Historically

Lobsters, now a major factor in Maine’s commercial fisheries, were once so plentiful that Native Americans used them to fertilize fields and to bait fish hooks. According to Colin Woodward, in 1608 with the Popham Colony failing,

Lobsters were everywhere. On their way to the Kennebec, Raleigh Gilbert’s men caught fifty lobsters “of great bigness” by simply rowing a boat over shallow water and gaffing the unsuspecting lobsters with a boat hook as they were spotted along the bottom. But there was no way to transport them back to he markets of Europe. Lobsters begin to putrefy almost immediately after death, they can’t be salted or dried, and nobody yet knew how to keep them alive for more than a few days. Lobsters were a good fresh snack, but useless for trans-Atlantic commerce.

In colonial times, they were considered “poverty food.” They were harvested from tidal pools by hand and served to children, prisoners, and indentured servants.

Seagulls swarm around a lobster boat at Halfway Rock in Casco Bay, hoping for fish meal bait leftovers. The other boat is rigged for lobstering and fishing for other species.

The trap fishery emerged around 1850 and now Maine is the largest lobster-producing state. Though the number of lobstermen has increased dramatically, the size of the catch had remained relatively steady. In 1892, 2600 people in the Maine lobster fishery caught 7,983 metric tons; in 1989, 6300 Maine lobstermen landed 10,600 metric tons. But more recently, the catch amount has exploded. Along the coast, the catch varies in different locations with different conditions.

Governor Kenneth M. Curtis, Maine First Lady Polly Curtis, and U.S. First Lady Ladybird Johnson, assisted by actor and Maine resident Gary Merrill (c. 1967)

No longer the “junk food” of the earlier centuries, the tourism industry has capitalized on the beast as a rare treat. Politicians of all persuasions are happy to pose with a lobster when the occasion presents itself.

See an amateur film (circa 1980) of a lobster festival on the offshore island community of Frenchboro.

The Process

Lobster buoys are attached to lines leading to, usually, a string of traps. Each fisherman’s buoys have a unique design and combination of colors distinguishing them from those of others in the area.

The first lobster pound appeared on Vinalhaven island in 1875 and others quickly followed. Lobsters are kept in tanks (pounds) with water passing freely through them so dealers can wait for the price to increase or allow a newly-molted lobster time to harden its shell.

Lobsters shed their shells as they grow. In this “molting” process, the shell splits and the lobster beneath backs out. It will then hide among rocks and in other protected areas for 6-8 weeks until the new shell hardens. After 4 to 5 molts per year for several years, a lobster reaches its legal fishing size.

Any egg-bearing females must be released. Some female lobsters are voluntarily “V-notched,” that is, a triangular slice is cut from a tail flipper. This conservation technique is meant to keep them off the dinner table and in the breeding pool. 15 – 20% of legal lobsters are released in Maine because they are V-notched females. Many more are released because they are either too small or too big.

Maine lobster fishers have traditionally protected their share of the resource through lobstering territories. In any port, they have an informal, often unspoken agreement about where each member of the fishing community may lay his traps. All the members of one community even lay their strings of traps in one direction, such as north to south, so they don’t tangle their lines in someone else’s gear.

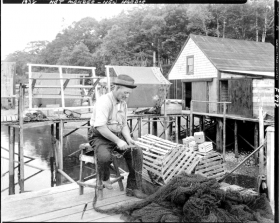

Until recently, lobster traps were made of wooden slats, as shown in the photo above. Now more stackable and more durable rectangular wire traps have virtually replaced the older models. People seeking to enter lobster fishing usually start with a few traps or work as a “sternman,” baiting traps and carting gear, for an established fishermen. Eventually, he or she will be allowed to take over his or her own territory. Those who do not follow this initiation will not be welcome among local fishermen and are likely to have their gear sabotaged.

The Uncertain Future

Lobster abundance in Maine is currently at record levels according to a recent (2009) stock assessment. Maine landings averaged approximately 20 million pounds from 1950 to 1990, but have increase to over 100 million pounds in 2011.

Lobster is managed in Maine waters through a co-management process, and regionally by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), and or federally by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The coast-wide lobster stock is assessed every five years. The last assessment determined that stock in the Gulf of Maine was not over fished nor was overfishing taking place. However, catch rates in the Gulf of Maine are approaching a level that would trigger consideration of additional restrictions on the fishery.

Minor decreases in marketable lobster could hurt a large number of coastal communities, so there is cause for concern on the future status of the stock. A new coast-wide assessment will be compiled in 2014 by the ASMFC.

During the period 1950 to 1990, traps set per year increased from 430,000 in 1950 to 2,605,000 in 1996. Since 1997 there has been an additional 25% increase in traps, which now total in excess of 3 million traps allocated to 5,977 fishers. The average age of a Maine lobsterman in 2008 was is 46.7 with a median age of 48. Maine instituted limited entry in all areas, with the exception of one, so in essence there is now a cap on the total number of traps that can be set in State waters.

The Maine lobster fishery has been experiencing unprecedented landings in recent years. If past history is any indication, it is unrealistic to assume that this condition will continue indefinitely.

Additional resources

Acheson, James. Changes in the Territorial System of the Maine Lobster Industry. Orono, Me. University of Maine Sea Grant College Program. 2003. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Beaupain, Dean A. The Maine Lobster: Problems and Proposed Remedies. 1976. (INDEPENDENT WRITING PROJECT (J.D.)–University of Maine School of Law, 1976.)

Corson, Trevor. The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite Crustacean. Harper Perennial. New York. 2005. (Excellent!)

Dow, Robert L. A Study of Major Factors of Maine Lobster Production Fluctuations. Augusta, Me. Maine Department of Sea and Shore Fisheries. 1967. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Maine Department of Marine Resources. A Guide to Lobstering in Maine. Augusta, Me. 2005. http://www.maine.gov/dmr/rm/lobster/guide/

Maine Department of Marine Resources. Program Review Committee. Program Review of The Maine Department of Marine Resources. Augusta, Maine. September 2, 2011. http://www.maine.gov/dmr/news/dmrreview9-2-11.pdf. (accessed November 28, 29011) Text in “The Uncertain Future” section is take from the Review, p. 40, condensed and partially rewritten to be accessible to the non-professional audience.

Taylor, David, collector. [Maine lobsterman interview], Fall 1974. (Cataloger Note: Independent collection of folklore material, contributed to the Archives. Audiotape reference number is T867. Contains interview with Sherm Stanley, Jr. about lobster fishing, types of boats, gear, costs, traps, co-ops, laws, etc. (Life of the Maine Lobsterman Project.) Materials located in: Northeast Archives of Folklore and Oral History, Maine Folklife Center, University of Maine, Orono.

Wahle, Richard A. Recruitment, Habitat Selection, and the Impact of Predators on the Early Benthic Phase of the American Lobster. Orono, Me. 1990. (Thesis (Ph.D.) in Zoology–University of Maine, 1990.) [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Woodward, Colin. The Lobster Coast. p. 81