A legislator decides to sponsor a bill, sometimes at the suggestion of a constituent, interest group, public official or the Governor. The legislator may ask other legislators in either chamber to join as co-sponsors.

While the Maine legislator performs a number of different tasks, the legislative function is essentially that of proposing, considering and enacting laws. Each year, Maine’s legislators consider hundreds of ideas for state laws.

The process by which an idea becomes a law is a complicated one, involving many steps. It is designed to prevent hasty or uninformed decisions on matters that can affect the lives of every Maine citizen. Although the process may seem confusing at first, rules and procedures clearly define the steps that apply to every bill.

Legislators, lobbyists, and citizens confer in the halls on the third floor of the State House where the Senate and House of Representatives hold their sessions.

At the legislator’s direction, the Revisor’s Office, Office of Policy and Legal Analysis, and Office of Fiscal and Program Review staff provides research and drafting assistance and prepare the bill in proper technical form.

Ideas for bills come from many different sources: legislators, committees, study groups, lobbyists, public interest groups, municipal officials, the Governor, state agencies and individual citizens.

In some cases, the person or group requesting the legislation may have already drafted the bill. In most cases, however, the legislator turns to a legislative staff office to draft the bill. All legislation, regardless of where initially drafted, is processed and prepared for introduction by nonpartisan legislative staff in accordance with standards established by the Revisor of Statutes.

During the First Regular Session of the Legislature, there are no formal limitations on the bills that may be submitted prior to cloture (dates that bills must be filed). The Second Regular Session of the Legislature is limited by the Constitution to budgetary matters, the Governor’s legislation, legislation of an emergency nature approved by the Legislative Council, legislation submitted pursuant to authorized studies, and legislation submitted by direct initiative petition of the electors.

The Legislature’s Joint Rules establish cloture deadlines for submission of state agency and legislator-sponsored bills during the First Regular Session. The Joint Rules also authorize the Legislative Council to establish deadlines and procedures for introduction of bills to the Second Regular Session or any special session.

Bill Sponsors: Bills have one prime sponsor and may have an unlimited number of cosponsors. A bill’s chances of passage is often improved by having many cosponsors, especially when cosponsors include members of both houses, members of both political parties or member of key committees.

In addition to introducing their own legislation, legislators also act as sponsors for bills proposed by other people or groups. Usually, legislators support bills they sponsor. They may, however, introduce bills “by request” as a service to their constituents when they do not fully support the purpose of the measures. A legislator who wishes a bill to be identified as “by request” should clearly so indicate when filing a bill drafting request.

Bill Drafting and Signing: Before formal introduction, the Revisor of Statutes reviews all proposed bills, and either drafts them or edits any initial drafts to make them conform to proper form, style and usage. When a request for a bill is filed, it is assigned a Legislative Reference (LR) number which is used to track the request until it is printed as a Legislative Document (LD).

The Revisor’s Office serves as the central registry for all bill requests and administers the cloture deadlines established by the Joint Rules. The Joint Rules provide that bill requests that do not contain enough information or direction to draft a bill are not considered complete and may therefore be voided.

The legislator gives the bill to the Clerk of the House or Secretary of the Senate. The bill is numbered, a suggested committee recommendation is made and the bill is printed. The bill is placed on the respective body’s calendar.

After processing by the Revisor’s Office, a bill must be signed by the sponsor and any cosponsors. The Joint Rules require the sponsor and cosponsors to sign the bill or provide changes within deadlines established by the presiding officers. The signed bill draft is then sent up for printing to the Secretary of the Senate or Clerk of the House, depending on whether the presenter (usually the prime sponsor) is a Senator or Representative.

Reference to Committee: The Secretary and Clerk suggest the committee of reference, assign the bill a Senate or House Paper number and LD number, and place it on the next Calendar for consideration in that legislative body. Bills are usually identified and referred to throughout the rest of the session by their LD numbers.

When the Secretary and Clerk disagree on the committee of reference, they refer the matter to the President and the Speaker; if the latter disagree, the Legislative Council resolves the question.

When the Legislature is in recess, the Secretary and Clerk, pursuant to the Joint Rules, refer bills and order them printed. No floor action is required. A notice of the action appears in the House and Senate Calendars.

The suggested reference is made to the committee that seems most appropriate based on the bill’s subject matter. For example, most bills that deal with farming are reviewed by the Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee. However, a bill making tax changes for farmers could be referred to either the Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee or the Taxation Committee.

On occasion, a special committee is temporarily established to consider a bill or bills which cut across committee jurisdictional lines. Occasionally, two committees will jointly work a bill which crosses jurisdictional lines. Usually, this is an agreement worked out between the committees with the committee to whom the bill was actually referred including the other committee in its deliberations.

The bill is referred to one of the Joint Standing or Joint Select committees in the originating branch and then sent to the other body for concurrence.

The vote on reference is the first floor vote taken on a bill. In most cases, approval of the suggested committee reference is a matter of form. Occasionally, the reference is debated and the House and Senate may vote against the suggested reference and refer the bill to a different committee. If the House and Senate cannot agree on which committee will hear the bill, that piece of legislation can go no further in the process.

In a few circumstances, a bill may be engrossed without reference to a committee under suspension of the Joint Rules by a 2/3 vote taken by a division (recorded count). That means that the bill goes directly to the floor of the appropriate body for discussion and action. Engrossing without reference usually occurs when the bill is of an emergency nature and the time to go through the public hearing process is not available.

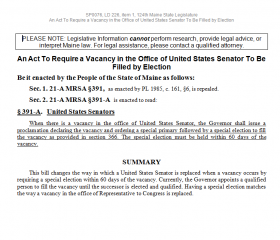

Form of a Bill: There are a number of different types of House and Senate Papers, designed for different purposes. Among these are bills, expressions of legislative sentiment, memorials, orders and resolutions. The discussion here focuses primarily on the particular form of paper called a “bill.” Unlike other papers, a bill, if enacted, becomes a state law. The legislative process is primarily concerned with the drafting, consideration and enactment of bills.

Every bill has certain basic components, in addition to the House or Senate and LD numbers. These include the number of the legislative session, the date of introduction, the name of the committee suggested for reference, the sponsor and any cosponsors, the title, the text and the statement of fact.

In the text, any existing statutory language proposed to be repealed is crossed out and all new language is underlined. When a bill repeals and replaces existing statute, or creates an entirely new statute, all of the text is underlined.

Following the text of the bill is the “Statement of Fact,” a plain English explanation of the content of the bill which is prepared by the Revisor’s Office.

When scheduled by the chairs, the committee conducts a public hearing where it accepts testimony supporting and opposing the proposed legislation from any interested party. Notices of public hearings are printed in newspapers with statewide distribution. Public hearing schedules are posted weekly, during a session, on the State’s web site.

Virtually all bills are reviewed, analyzed and discussed by one or more legislative committees before they are considered on their merits by the full Legislature. Bills are referred to committees by both houses, receive a public hearing, are worked on in committee work sessions, and are given a recommendation, or “report,” by the committee to the whole Legislature.

The Joint Rules authorize 17 Joint Standing Committees, each consisting of no more than 3 members of the Senate and 10 House members. The President of the Senate and Speaker of the House appoint all committee members and committee chairs. Each committee has a House Chair and a Senate Chair.

Each Committee is assigned a legislative analyst from the Office of Policy and Legal Analysis or the Office of Fiscal and Program Review by the respective office directors. The analyst provides nonpartisan staff services to all committee members. Each committee also has a committee clerk who is responsible for maintaining official records of the committee and for providing general clerical and administrative support.

Bill Distribution: Once the committee of reference has been suggested and the bill has been printed, it is distributed to members of the Legislature and to all town and city clerks. Bills are available to the public through the Legislative Document Room (Room 315 – State House). The Clerk of the House provides copies of all bills through a subscription service for which a fee is charged. [Bills are also available free on the Internet as is a mechanism for checking their status.]

Public Hearing: The next step is a public hearing, usually held within the State House or State Office Building. After the House and Senate chairs of each committee set the date and place for public hearings, notices are placed in advance in Maine’s major newspapers and in the weekly Advanced Notice of Public Hearing schedule available at the State House.

The public hearing, presided over by a committee chair, allows legislative sponsors to explain the purpose of the bill and citizens, state officials and lobbyists to tell committee members their views on a bill.

Customarily, the bill’s sponsor testifies first, followed by any cosponsors and other proponents. Opponents testify next, and finally, those persons who would like to comment on the fill but not as an opponent or proponent. At the conclusion of a person’s testimony, committee members may ask questions. The committee’s formal action on a bill comes later at what is called a work session.

Work Session: The purpose of work sessions is to allow committee members to discuss bills thoroughly and vote on the committee’s recommendation, or report, to the Legislature. The committee works with the legislative analyst to draft amendments or review amendments proposed by others. Some bills require several work sessions.

Work sessions are open to the public and, at the invitation of the committee, department representatives, lobbyists and others may address the committee about bills being considered, suggest compromises or amendments, and answer questions. The committee may also ask its legislative analyst to research and explain certain details of the bill.

Amendments are suggested changes to the bill, which may clarify, restrict, expand or correct it. At times, revisions are so extensive that the entire substance of the bill is changed by the amendment. On rare occasions, extensive revision of the bill may take the form of a new draft, rather than an amendment. A new draft is printed as an LD with a new number. Authorization of the President and Speaker is required to prepare a new draft.

Committee Report: The committee’s decisions on bills and amendments are expressed by votes on motions made during a work session; the final action is called a “committee report.” The report a bill receives is often the most important influence on its passage or defeat. Several types of unanimous and divided reports on a bill are possible.

Committee reports shall include one of the following recommendations:

Ought to Pass

Ought to Pass as Amended

Ought to Pass in New Draft

Ought Not to Pass

Refer to Another Committee

Unanimous Ought Not to Pass

With the exception of Unanimous Ought Not to Pass, a plurality of the committee may vote to make one of the other recommendations. When this occurs, a minority report or reports are required.

A unanimous report means all committee members agree. If committee members disagree about a bill, they may issue a divided report, which usually includes majority and minority reports on the bill. Example: a majority ‘ought not to pass’ report and a minority report of ‘ought to pass as amended.’ A less frequent situation occurs when there are more than 2 reports. Example: 6 members vote for ‘Report A,’ ‘ought to pass,’ 5 members vote for ‘Report B,’ ‘ought not to pass,’ and 2 members vote for ‘Report C,’ ‘ought to pass as amended.’

If an ‘ought not to pass’ report is unanimous, the bill is placed in the legislative file and the letter from the committee chairs conveying this report appears on the House and Senate Calendars. When that occurs, no further action may be taken by the Legislature unless a Joint Order recalling the bill from the file is approved by 2/3 of the members of both houses voting in favor of recall. If they do, the bill is considered.

Unless the committee report is a unanimous ‘ought not to pass,’ a legislator may move, at the appropriate time during floor debate, to substitute the bill for the report. A majority vote is required for the motion to proceed.

Prior to reporting out a bill, the committee must determine whether the bill will increase or decrease state revenues or expenditures as well as whether the bill constitutes a State Mandate under the Maine Constitution. The Office of Fiscal and Program Review makes the determination of whether the bill will have a fiscal impact. If it does, the office has the responsibility for producing a fiscal note, which describes the fiscal impact. If the bill constitutes a State Mandate, this fact is also noted in the fiscal note. If the bill does have a fiscal impact, the committee must amend the bill to add the fiscal note. Any necessary appropriation or allocation is also added by committee amendment.

When the bill is reported to the floor it receives it’s first reading and any committee amendments are adopted at this time. The committee reports the bill to the originating body as is, withamendment, with a divided report or with a unanimous recommendation of Ought Not to Pass.

To be enacted, bills must pass through at least four steps on the floor of both the House and Senate: first reading, second reading, engrossment and enactment. An understanding of the Senate, House and Joint Rules is essential to follow and influence a bill’s progress on the floors.

Once a bill is reported out by a committee, it is returned to the house in which it originated. If there is a new draft or committee amendment reported by the committee, it is drafted by the committee’s legislative analyst, prepared by the Revisor’s Office and submitted to the Clerk or Secretary for printing and distribution. The Clerk or Secretary places the title of the bill and the committee report on the Calendar.

The first time the bill, as reported by the committee, is placed on the Calendar, the body votes to accept or reject the committee report, or one of the reports if the committee was divided.

If an ‘ought to pass’ report is accepted in either chamber, the bill receives its first reading by the Clerk or Secretary. Since legislators have copies of the printed bills and committee amendments, a motion is usually made to dispense with a complete reading. After first reading, the bill is assigned for a time for a second reading, which is usually the next day.

If the bill has received a unanimous ‘ought to pass’ or ‘ought to pass as amended’ committee report, the House of Representatives uses the “Consent Calendar,” which allows bills with that report to be listed and to be engrossed for passage after they have appeared there for 2 legislative days, provided there is no objection. However, on the objection of any member, a bill can be removed from the Consent Calendar and debated. Bills which would cause a gain or loss of public revenues cannot be placed on the Consent Calendar. There is not a Consent Calendar in the Senate.

A legislator who wishes to delay a bill at any step of the process to get more information, or for other reasons, may make a motion to “table” the bill until the next day or some other time. A legislator who strongly opposes a bill may make a motion for ‘indefinite postponement.’ If the motion to indefinitely postpone is approved, the bill is defeated. These motions require approval by majority vote in both bodies to succeed.

The next legislative day the bill is given its second reading and floor amendments may be offered. When one chamber has passed the bill to be engrossed, it is sent to the other body for its consideration. The House has a consent calendar for unanimous Ought to Pass or Ought to Pass as amended bills which takes the place of First and Second readings.

A bill may be debated on its merits at several points in the process. The debate may appear uncontrolled to those looking on, but frequently a debating sequence has been arranged. Usually, the chairman of the committee to which the bill was referred speaks first in favor of the committee report, or to answer questions, followed by other committee members who support the bill and by the sponsor. Members indicate to the Speaker or the President that they wish to speak by pressing the electronic switch at their desk or rising in their place. The presiding officers decide whom to recognize and keep track of how many times a legislator has spoken on a particular issue, whether on the main motion, or on a subordinate one.

During floor debate, members communicate with each other by sending messages delivered by pages, or by moving to the back of the chamber to discuss strategy.

Voting: At any point, a legislator or the presiding officer may call for a vote on the current motion on the bill. The vote may be a voice vote, or a vote ‘under the hammer,’ where approval is presumed unless an objection is raised before the presiding officer bangs the gavel. Two other types of votes are a ‘division’ and a ‘roll call.’ For a division, only the total number of votes cast for and against the motion is recorded. For a roll call vote, the members’ names and how they voted are recorded. Any member may request a roll call which requires the support of 1/5 of the members present.

A roll call vote is signaled by the ringing of bells and members are given a few minutes to return to their seats. The Sargent-At-Arms is ordered to secure the chamber and no one is permitted to leave until the vote is recorded. In the House, members vote in a division or roll call by pushing a button at their desks; the results are displayed on two large boards on the front walls. In the Senate, members rise to be counted for a division. When there is a roll call, the Secretary calls the names of the Senators in alphabetical order, and each Senator answers either “Yes” or “No.”

The Maine Legislature records and transcribes all the remarks which are made on the record. A complete account of all the arguments made on bills is available in the Legislative Record, which is generally available within a few days of the debate. Legislative records for the session will be posted on the legislature’s web site as they become available.

Floor Amendments: Floor amendments to a bill may be offered by House and Senate members at appropriate times during floor debate. Requests for floor amendments should be filed with the Revisor’s Office with as much lead time as possible. Floor amendments must be presented to the Clerk or Secretary, numbered, printed, and distributed to members before they may be offered on the floor. If an amendment affects an appropriation in any way or causes an increase or decrease in state revenues, it must also include an amended appropriation or fiscal note.

The bill goes through a similar process. If the second chamber amends the bill, it is returned to the first chamber for a vote on the changes. It may then be sent to a conference committee to work out a compromise agreeable to both chambers. A bill receives final legislative approval when it passes both chambers in identical form.

Passage to be Engrossed: After the debating and amending processes are completed, a vote is taken in both houses to pass the measure to be engrossed. “Engrossing” means printing the bill and all adopted amendments together in an integrated document for enactment. Bills passed to be engrossed are prepared by the Revisor’s Office and sent to the House and then the Senate for final enactment.

Enactment: After being engrossed, all bills must be considered for final passage first in the House and then in the Senate. The necessary vote for enactment is usually a simple majority; there are important exceptions. Emergency bills and bills excepted from the State Mandate provision of the State Constitution require a 2/3 vote of those present. After a bill is enacted by both the House and the Senate, it is sent to the Governor. If it fails enactment in both houses, it goes no further in the process.

If the House and Senate disagree on enactment, additional votes may be taken. These give each house the opportunity to recede and concur (backup and agree) with the other body or to insist or adhere to its original vote.

If the disagreement cannot be resolved, the bill is said to have failed enactment and died between the bodies.

During the debate on a bill, motions for reconsideration and to suspend the rules are often used to aid in reaching a consensus. The House and Senate may develop and pass different versions of the same bill. When this happens, a special “Conference Committee” may be named by the President and Speaker to seek a compromise. A report from a Conference Committee is usually accepted by both the House and Senate; but if it is not, or if the committee is unable to agree, the bill is defeated unless a new Conference Committee is appointed and successfully resolves the disagreement.

Appropriations Table: Bills which affect state revenues or expenditures fall into a special category. Once bills that affect the General Fund or Highway Fund have been passed to be engrossed in the Senate, and enacted in the House, they are assigned in the Senate to the Special Appropriations Table (General Fund) or to the Special Highway Table. They are listed on the Senate Calendar and are held in the Senate for consideration late in the session.

At the end of the session, after the budget bills have been reported out by the Appropriations Committee, and usually after the budget bills have been enacted, the Appropriations Committee and legislative leadership, having received recommendations from policy committees, review bills on the Special Appropriations Table to determine which can be enacted given available General Fund resources. The Transportation Committee follows similar deliberations for bills on the Special Highway Table, considering available Highway Fund resources.

Following those decisions, motions are made in the Senate, usually by the Senate chairs of the Appropriations and Transportation Committees, to remove bills from the special tables and to enact, amend or indefinitely postpone (kill) them. If enacted in the Senate, these bills are sent to the Governor for approval like all other enacted bills. Any of these bills which fail of enactment or require amendment in the Senate are returned to the House for concurrence.

After final passage (enactment) the bill is sent to the Governor. The Governor has ten days in which to sign or veto the bill. If the Governor does not sign the bill and the Legislature is still in session, the bill after ten days becomes law as if the Governor signed it. If the Legislature has adjourned for the year the bill does not become law. This is called a “pocket veto.” If the Legislature comes back into special session, the Governor on the 4th day must deliver a veto message to the chamber of origin or the bill becomes law.

After a bill has been enacted by the Legislature, it is sent to the Governor, who has 10 days (not counting Sundays) to exercise one of three options. The Governor may sign the bill, or allow it to become law without signature.

If the Governor signs it, the bill ordinarily becomes law 90 days after the adjournment of that legislative session – unless it is an emergency measure, in which case it takes effect upon the Governor’s signing or on a date specified in the bill.

If the Governor vetoes the bill, it is returned to the house of origin, where a 2/3 vote of those present and voting in both the House and Senate is required to override. The Governor’s veto message may include comments on particular aspects of the bill and the reasons for rejecting it, possibly raising new issues for legislators to debate. If the Legislature overrides the Governor’s veto, the bill becomes law without gubernatorial approval.

If the Governor does not support a bill but does not wish to veto it, it becomes law without the Governor’s signature, if not signed and not returned to the Legislature within 10 days.

When the Legislature adjourns before the 10-day time limit has expired, a bill on which the Governor has not acted prior to the adjournment of the session becomes law unless the Governor vetoes it within 3 days after the reconvening of that Legislature. If there is not another meeting of that particular Legislature lasting more than 3 days, the bill does not become law.

A bill becomes law 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which it was passed. A bill can become law immediately if the Legislature, by a 2/3 vote of each chamber, declares that an emergency exists. An emergency law takes effect on the date the Governor signs it unless otherwise specified in its text. If a bill is vetoed, it will become law if the Legislature overrides the veto by a 2/3 vote of those members present and voting of both chambers.

Numbering: Once a bill becomes a law, it is assigned a chapter number. This is a consecutive numbering, starting with Chapter 1 for the first law enacted in the First Regular Session, and continuing through all regular and special sessions of that legislative biennium. All laws are identified to the first year of the biennium. Thus laws passed by the 117th Legislature are identified as Chapters of the Public Laws of 1995, even though the laws of the Second Regular Session were passed in 1996. After each session, copies of every individual measure enacted are available from the Engrossing Division of the Revisor’s Office.

Laws of Maine: Following the adjournment of each Regular Session, all public laws, private and special laws, resolves, and constitutional resolutions passed in that year are published by the Office of Revisor of Statutes in the Laws of Maine. These soft bound volumes are available to the public on request and are found in the law libraries in each county.

Codification: The Maine Revised Statutes Annotated, the codified compilation of Maine Public Laws, is updated annually by West Publishing Company in cooperation with the Revisor of Statutes to include changes enacted by each Legislature.

Further Action: After a bill is enacted, it may be affected by subsequent actions, including referenda, regulatory interpretations, and court action.

Referenda: If the Legislature approves by the necessary 2/3 vote of both bodies a resolution proposing a constitutional amendment, that resolution must be submitted to the people for a referendum at the next general election. Constitutional amendments do not require approval by the Governor, but must be approved by a majority of the voters.

A referendum can also result from a successful direct initiative petition by the voters to either enact or repeal a law. After the Secretary of State verifies the signatures on the petitions, the measure is submitted to the Legislature, which may pass that law as submitted, or refer the initiated measure to the people for referendum vote. The Legislature may also enact an alternative version, called a competing measure, in which case both versions are referred to the people for a referendum vote.

A third type of referendum is triggered by a successful petition to exercise the people’s veto. Voters may petition for a referendum to approve or disapprove any law enacted by the Legislature but not yet in effect. If the law is not ratified by a majority of voters in a statewide general election or special election, it does not take effect. This is known as the “people’s veto.”

The Legislature at times inserts referendum provisions in legislation for policy reasons, for instance, substantive amendments to water district charters customarily include a local referendum provision. If the referendum is not approved as provided in the legislation, then those portions of the legislation subject to referendum approval do not take effect.

Finally, the Maine Constitution requires that referenda be held for all bond issues proposed by the legislature.

Agency Rulemaking: Many laws authorize state agencies to adopt rules to implement laws. These rules must be adopted in accordance with the Maine Administrative Procedure Act (the ‘APA’). This Act requires, among other things, public and legislative notice of rulemaking. Once properly adopted, rules have the effect of law.

Court Action: Another way in which laws may be affected is by court action. As a result of cases brought to them, the Maine courts interpret laws passed by the Legislature. Court decisions may clarify the purpose of a law, its application, or the meaning of certain words in the context of the statute. The courts also may determine whether a law conforms to the provisions of the United States Constitution and the Maine Constitution.