Climate Trends

In 2017 the University of Southern Maine, through USM Digital Commons, published “Casco Bay Climate Change Vulnerability Report.” It has been accessible at http://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=cbep-publications (accessed February 20, 2018). The following is a selection of its findings and conclusions.

Temperature

The Casco Bay region has experienced warmer summers; warmer winters; warmer waters; increased drought; increased storminess (evident in higher total precipitation, frequency and intensity); sea level rise; and ocean acidification.

Between 1895 and 2014, the average annual temperature across Maine warmed by about 3°F. Portland, during this same time period, warmed by about 4°F . By mid-century, respected models predict that annual air temperatures across Maine will rise another 3 to 5°F . Modeling done for the Casco Bay watershed in 2009 predicts mid-century temperature increases of 2 to 6°F and end-of-century temperatures in the 3 to 8°F range . Under a high-emissions scenario, summer temperatures could experience a dramatic change up to 10°F warmer.

Warmer Waters

The Gulf of Maine warmed faster between 2004 and 2013 than 99 percent of the world’s ocean. During that period, warming within the Gulf of Maine reached a rate of 0.41°F per year. Since the mid-1990s, water temperatures in Casco Bay have increased about 3°F. In 2012, Casco Bay was subject to an “ocean heat wave”—the largest and most intense such event that the Northwest Atlantic has experienced in three decades—which stretched from North Carolina to Iceland (with especially marked warming in the Gulf of Maine). In response to a 1.8-5.4°F temperature increase, marine species showed marked changes in their seasonal cycles and distribution, abundance, growth and mortality. During the 2012 heat wave, lobsters moved inshore several weeks earlier than normal, causing a spike in landings that outstripped market demand and led to a price collapse.

As regional species shift in response to warmer and more acidic coastal waters, many traditional fisheries, including lobsters, may be disrupted. Some of the most marked shifts in range have occurred in sought-after finfish species like winter flounder, Atlantic cod and silver hake. As climate change progresses, raising the incidence of temperature extremes in coastal waters, failure to anticipate these events and adjust fisheries management accordingly could exacerbate their economic and social impact .

Warmer water temperatures could foster growth of harmful algal blooms in both freshwater lakes and coastal waters. An extensive outbreak of red tide in 2005 caused closures that resulted in $18 million of lost shellfish sales in Massachusetts and Maine.

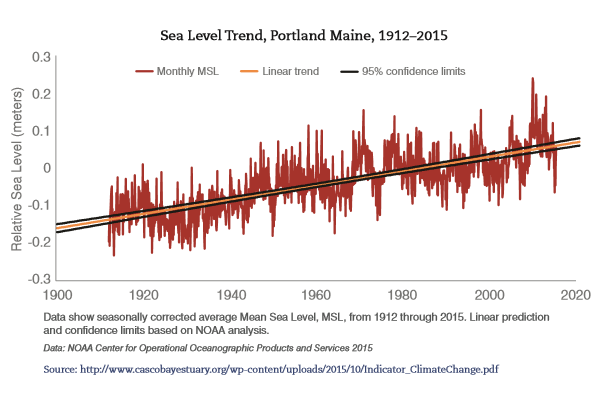

Sea Level Rise

Over the past century, Portland’s tide gauge has shown an average annual increase in sea level of 1.9 mm per year (7.5 inches per century), close to global changes over that period. Sea level at that site during the past two decades has been rising 130 percent faster than this historical rate (ULI 2014).

Based on sea level rise curve scenarios from the US National Climate Assessment, the Maine Geological Survey currently estimates that Casco Bay could potentially experience a 2- to 4-foot rise in sea level by the end of this century. The Maine Geological Survey has statewide potential sea level rise/storm surge inundation maps that depict potential inundation from 1-, 2-, 3.3-, and 6-foot sea level rise scenarios on top of the Highest Annual Tide.

Ocean Acidification

Ocean Acidification

Approximately 26% of human emissions of CO2 is being absorbed by the ocean. When marine waters absorb carbon dioxide, they become more acidic. The ocean is acidifying at a rate at least 100 times faster than at any other time in the past 200,000 years. Waters in

The acidity of Gulf of Maine waters is expected to grow markedly in coming decades, increasing faster than the average for global seas. Increasingly acidic waters can impair marine creatures at all levels of the food web, affecting their ability to grow, resist disease and reproduce. The resilience of the Gulf’s marine ecosystem has already been compromised by the loss of large predatory fish.

More acidic coastal waters make it difficult for juvenile shellfish to build and maintain shells, jeopardizing the future of Maine’s shellfish industry and aquaculture operations. Maine is heavily reliant on shellfish, with 87% of the value of its commercial fish catch based on species such as lobsters, clams, scallops and oysters.