indian War”. The next year, 1760, he sailed for England where he spent the next three years. He apparently gained favor from King George III, since he then served for three years on Governor Wentworth’s council for New Hampshire.

[west of York Corner on Beech Ridge Road, York Corner] In 1976 the house, built about 1720, was still owned by descendants of Jonathan Sayward who acquired the it in 1758. Built about 1720 by Matthew Grover, Jonathan Sayward acquired the house in 1758. Sayward was a justice of the peace and the wealthiest merchant in York. His daughter Sally, in 1758, married Nathaniel Barrell, a colorful and eccentric figure, at the time a Portsmouth, New Hampshire businessman. A year later Barrell served as a lieutenant in British General Wolfe’s army on the Plains of Abraham near Quebec during the “French and Indian War”. The next year, 1760, he sailed for England where he spent the next three years. He apparently gained favor from King George III, since he then served for three years on Governor Wentworth’s council for New Hampshire.

In 1764, Barrell adopted the Sandemanian doctrine, preached by Reverend Robert Sandeman, a disciple of Reverend John Glass and the “Glassites” in England. His zealous enthusiasm made him openly critical of other clergymen, making enemies among influential citizens. In 1765, as repercussions of the Stamp Act were felt in Portsmouth, Barrell refused to join the opposition. Labeled by some as a Tory, his business dwindled and he moved to his father-in-law’s farm on Beech Ridge in York. Barrell’s obsession with the Sandemanian doctrine was a source of friction between him and his wife’s father. Barrell refused to permit his children to visit their grandfather, a pillar of the First Parish Church.

Sayward had as heir to his extensive business interests only one child, a daughter married to a man who had failed as a merchant, denied him the right to know his grandchildren and whose “temper is very short and his conversation insupportable”. Sayward had, along with his son-in-law, come under suspicion as a Tory and was stripped of all his public offices.

In 1787 Nathaniel Barrell, in his fiery opposition to the proposed federal constitution, reflected the sentiments of the majority of York voters and was chosen as one of two delegates to the ratifying convention in Boston. Once in the city, in the presence of such giants as Samuel Adams and John Hancock, his judgement in the matter was swayed. The Convention of 365 delegates voted for ratification by a slight majority of 19, of which Barrell was one. Now unpopular in York, he spent the remainder of his years at what was now called “Barrell Grove”.

Distrusting his son-in-law’s impulsive nature, Jonathan Sayward bequeathed Barrell Grove to his daughter and then to Nathaniel’s son John. His business interests went to another grandson. To Nathaniel he left “a decent suit of apparell for every part of his Body and the walking stick he gave me”. Sarah Barrell, wife of Nathaniel, died in 1805. Her oldest child, now an adult, was Sally Sayward Barrell, “Madam Wood”, (see Fife reference above) who gained fame as Maine’s first professional female novelist, publishing works of considerable popularity including: “Julia, or the Illuminated Baron”, “Dorval, or the Speculator”, and “Amelia or the Influence of Virtue”. Nathaniel Barrell, after devoting his later years largely to farming, was buried in the family plot at Barrell Grove. He died in 1831 on the eve of his 99th birthday.

In 1841, the house, rich in its historical associations, was altered from its original two-story, hip roofed form into the present massive three-story gable roof structure with an extensive ell. [Frank A. Beard photo, 1976]

Boon Island Light Station

[Boon Island] The Boon Island Light Station towers above this small rock island located approximately six miles off the Maine coast. It contains the tallest light tower in Maine and is the southernmost of the seacoast lights. The Light Station was established during the War of 1812, and is the seventh oldest station in Maine. In the 1850s, when a comprehensive classification of lights was instituted, Boon Island was ranked as a primary seacoast station, one of only six such lights in Maine in 1861. Widely spaced along the coast, these stations were crucial navigational aid in the major shipping lanes linking Maine to Europe and other United States ports. In 1978 this station was automated by the Coast Guard, and many of its outbuildings were removed.

[Boon Island] The Boon Island Light Station towers above this small rock island located approximately six miles off the Maine coast. It contains the tallest light tower in Maine and is the southernmost of the seacoast lights. The Light Station was established during the War of 1812, and is the seventh oldest station in Maine. In the 1850s, when a comprehensive classification of lights was instituted, Boon Island was ranked as a primary seacoast station, one of only six such lights in Maine in 1861. Widely spaced along the coast, these stations were crucial navigational aid in the major shipping lanes linking Maine to Europe and other United States ports. In 1978 this station was automated by the Coast Guard, and many of its outbuildings were removed.

The light tower at Boon Island is the third such structure on the site. The original tower was destroyed in 1831, later rebuilt and then finally replaced by the present granite tower. This station has a distinctive character that illustrates an unusual example of mid-19th century light station design and construction.* [Kirk F. Mohney photo, 1987]

Boon Island is famous for what one author called “a true story of mutiny, shipwreck, and cannibalism.” (See references above: Vietze and Roberts.)

Brave Boat Harbor

[110 Raynes Neck Road] Brave Boat Harbor Farm is a small historic district on the coast that is notable for its designed landscapes and architecture. The farm was the home of Marion and Calvin Hosmer, Jr. In 1951 they built stately buildings that include a stone-veneered Georgian style manor house and a complex of neo- Federalstyle barns, fields, pastures and agricultural outbuildings. Complementing this are the gardens and landscapes designed by Marion Hosmer, including the formal walled front garden, arborvitae enclosed orchard, fruit trees, and naturalistic paths that lead through ancient lilacs to an old burying ground or scenic views of the shore.

[110 Raynes Neck Road] Brave Boat Harbor Farm is a small historic district on the coast that is notable for its designed landscapes and architecture. The farm was the home of Marion and Calvin Hosmer, Jr. In 1951 they built stately buildings that include a stone-veneered Georgian style manor house and a complex of neo- Federalstyle barns, fields, pastures and agricultural outbuildings. Complementing this are the gardens and landscapes designed by Marion Hosmer, including the formal walled front garden, arborvitae enclosed orchard, fruit trees, and naturalistic paths that lead through ancient lilacs to an old burying ground or scenic views of the shore.

The property has high artistic value, and embodies the distinctive characteristics of the Colonialrevival at mid-20th century. Calvin and Marion both grew up in the southeast Massachusetts town of Sharon. They married in 1928 and lived in a rural neighborhood there. By the mid 1930s they felt the area was becoming overdeveloped and after 12 years of looking they found a 150 acre parcel on the north edge of Brave Boat Harbor on Raynes Neck. Granted to Francis and Eleanor Raynes in 1638, the property had been occupied continuously by that family until 1910. When the Hosmer’s purchased the land all that remained was a relatively new (about 1939) summer cottage, an old cellar hole, burying ground, collapsed stone walls, and a mammoth lilac hedge. The land had been essentially deforested and the fields were overgrown.

The property has high artistic value, and embodies the distinctive characteristics of the Colonialrevival at mid-20th century. Calvin and Marion both grew up in the southeast Massachusetts town of Sharon. They married in 1928 and lived in a rural neighborhood there. By the mid 1930s they felt the area was becoming overdeveloped and after 12 years of looking they found a 150 acre parcel on the north edge of Brave Boat Harbor on Raynes Neck. Granted to Francis and Eleanor Raynes in 1638, the property had been occupied continuously by that family until 1910. When the Hosmer’s purchased the land all that remained was a relatively new (about 1939) summer cottage, an old cellar hole, burying ground, collapsed stone walls, and a mammoth lilac hedge. The land had been essentially deforested and the fields were overgrown.

After testing the seasonal waters for several years, the Hosmers relocated to Maine in 1951. Brave Boat Harbor Farm is an intimate, yet regal Gentlemen’s Farm built essentially between 1951 and 1954, with a few additional agricultural outbuildings completed in the 1960s. The buildings and gardens of the Farm were consciously modeled from historic precedents: the house is Georgian in style, two of the barns utilize Federal-era details, and the gardens draw on English examples.

At all levels, this property can be seen as the work of its owners. Calvin Hosmer’s occupation was as a partner in his father’s flour brokerage firm in Boston, but his avocations included architecture, farming, blacksmithing, bargain hunting (he collected back lots of reproduction colonial-era hardware during the Depression), and he was an avid horseman. He died in 1996.

After Marion’s death in 1997 her gardens were documented for the Garden Club of America Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. The significance of this property comes from the extent to which the buildings and grounds so masterfully complement both each other and the natural landscape, while also strongly evoking historic precedents. It is also a well designed and executed mid-20 century example of the continuing allure of the Colonialrevival in Maine.* [Christi A. Mitchell photos, 2007]

After Marion’s death in 1997 her gardens were documented for the Garden Club of America Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. The significance of this property comes from the extent to which the buildings and grounds so masterfully complement both each other and the natural landscape, while also strongly evoking historic precedents. It is also a well designed and executed mid-20 century example of the continuing allure of the Colonialrevival in Maine.* [Christi A. Mitchell photos, 2007]

Breckinridge, Isabella, House

[off U.S. 1] The Isabella Breckinridge House (or “River House”) is among the early 20th century summer estates in York County. Large Villas like this appear only occasionally in Maine outside of Mt. Desert Island. The Brecknridge House is particularly rare, incorporating Colonialrevival features into an Italian villa plan. The house was built in 1905 and combined a Mediterranean villa configuration with a mansard roofed main portion. Guy Lowell was a prominent East Coast architect and designed a number of Bar Harbor villas, most notably Eegonos, the Mediterranean Beaux-Arts palace of Walter G. Ladd.

Gutted by fire in the mid-1920’s, its charred brick walls were painted white and the interior reconstructed in 1927. The exterior of the central portion was somewhat altered, a neo-Georgian gambrel roof with Dutch straight-edged gables replacing the mansard. It is not known whether Lowell was architect for the remodeling (1927 was the year of his death).

Gutted by fire in the mid-1920’s, its charred brick walls were painted white and the interior reconstructed in 1927. The exterior of the central portion was somewhat altered, a neo-Georgian gambrel roof with Dutch straight-edged gables replacing the mansard. It is not known whether Lowell was architect for the remodeling (1927 was the year of his death).

Mrs. Isabella Goodrich Breckinridge was the daughter of B. F. Goodrich, the rubber magnate. Her husband, John Cabell Breckinridge, III, was the son of the noted Kentucky senator, Confederal General and Secretary of War, Presidential candidate, and U. S. Vice President of the same name. The house passed through the female line of succession to Mrs. Mary Patterson who donated it to Bowdoin College reserving residential rights. [Frank A. Beard photos, 1983]

Cape Neddick Light Station

[Cape Neddick] Cape Neddick Light Station, on a high promontory reaching out into the Atlantic between Portsmouth and Portland, is an important navigation mark guiding sailors away from the jagged rocks at its base. One of the few stations that has never been rebuilt, it has become a mecca for artists and tourists because of its picturesque location and accessibility from the mainland. Locally known as “The Nubble”, it is connected by a bar with the mainland at a very low of tide.

There are five buildings on the island: the keeper’s house, which is connected with the light tower by a covered way; the red brick oil house; the wood frame workshop; and the boat house with ways leading to the water. The 39 foot light tower is iron lined with brick. The lantern has eight panes of glass, four ruby colored facing the land and the remainder, white, exposed to the ocean. [See photo above.]

Conant–Sawyer Cottage

[14 Kendall Road] Built in 1877, enlarged in 1896, and moved about 1909, the Conant-Sawyer cottage is a Second Empire style summer house overlooking York Beach from Dover Bluffs. It stands out amidst its much altered neighbors, thereby conveying an accurate image of the modest cottages that characterized the immediate post-Civil War development of Maine’s summer colonies.

Dr. Josiah Conant of Somersworth, New Hampshire, bought the house shortly after its completion and owned it until his death. His widow sold the cottage to its most historically significant owner, Charles Henry Sawyer. A Dover woolen manufacturer, Sawyer was elected Governor of New Hampshire in 1886.

Sawyer apparently added the wing now containing the kitchen in 1896. The cottage stands in an area of modest summer residences known as Concordville which, as one turn-of-the-century publication noted, was “occupied almost wholly by New Hampshire people.” This illustrates the pattern in which visitors from small Maine or New Hampshire cities tended to congregate with other hometown vacationers. An 1872 map shows the handful of buildings in the neighborhood. An 1888 birds-eye-view reveals a much enlarged colony adjoining two roads that followed the peninsula’s shore. To the north a pair of expansive hotels indicated the explosive growth of the local tourism industry.

Hancock, John, Warehouse

[Lindsay Road] John Hancock is better known for his political involvement than for his trading activities; nevertheless he was the holder of a vast fortune by the age of twenty-seven due to his being the heir to his merchant uncle’s fortune. Hancock never showed any great talent for trade and at the encouragement of Samuel Adams was soon much more involved in politics than in commerce.

For all practical purposes, cash was non-existent during the post Revolutionary era; bartering was common. Items of merchandise were whalebone and oil, molasses, cured fish, tar, leather, bales of salt, and coal were exchanged for the commodities of rich fabrics, buckles, and swords, hourglasses, rum wine, tea and ornate furniture.

Among those products, not surprisingly, rum had the quickest turnover. John Hancock had warehouses and wharves along the entire coast, along with a number of ships to transport his goods. His investments in Maine, however, did not appear to very lucrative. He inherited from his Uncle Thomas fifty acres of vast timber tracts in Maine which failed to appreciate materially.

He also owned a small business in the remote little town of York in the form of a wharf, store and storehouse, that were situated just south of Sewall’s Bridge on the York River. He only owned one half of the warehouse, which he shared with Joseph Tucker. After Hancock’s death, the heir, his brother Ebenezer sold his share of the warehouse to Tucker. It is uncertain whether Hancock visited Maine. [State Park & Recreation Commission photos, 1966]

He also owned a small business in the remote little town of York in the form of a wharf, store and storehouse, that were situated just south of Sewall’s Bridge on the York River. He only owned one half of the warehouse, which he shared with Joseph Tucker. After Hancock’s death, the heir, his brother Ebenezer sold his share of the warehouse to Tucker. It is uncertain whether Hancock visited Maine. [State Park & Recreation Commission photos, 1966]

Hawkes Pharmacy

[7 Main Street] Hawkes Pharmacy is an architecturally significant example of the Tudor Revival style, and one of only two historic commercial buildings in the York Beach business district that has not been significantly altered.

[7 Main Street] Hawkes Pharmacy is an architecturally significant example of the Tudor Revival style, and one of only two historic commercial buildings in the York Beach business district that has not been significantly altered.

Built in 1902 by Dr. Wilson Hawkes, it was built at a time when the York Beach area was prospering as one of the major summer resorts on the Maine coast. That prosperity is evident in the unusual attention given to ornamental features for this small commercial building.

York historically has two major concentrations of summer colony architecture: York Harbor where the summer homes were built by the most wealthy visitors, and York Beach where houses belonged to people of more moderate means. Each community also had its own commerical district. York Beach contained a number of hotels and commercial establishments oriented toward summer resort entertainment. The Hawkes Pharmacy occupied a prominent location in the center of this small summer community. Dr. Wilson Hawkes established a practice in York Harbor in 1872. His arrival from western Maine coincided with the early development of this community as a summer resort.

After acquiring an old mansion, he built a pharmacy and art studio in the harbor to serve the wealthy summer visitors. In 1899, Dr. Hawkes purchased the York Beach pharmacy of L.K.Mead & Co. His son Ralph, who was about to graduate from Dartmouth, took over the management of the new buisiness. The success of the York Beach pharmacy enabled father and son to purchase a lot opposite the Atlantic House hotel and erect a new building. In October, 1901, they hired local architect Fred C. Watson to design the building, which was to contain two stores. One half of the store was the Hawkes Pharmacy operated by son Ralph. The other half was leased to D.H.Stacy & Son, a dry goods merchant, who lived on the second floor. Hawkes operated a pharmacy here until the 1940s. A fire at about that time did major damage to the interior. While the surrounding buildings have either been destroyed or undergone major alterations with non-historic materials, this building survived with its major exterior features intact. Hawkes Pharmacy was extensively renovated in 1990, including the construction of missing features on the principal facade. The ground floor continues to be used for shops.* [Roger G. Reed photos, 1993]

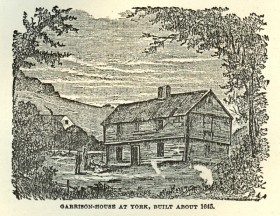

McIntire Garrison House, National Historic Landmark

[Maine Route 91 about 5 miles West of York] The Mclntire Garrison is the most notable example remaining in Maine of a regional type of seventeenth century structure known as a garrison house, and built of sawn logs. It is probably the most significant type of characteristically 17th century types which were once relatively common. (Charles Snell photo)

The use of the type persisted because of its defensive advantages in an area where Indian raids were common until sometime in the eighteenth century. The house has traditionally been dated around 1645, making it one of the oldest log buildings in the country, although recent investigation shows its construction date more likely about 1707. The essence of this log building is hidden behind more recent clapboarding, which makes the building appear undistinguished from a number of other eighteenth century New England overhang type houses in the area.

Moody Homestead

[Ridge Road] The Moody Homestead is a substantial reminder of the Moody Family in Maine, a family closely identified with notable episodes on the political, literary and educational heritage of New England. In York, one of the oldest English outposts in America, it is on the venerable Post Road. Although the main block was built by Joseph Moody in 1790, its rear ell preserves a structure of perhaps a century earlier. This original building was built by a Stonemason and sold, along with considerable acreage, to Moody in the 1770s. Joseph Moody was the second son of “handkerchief” Moody (1700-53) and the grandson of Rev. Samuel Moody (1675-1747). Samuel Moody, a native of Massachusetts, and a 1697 graduate of Harvard College came to York in 1698 with an appointment as chaplain to the garrison and settlers who were recovering from the devastating Indian raid of 1692. He stayed for almost fifty years, being ordained and heading York’s first parish when it was organized in 1700.

The Reverend Samuel Moody was an enthusiastic successor to the tradition of New England Puritanism espoused by his teacher Cotton Mather. He was an eloquent preacher. Moody served with gusto as chaplain of the Louisburg Expedition of 1745 headed by his brother-in-law, Sir. William Pepperell. He was also a greatgreat-grandfather of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The builder of the Homestead, Joseph, assisted his brother Samuel who was the first Preceptor of Dummer Academy in Byfield, Massachusetts, for many years. Concurrently Joseph was buying up property in York to which he retired and raised the existing house in 1790. Tradition maintains that it was inspired by the Dummer Mansion in Byfield, one of the earliest Georgian structures in New England. [John Bardwell photos, 1974]

Old Schoolhouse

[York Street (on the Village Green)] In 1746, the residents of York Corner requested and were granted permission to build a schoolhouse twenty rods from the Lewis Bane House at the corner. The corner residents were to build it at their own costs and charges. The house contained only the bare necessities, including a fireplace, and in 1755 two pounds, thirteen shillings, three pence was paid by the town to finish the schoolhouse.

This is one of the earliest existing 18th century schoolhouses in New England and provides an example of typical school life in the early years. It is currently a museum with figures in authentic costumes, including the schoolmaster, boys, girls, and an Indian boy.

Old York Gaol

[4 Lindsey Road] The Old Gaol is a well preserved and rare example of a substantial colonial prison building. Built in four building programs between 1720 and 1806, the structure has been altered very little and clearly illustrates the atmosphere of a type of building few people see, particularly the interior.

Begun about 1720, the Old Gaol served its incarceration function for over a century-and-a-half, until at least 1879. Although not the first gaol in Maine, it served all of the Province until 1760, and continued to serve the town for another century.

Altering its function to some degree at least, the building served as a schoolhouse during the 1890’s. In 1900, at the instigation of William Dean Howells, came to be used as a museum when a long term lease was obtained by the Gaol Committee of the Old York Improvement Society and The Society for the Preservation of Historic Landmarks. The Gaol is still administered by the committee, which keeps it well maintained and regularly open to the public. [See photos in video above]

Pebbledene

[99 Freeman Street, York Beach] The 1896 Queen Anne style “Pebbledene” is architecturally significant as the last major intact example of a turn-of-the-20th century summer cottage in the Evanston area of York Beach. In a neighborhood containing a high concentration of summer cottages from a variety of periods, it is the last unaltered 19th century structure of this size here. Although larger and more ornate cottages were built elsewhere in York, this house represents the type built by upper middles class visitors to York Beach, who were also major contributors to the development of the summer resort.

The Edwin Rogers family summered at York Beach as early as 1893. It was one of the major coastal resort areas where most hotels and smaller cottages were built. Although the views were no less spectacular from York Beach, a social stratification generally distinguished it from York Harbor where wealthy summer visitors built the largest cottages.

The Rogers Cottage was one of the largest and most architecturally distinguished cottages to be built in York Beach. They named it “Pebbledene” after the large number of small pebbles on the beach nearby. With its wide veranda, corner tower and second floor porch, “Pebbledene” features all the elements that went into the design of a substantial summer cottage of the period.

Rose, Robert, Tavern

[off Long Sands Road] Robert Rose’s tavern in York is a rare example of a pre-Revolutionary hostelry in Maine. It had its origin as the 17th century home of John Banks. Banks was the son of Richard Banks, one of four Englishmen who came to York in 1642 from Scituate, Massachusetts, to settle on adjoining land grants. On the ocean at Long Sands, north of York Village, these lots became known as Scituate Men’s Row. John Banks was born in York in 1657 and built his home on the Row in 1680. Land at Long Sands had become available for ownership after Massachusetts disavowed the rights of the patentees and gave possession of the claims to the town. Then one citizen after another applied for and received grants. Richard Banks, John’s father, who had become active in the public affairs of York, was slain in the Indian Massacre of January 25, 1692, along with two of his sons.

Two other sons, Joseph and John Banks, survived. The latter’s house was spared because the Indians apparently moved along the beach at Long Sands, missing a few dwellings that stood approximately 1000 feet inland from it. Banks lived until 1723-24, serving several terms as a selectman of the town. Robert Rose acquired John Banks’ property in 1756 and extensively remodeled his 17th century house into a substantial two story hipped roof tavern of forthright Colonial design. Rose maintained a hostelry here from 1759 to 1762, periodically hosting meetings of the town selectmen. In addition, he was a skilled peruke or periwig maker and maintained a barber shop in front of the jail at York Village.

He further supplemented his income as underkeeper of the prison and as a master of the House of Correction. Robert Rose’s tavern is of importance to York, one of Maine’s first towns, for its connection with its early settlers, the Banks family. Moreover, the building is of statewide significance as one of Maine’s few Revolutionary War period inns. [John Bardwell photo, 1974)

Sedgley, John, Homestead

[north of York Corner on Chases Pond Road, York Corner] Having been restored with great care, the two houses and various outbuildings of the John Sedgley homestead are particularly fine examples an early 18th century farmstead in southern Maine. In a still largely unspoiled area, they present an appearance little changed during the 250 years of their existence. John Sedgley, born in England between 1680 and 1690 and a turner by trade, came to York as a young man. He married Elizabeth Adams in 1714, the seventh child of Thomas and Hannah Adams. They were a prominent York family related to the famous Adams’s of Quincy, Massachusetts. The lot upon which the homestead stands was given to the young couple by Thomas Adams in 1715. In the same year they built the five-room Cape Cod house which became their first home.

Within about five years a growing family required larger quarters and Sedgley built the six-room two-story dwelling closely adjoining. The older house probably became a residence in due time for the oldest son, John Sedgley II. Adams in January and December of 1716 added two more lots to the Sedgley holdings. By middle life Adams, in addition to his trade as a turner, had become a respected and prosperous landholder in York. Although not a leader in community affairs himself, his son was elected Surveyor of Highways in 1775. Since the Town of York, one of the earliest settlements in Maine, was almost completely wiped out by the great Indian raid of 1692, the John Sedgley Homestead presents one of the best and most substantial examples of the new settlement that sprang up and formed the foundation of the community. [Ernest Brennerman photos, 1975]

St. Peter’s By-The-Sea Protestant Episcopal Church

[529 Shore Road, Cape Neddick] The 1898 St. Peter’s By-The- Sea Protestant Episcopal Church is a Gothic style stone and wood building designed in the manner of an English country chapel. According to local historians, Philadelphia lawyer George Meecum Conarroe and his wife Nannie first summered in Cape Neddick in 1889. The following year they built a stone summer house on a site near the church site. Tradition holds that Mr. Conarroe had expressed a desire to erect a church on Christian Hill so the cross would be visible to sailors as they approached Perkins Cove in Ogunquit. After his death in 1896, Mrs. Conarroe built the church (as well as the Ogunquit Memorial Library) in memory of her husband.

York Cliffs Historic District

[Agamenticus Avenue] Scattered with generous grounds over a beautiful 25 acre seashore property are eight of the large summer houses of the original thirteen built at York Cliffs. Built (with one exception) between 1892 and 1901, these large houses clearly represent the kind of affluence which was lavished upon selected and exclusive enclaves along the Maine coast at the turn of the century. All but two were built in the then popular Shingle Style calculated to blend comfortably into the coastal landscape.

The eight houses here present one of the best examples along the Maine coast of exclusive land development by companies catering to the wealthy who wished to participate in the new trend toward summer living by the sea. An extensive brochure published by the York Cliffs Improvement Company correctly describes its land holdings as an area “which is rapidly gaining prestige as an exclusive and aristocratic resort combining all the qualities which form an attractive and desirable summer home.”

In addition to the sale of land, the company offered a spring fed water supply and sewerage disposal facilities. A golf course and stables were also available. It should be noted that when originally built, these houses had an unobstructed view of the ocean over open fields since grown up. As in the case of other similar developments, the company early on built a fine hotel on the property to attract people to the area who might become future land purchasers. Later it served as a place of entertainment for the cottagers and their guests. The land deeds issued by the company contained a number of restrictions designed to protect each land holder and thus make acquisition more attractive. These included a standard of cost and architectural excellence for each cottage erected. Here represented is an era of relaxed affluence and vacation comfort, seldom encountered in today’s frantic search for summer recreation.

In addition to the sale of land, the company offered a spring fed water supply and sewerage disposal facilities. A golf course and stables were also available. It should be noted that when originally built, these houses had an unobstructed view of the ocean over open fields since grown up. As in the case of other similar developments, the company early on built a fine hotel on the property to attract people to the area who might become future land purchasers. Later it served as a place of entertainment for the cottagers and their guests. The land deeds issued by the company contained a number of restrictions designed to protect each land holder and thus make acquisition more attractive. These included a standard of cost and architectural excellence for each cottage erected. Here represented is an era of relaxed affluence and vacation comfort, seldom encountered in today’s frantic search for summer recreation.

York Historic District

[roughly US Route 1, US Route 1A, Maine Route 103 and Woodbridge Road] The significance of the Town of York could rest upon its history alone, not only its importance to the state of Maine, but the early history of York is the early history of this nation. York, especially York Village and York Harbor, remains in essentially as they were in the 18th and 19thcenturies.

Architecturally York is a surviving late 17th and 18th century town. Its buildings are not great mansions but homes of this country’s pioneers. The homes and the public buildings are in a fine state of preservation because of the local people who realize their proud history and the contributions of their ancestors to the America’s history.

The District contains 56 historic buildings, including the Episcopal Stone Church, Old Gaol, Old Schoolhouse, York Town Hall, Powder House, York Public Library, among others. (see video above)