Pemaquid Point Light (2001)

Portland Head Light (2001)

West Quoddy Head Light on Passamaquoddy Bay (1999)

Major Lighthouses Along the Coast

___

Baxter Island Light

(1828) Cranberry Isles

Bass Harbor Head Light

(1858) Tremont

Bear Island Light

(1839) Cranberry Isles

Boon Island Light

(1811) York

Browns Head Light

(1832) Vinalhaven

Burnt Coat Harbor Light

(1872) Swans Island

Burnt Island Light

(1821) Southport

Cape Elizabeth Light

(1829) Cape Elizabeth

Cape Neddick Light

(1879) York

The Cuckolds

(1892) Southport

Curtis Island Light

(1838) Camden

Dice Head Light

(1829) Castine

Doubling Point Light

(1899) Arrowsic

Eagle Island Light

(1838) Deer Isle

Egg Rock Light (1875)

Winter Harbor

Fort Point Light

(1836) Stockton Springs

Franklin Island Light

(1805) Friendship

Goat Island Light

(1835) Kennebunkport

Goose Rocks Light

(1890) North Haven

Great Duck Island Light

(1890) Frenchboro

Grindel Point Light

(1850) Islesboro

Halfway Rock Light

(1871) Casco Bay

Hendricks Head Light

(1829) Southport

Indian Island Light

(1850) Rockport

Discontinued 1934, private

Isle au Haut Light

(1907) Isle au Haut

Libby Island Light

(1817) Machiasport

Little River Light

(1847) Cutler

Lubec Channel Light

(1890) Lubec

Manana Island Fog Signal Station Light

(1875) Monhegan

Mark Island Light

(1857) Stonington

Marshall Point Light

(1823) St. George

Matinicus Rock Light

(1848) Criehaven

Monhegan Island Light

(1850) Monhegan

Moose Peak Light

(1827) Jonesport

Mount Desert Rock Light

(c.1830)

Nash Island Light

(1838) Addison

Nubble Light

(1879) York Beach

Owls Head Light

(1826) Owls Head

Pemaquid Point Light

(1827) Bristol

Petit Manan Light

(1817) Milbridge

Pond Island Light

(1855) Phippsburg

Portland Head Light

(1791) Cape Elizabeth

Prospect Harbor Point Light

(1850) Gouldsboro

Pumpkin Island Light

(1854) Deer Isle

Ram Island Ledge Light

(1905) Portland

Ram Island Light

(1883) Boothbay

Rockland Breakwater Light

(1888) Rockland

Saddleback Ledge Light

(1839) Vinalhaven

Seguin Light

Seguin Island

(1795) Georgetown

Spring Point Ledge Light

(1897) South Portland

Squirrel Point Light

(1898) Arrowsic

St. Croix Light

(1856) Calais

Two Bush Island Light

(1817) Two Bush Island

West Quoddy Head Light

(1808) Lubec

Whitehead Light

(1807) St. George

Whitlocks Mill Light

(1892) Calais

Wood Island Light

(1808) Biddeford

(Dates indicate original construction; many have been reconstructed.)

The rugged coast and unpredictable waters of Maine have created an environment demanding protection for seafarers. Lighthouses have been built along Maine’s coast since the country began. In fact, there are more lighthouses here than in any other state Maine’s size. There are some 71 lighthouses between Boon Island off York, and West Quoddy Head in Lubec. See also the Lighthouses Photos Galleries.

The lives of the U.S. Coast Guard personnel, who used to attend to about a dozen of the lights, are quite tame compared to those of civilian lighthouse-keepers, who kept long, lonely vigils, saw frequent shipwrecks, and made daring rescues. There are fascinating tales about the keepers, their families, and even their chickens’ endurance of 100-mile-an-hour gales on remote outposts like Matinicus Rock, Mount Desert Light, and Boon Island. Now virtually all of Maine’s lighthouses are automated.

Most lighthouses along the coast used the highly efficient Fresnel lenses. They were of six “orders” or types. Three orders (1, 2, and 3) were designed for coastal lights. A first-order lens, the most powerful, made up of over 1000 prisms, stood up to 10 to 12 feet tall and measured 6 feet in girth and could weigh up to 3 tons. The other were used in harbors or on lakes.

A Brief History

Maine’s light stations played important roles in the growth and development of the state’s maritime transportation network. Located at strategic offshore coastal and river sites, they are the most technologically and architecturally significant elements in an extensive system of navigational aids. Constructed in response to specific local needs, and later as part of a coast-wide pattern, they continue to show the historic growth patterns in coastal communities.

In the early 19th century, the explosion of traffic in Maine’s coastal waters required improved aids to navigation. In addition to the heavy volume of merchant traffic, steam passenger vessels, in service by 1816, connected the coastal and larger river towns with urban areas such as Portland, Boston and New York. Passenger traffic, including pleasure craft, increased dramatically as the growth of summer resorts became a major seasonal industry.

Alexander Parris (1780-1852), a notable civilian contractor, worked on Maine lighthouses. This architect/engineer championed the use of granite, as his Maine commissions demonstrated. His first designs were in 1838 and 1841 for Saddleback Ledge Light and York Ledge Beacon, respectively. Parris’s greatest work came near the end of his long career, beginning with the redesign of Matinicus Rock Light (1846-47). He followed with Mount Desert Rock Light (1847), Libby Island Light (1848) and Monhegan Light (1851). A sixth tower, the 1852 structure at Whitehead Light, can be reasonably attributed to him.

Maine light stations embody, in design and materials, a specialized structural form adapted to survive an often hostile environment. They illustrate an evolutionary process in engineering and technology beginning in the 1790’s.

At minimum a station consists of a light tower. In a few cases these towers contain the entire living quarters and storage facilities. Most, however, are accompanied by an attached or detached keeper’s dwelling. The tower and dwelling are the station’s most prominent components.

A wide range of other structures are important in the light station system. Bell houses and fog signal buildings contain the warning apparatus used during fogs; boathouses shelter what is often the only means of transportation; cisterns collect fresh water for domestic and steam fog signal use; and barns house animals and equipment.

During the early days, oil used to fuel the light (whale oil, lard oil, and various other oils) was often stored inside the lighthouse. By 1890, all except a few lighthouses in the United States were using kerosene. The volatile nature of kerosene necessitated the construction of separate oil houses, which were usually built of fireproof materials such as brick, stone, iron plate, and concrete. Congress issued a series of small appropriations for the construction of separate fireproof oil houses at many light stations. Installation of these structures began in 1888 and was completed about 1918.*

Constructed from a wide variety of materials, Maine’s stations exhibit various shapes and sizes . Towers erected between 1790 and 1851 were built of stone. In many cases local masons used rubble stone found on or near the site. Less frequently, as at Mount Desert (rebuilt 1847), intricately joined granite blocks were employed. These towers share an additional similarity – conical shafts. Most with this design were erected at some of the most hazardous locations on the coast where they required sufficient height and the ability to sustain tremendous destructive forces. Another design of least five stations had a tower mounted atop the dwelling. They were later replaced.

Substantial change in design and materials occurred during the 1850’s. Each new tower was made of brick and a number of the older stations, including West Quoddy Head at Lubec, were rebuilt with brick towers. The more sheltered location of some lights accounts in part for the widespread use of brick. On the other hand, the newly rebuilt (1855) towers at the exposed locations of Boon Island and Petit Manan Island were constructed of granite.

Unlike their predecessors, the 1850’s towers were rarely given a slight conical shape, perhaps because of their reduced height. Most were cylindrical but those at Fort Point and Deer Island Thorofare erected in 1857 had a square shaft. At least three stations were built with towers atop the dwelling, but the design apparently proved faulty and two, Grindle Point and Indian Island, were pulled down and rebuilt during the 1870’s.

Between 1870 and 1880 thirteen Maine stations were either established or substantially rebuilt, continuing the experimentation with new forms and materials. The rebuilt towers at Grindle Point and Indian Island, as well as the newly built Burnt Coat Harbor Light Station (1872), employed a tapered square shaft. In 1875 two light stations (Avery Rock and Egg Rock) were constructed with a square brick light tower around which was the one-and-a-half story dwelling. Another innovation was a steel frame encased by cast iron plates over a brick lining. Employed at the twin towers at Cape Elizabeth (1876), at the rebuilt Little River Station (1876), and at the newly built light at Cape Neddick (1879), these handsome iron structures are among the most architecturally distinct of Maine’s light towers.

During the last phase of light station construction between 1880 and 1910 fifteen complexes were built and two, reconstructed.

Dwellings at Maine’s light stations may be grouped into one of four types. The oldest, no examples of which survive, was a one, or one-and-a-half story rubble stone building with a gable roof. Photographs of Maine’s light stations, probably taken in the 1860s, reveal that the second generation dwellings were very similar in plan. The most intact example of this design is located at Baker Island Light Station (rebuilt 1855).

The influence of architectural fashion on the design of dwellings continued. The construction of Burnt Coat Harbor Light Station (1872) and remodeling of Grindle Point (1874-75) created dwellings very similar in spirit to the gable roofed houses of the 1850’s.

A more typical late nineteenth century keeper’s house is similar to those built at Cape Elizabeth (1876) or Perkins Island (1898). These dwellings include a much larger full two-story block with an asymmetrical L- or T-shaped plan capped by a cross gable roof. Short porches were also introduced at this time.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gambrel roofs punctuated by dormers covered the houses. The gambrel roof is a clear architectural image of the Colonial Revival style influence. The oldest surviving gambrel keeper’s house was erected in 1890 on Bear Island. Among the many others are Marshall Point (rebuilt 1896), Rockland Breakwater (1902) and Isle Au Haut (1907).

Navigation along the coast of Maine’s frequently hampered by dense fogs. Among the many structures that comprised a light station, the fog warning bell houses are now one of the rarest. Many were mounted on simple skeletal frames and struck by hand, but many others had pyramidal frame bell housing structures for the apparatus that automatically operated the bells.

Other devices had been used, but were unreliable. Some stations had a steam powered fog signal, initially a siren and later a whistle. Most existing steam powered fog signals consist of a square or rectangular shaped brick building capped by a low hipped roof that housed the steam generator. The signals that remain in operation are now powered by modern engines, leaving the brick buildings as the most evident historic component of this warning system.

Functionally obsolete buildings and the absence of continuous repair and maintenance provided by a keeper, threaten the existence of virtually every component of a light station in modern times.

Some Accessible Lighthouses

Relive the colorful lore of lighthouses with a visit to one of the many that are accessible by car including these:

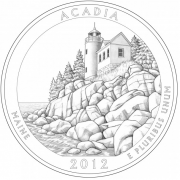

Bass Harbor Head Light (Tremont)

One of the most scenic lighthouses on the Maine coast, situated on the southwest point of Mount Desert Island near the Swans Island ferry terminal. The white conical tower, built in 1858, and the keeper’s dwelling still stand in near-original condition. You can follow the wooden steps to explore the rocks below.

In 2012 this pitcuresque landmark will be found on the back of a U.S. quarter as part of the “America the Beautiful Quarters Program” of the U.S. Mint.

Cape Elizabeth Light (Cape Elizabeth)

Off Rt. 77, with a picnic area, trails, and fishing from the ledges. Formerly a twin tower light, hence the name of its location in Two Lights State Park, the current single beacon, the only one operational since 1924, is four million candle-power, the most powerful of its kind on the New England coast. The first two were built in 1829, the replaced in 1874.

Two Lights State Park, accessible by car, provides sweeping ocean views, fishing off the ledges, and a nearby restaurant.

Fort Point Light (Stockton Springs)

President Andrew Jackson ordered Fort Point Light constructed in 1836. Its thirty-one foot tower provides guidance to traffic passing Fort Point on upper Penobscot Bay. The original picturesque fog bell house still stands. Remains for Fort Pownall, built in 1859, lie nearby along with a picnic area.

Marshall Point Light (St. George)

Four miles south of Tenants Harbor Post Office on Rt. 131; turn left beside the Black Harpoon restaurant. This vintage 1847 light tower marks the south entrance to Port Clyde Harbor and the western entrance to Two Bush Channel. Marshall Point Lighthouse Museum is nearby.

Owls Head Light (Owls Head)

At the tip of a beautiful peninsula off Rt. 73, south of Rockland, you will find Lighthouse Park, overlooking Penobscot Bay. The park has several good picnic spots in the woods and on the shore, great climbing rocks, and tide pools filled with sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and starfish. This lighthouse makes a fine day trip combined with a visit to the nearby Shore Village Museum, which has a fascinating collection of lighthouse artifacts, working foghorns, actual lenses from lighthouse beacons, and narrated tours. Terrific for kids.

Pemaquid Point Light (Pemaquid).

Since the beginning of ship activity in the area, a shoal created hazardous navigation conditions, causing many shipwrecks. As maritime trade increased in the area, so did the need for a lighthouse. In 1826, Congress appropriated funds to build a lighthouse at Pemaquid Point. Although the original building was replaced in 1835, and the original 10 lamps in 1856, the light is still a beacon for ships.

One of Maine’s most visited and photographed lighthouses, and a symbol on the Maine quarter, it is situated on dramatic ledges at the tip of the Pemaquid Peninsula. The old keeper’s dwelling is now the Fishermen’s Museum, with artifacts of Maine coast lighthouses and the fishing industry. The Colonial Pemaquid Restoration and archaeological dig, Fort William Henry, and Pemaquid Beach are nearby.

Portland Head Light (Cape Elizabeth)

Off Shore Road adjoining Fort Williams. This is Maine’s oldest and best known lighthouse, built in 1791 during George Washington’s administration.

Immortalized by the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the beauty of this lighthouse and the encompassing view are inspirational.

Regardless of its imposing protective structure, many a shipwreck occurred within its sight. One was on its very doorstep on Christmas Eve 1886 when the Annie C. Maguire was lost on the rocks virtually at the base of the tower. A hand painted note on those rocks recalls the event.

Spring Point Ledge (South Portland)

The lighthouse, built in the early 20th century, helps mariners avoid Spring Point Ledge and marks Portland Harbor ’s shipping channel. The keeper’s quarters of the light tower are furnished with period furniture, and the third level features interpretative panels describing the light’s construction, how the lens and fog signal operated, and include a number of early photographs and old prints of the light. It is one of the few Maine lighthouses offering public tours and is the only caisson style lighthouse open to the public in the United States.

West Quoddy Head Light (Lubec)

Maine’s famous red and white striped lighthouse. At the easternmost tip of the U.S. in Quoddy Head State Park, this beautiful spot includes fireplaces, picnic tables, and a nature trail along the rim of the high cliffs where whales and dolphins are sometimes sighted. Some areas are restricted for safety reasons.

Many offshore lights are accessible by private boat and by cruises with captains licensed to take passengers on their boats. Some run charters to lighthouses Downeast including Libby Island (at the entrance to Machias Bay), Moose Peak (near Jonesport), Nash Island (near Addison), and Petit Manan (near Milbridge).

Additional resources

Caldwell, Bill. Lighthouses of Maine. Portland, Me. Gannett Books. 1986.

Clifford, Mary Louise and J. Candace Clifford. Women Who Kept the Lights: An Illustrated History of Female Lighthouse Keepers. Williamsburg, VA. Cypress Communications. 1993.

Davis, Deborah. Keeping the Light : A Handbook for Adaptive Re-use of Island Lighthouse Stations. Rockland, Me. Island Institute. 1987.

Duncan, Martina, Director. Portland Harbor Museum. “Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse to Open July 19.” May 29, 2003. (press release)

Feller-Roth, Barbara. Lighthouses: A Guide to Many of Maine’s Coastal and Offshore Guardians. Freeport, Maine: DeLorme Mapping Company, 1988.

Finnegan, Kathleen E. and Timothy E. Harrison. Lighthouses of Maine and New Hampshire. Laconia, New Hampshire: Quantum Printing Corporation, 1991.

*Friends of Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouses. “1903 oil house in need of some TLC.” 1903 oil house in need of some TLC (accessed January 7, 2015)

Maine Historic Preservation Commission. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form: Light Stations of Maine. Augusta, Me. 1987. The “Brief History” on this page is an abridged, edited version of this excellent, detailed account of Maine light stations.

Jones, Dorothy Holder and Ruth Sexton Sargent. Abbie Burgess, Lighthouse Heroine. New York. Funk & Wagnalls. 1969; rev. ed.; rev. ed. Camden, Me. Downeast Press. 1976.

Jones, Ray. The Lighthouse Encyclopedia: The Definitive Reference. Guilford, Conn. Globe Peguot Press. 2004.

Panayotoff, Ted. The Lighthouse at Rockland Breakwater. Rockland, Me. Friends of the Rockland Breakwater Lighthouse. 2002.

Roberts, Bruce. New England Lighthouses: Bay of Fundy to Long Island Sound. Old Saybrook, Ct. Globe Pequot Press. 1996.

Small, Constance Scovill. The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife. Orono, Me. University of Maine Press. 1999.

Snow, Edward Rowe. The Lighthouses of New England. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1973.

Sterling, Robert Thayer. Lighthouses of the Maine Coast and the Men Who Keep Them. Brattleboro, Vermont: Stephen Daye Press, 1935.

Willoughby, Malcolm F. Lighthouses of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: T.O. Metcalf Company, 1929.