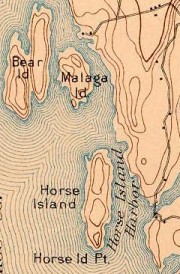

One of the more shameful episodes in Maine history is the treatment of the black residents of Malaga Island, in the New Meadows River just off Phippsburg.

Benjamin Darling, a freed slave, bought the nearby Horse Island in 1794. His son Isaac sold it and probably moved to the unoccupied Malaga Island in 1847. According to author William David Barry, having Black people living in midcoast Maine was not a significant social event at the time.

“. . . any skin color – other than red – was acceptable in those frontier days. In fact, Maine showed little anti-black feeling until the early nineteenth century, and then mostly in Portland.” (p. 55)

Essentially the developing community on the island was left to its own devices throughout most of that century. Then in the 1880’s and 1890’s, the Maine coast blossomed as a tourist destination, with summer homes, resorts, new roads and boat services springing up.

As Maine’s Holman Day noted, in what seems a very modern observation:

Between Kittery Point and Quoddy Head “resorters” have acquired hundreds of headlands and thousands of islands. A phalanx of cottages fronts the sea. Cove and cape, the coast is pretty well monopolized by non-residents; “no-trespass” signs are so thickly set that they form a blazed trail.”

During a time when the concept of “degenerates” and “feeble-minded” people as dangers to themselves and others became popular, the struggling poor residents of Malaga were considered an embarrassment to the new “proper” summer people.

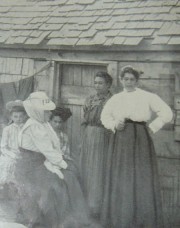

In the early twentieth century, much was made of life on the island in the local press. White civic groups attempted to aid the residents with little effect. Holman Day wrote in the September 1909 Harpers Monthly, after investigating the conditions on Malaga, that “With the exception that their ideas of the social code of morals are primitive, they are blameless so far as their relations with the world go; they are not vicious, they show none of that sullenness that marks similar strata of society, they extend the rude hospitality of their island with touching warmth and sincerity.” p. 530.

Nevertheless, with pressure building to “clean up” the place, the State of Maine bought the island and in 1911 began placing some of the residents in the the Maine Home for the Feeble Minded, the former Pineland Center in Pownal, even though many were normal and active. In 1912 the State made offers for the homes of the remaining residents, offering $50 to $300 each. That year forty-five people were evicted from the island and the State destroyed all the buildings.

In the twenty-first century, the story of Malaga Island has become the focus of attention again. This time by people researching its history and seeking an apology from the State of Maine for its actions a century earlier.

Photo credit: detail from “Entertaining the Missionary – Sunday on Malaga Island,” from Holman Day, “The Queer Folk of the Maine Coast,” p. 527.

Additional resources

Barry, William David, ” The Shameful Story of Malaga Island,” Down East, November 1980, pp. 53-56, 83-85.

Day, Holman. “The Queer Folk of the Maine Coast.” Harper’s Monthly Magazine. September, 1909, pp 521-530.

Dubrule, Deborah, “Evicted: How the State of Maine Destroyed a ‘Different’ Island Community,” Island Journal, Vol. 16.

Greene, Bob. Maine Roots: The Manuel, Mathews, Ruby Family. Brooklyn, N.Y. Family Affair Production. 1995.

Grieco, Jan. “Shudder Island.” The Portland Monthly. October, 2004.

“Malaga Island: A Tragic Expulsion.” Summertime in the Belgrades. July 27 – August 2, 2012. http://www.sumbelnews.com/article.php?id=740 (accessed May 30, 2013)

“Malaga Island, Fragmented Lives.” Maine State Museum. http://www.mainestatemuseum.org/exhibits/malaga_island_fragmented_lives/ (accessed May 30, 2013)

Mitchell, Steve. The Shame of Maine: The Forced Eviction of Malaga Island Residents. Brunswick, Me. S. Mitchell. 1999.

Mosher, John P. No Greater Abomination: Ethnicity, Class and Power Relations on Malaga Island, Maine, 1880-1912. Thesis (M.A.)–University of Southern Maine. 1991.

Gary Schmidt. Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy. New York. Clarion Books. 2004.

Thomas, Miriam Stover. Flotsam and Jetsam. Maine. S.J. Bentley and T.S. Henley. 1998?

UNH Dimond Library. Documents Department & Data Center. Historic USGS Maps of New England & New York. Bath, ME Quadrangle. USGS 15 Minute Series. Southeast Corner. 1894. http://docs.unh.edu/nhtopos/Bath.htm.

Records of the Maine Home for the Feeble Minded, Maine State Archives, Augusta, Maine.