| 1836 | Birth in Boston |

| 1854? | Lithography workshop |

| 1857 | Free-lancing, Harper’s Weekly |

| 1859 | National Academy of Design |

| 1862 | Artist for Harper’s |

| 1863+ |

Civil War paintings, Harper’s |

| 1866 | Prisoners from the Front |

| 1867 | Homer returns to New York |

| 1872 | Snap the Whip. |

| 1875 | 1st view of Prouts Neck |

| 1881 | Northumberland, England |

| 1882 | Homer returns to New York |

| 1883 | Summer at Prouts Neck |

| 1884 | Settles at Prouts Neck |

| 1885 | The Fog Warning |

| 1893 | The Fox Hunt |

| 1896 | The Wreck, Carnegie award |

| 1897 | A Light on the Sea |

| 1899 | The Gulf Stream |

| 1906 | Illness, Met buys The Gulf Stream |

| 1908 | Stroke. Begins Right and Left |

| 1910 | Homer dies at Prouts Neck |

National Register of Historic Places – Listings

Homer, Winslow, Studio

(1836-1910) A story is told on one summer day in Maine that a group of well-known vacationing artists from New York found themselves in the vicinity of Prouts Neck in Scarborough–the fabled and secluded haunt of their colleague, Winslow Homer. They sent along a messenger to tell Homer they were in the area and would like to stop by for a visit. When he heard this news, Homer, who could not tolerate being disturbed while he was painting, refused the offer, huffing “Oh, I haven’t any time to waste upon a lot of enthusiastic art students!”

Now the artists took this snub in good stride, but it was typical of the classic image we have of Winslow Homer–a solitary, unfriendly, intent man, wedded to his work, impatient, and disgusted with the world of the city and sophistication. In truth, Homer, one of American’s greatest painters, was quite friendly, courteous and outgoing. True, he favored the country and the rugged coastline over the city, but simply because it was in nature that he found his inspiration.

This inspiration had its roots in his childhood. He was born in Boston on February 24, 1836, the second son of Charles Savage Homer, a hardware merchant and Henrietta Benson Homer, who came from Bucksport and was a painter herself. Six years later his family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, which was then still a country town. Here Homer and his brothers enjoyed the pleasures of the open countryside and it was here that his love of the outdoors was born. His love of art was also fostered in these years and he was known to have been reprimanded more than once in school for dreamily sketching in his notebooks when he ought to have been listening to his teachers.

Fortunately, Homer’s father encouraged his son’s talent and when young Winslow turned 19, Charles Homer apprenticed him to a lithographer in Boston by the name of Bufford. Homer was employed making drawings for the covers of sheet-music, but after two years he had enough and decided to go it alone. He survived on free-lance work, doing many illustrations for Harper’s Weekly, which was a popular and prestigious magazine published in New York. He thought that New York might be a place to get even more work so he moved there in the fall of 1859.

Harper’s offered Homer a staff position, but, with the memory of Bufford’s still fresh in his mind, he declined it, wishing to remain free-lance. He had “a better taste for freedom,” he said. He had also, by this time, decided to become a painter and he took courses at the National Academy of Design as well as a few private lesson from a French artist. This was the extent of his formal training. Despite his desire to move away from illustrating, he ended up doing a great deal of work for Harper’s when the Civil War broke out and the magazine sent him off with the Union Army as an artist-correspondent.

While doing work for the magazine, however, Homer was also busy taking in the world around him with the intention of putting it on canvas. Many of his war paintings depict related moments of life in camp and one painting entitled Prisoners from the Front earned him great recognition at the Academy and established him in the art circles of New York and beyond. The work he did during the war years established him in his field.

Like many artists, Homer made the pilgrimage to Europe where he viewed the works of the great masters. Upon his return, he lived in New York, taking summer trips to New England, the Adirondacks and the Hamptons. Although he often used natural settings, many of his paintings from this period were of middle and upper class people enjoying themselves on picnics or at croquet. There was no hint here of the rough Civil War camps of Homer’s past, nor of the rugged Maine coast that was to come.

In 1881, when he was 45 years old, Homer went to England and spent almost two years at a place called Tynemouth in Northumberland, a dramatic and picturesque locale overlooking the sea. Here he encountered a rugged, determined class of people who eked a precious living from the land and the sea and were very unlike the delicate subjects of his other paintings. He was also exposed to the savage beauty of the wild North Sea and he knew he had found a subject for his work that held special meaning for him. It was in England, many critics say, that Homer’s style changed and it was also here that he took to painting more in watercolor, a medium which was not taken very seriously in his era. It is believed that Homer made watercolor accepted in America as a true art form.

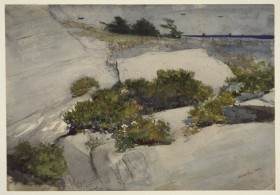

Maine Cliffs (right) has no known copyright restrictions, according to the Brooklyn Museum, which holds the original. The Museum’s brief note reads,

Winslow Homer increasingly subordinated the human figure to the landscape in works produced after he moved to the coastal town of Prout’s Neck, Maine. In this watercolor, he rendered the boulders as an almost abstract series of intersecting planes, highlighted with bright accents of color including the red berries in the shrubs and the blue streak of ocean in the distance. The high horizon line and flattened space betray the artist’s familiarity with Japanese prints.

Homer returned to New York in the fall of 1882. By 1884, he had reached another turning point in his life. He made the decision to leave New York for good and move to a place he had visited on several occasions and liked very much–Prouts Neck in Scarborough.

Homer’s family owned much of the Neck and he took up residence in an old stable which he converted into a studio, with the help of noted architect John Calvin Stevens. It was heated only by a fireplace and a kerosene stove and he had to cut ice in the winter months to get his drinking water, but it was just what he was looking for. The building sat with a full view of the sea and Winslow Homer’s studio right on the edge of the rocky coast and Homer had a protected porch built on the ocean side so that he could work out of doors painting the sea and not be bothered by the weather. It was perfect for him and it was here that he spent the rest of his days.

Homer found in Maine the same inspiration he had discovered during his stay at Tynemouth. The power and beauty of Maine’s rock-bound coast reminded him of the stormy North Sea in England and many say that Homer’s best work was done during this latter part of his career, which he spent primarily at Prouts Neck with occasional trips to the tropics or the Adirondacks and Canada.

Homer was also impressed with Maine’s coastal people–the fishermen, the farmers, the strong, working women–and their, simple rugged lifestyles. He befriended his neighbors and would often call on them in the afternoon or early evening, dressed in best clothes and bearing a bouquet of flowers or perhaps a bottle of something. Many of these people served as models in his paintings or offered him advice. The local stationmaster told Homer once that the birds in his painting, The Fox Hunt, didn’t look like crows as he intended. Homer spent the next few days hanging out at the station with the man, pitching corn in the yard to attract the black birds, and making sketches so he would get it right. Homer’s handyman served as the model for the Coast Guardsman in The Life Line, which was the artist’s first major work produced at Prouts Neck. The old mariner in The Fog Warning, one of Homer’s most famous works, was the owner of a fish house just down the beach.

Thus, far from being a recluse, Homer was a man who enjoyed the companionship of the people he lived and, in a sense, worked with. True, he built special chairs in his studio that were intentionally uncomfortable so that visitors wouldn’t stay too long. True he had a sign that read “Snakes and Mice” which he posted on the path to his house while he was working. True, he was known to chase away visitors from the city who would come to call–but for the lobsterman down the way who wanted to chat or for the fisherman’s wife who just happened to be taking supper out of the oven, Homer always seemed to have time.

Homer died at his studio in Prouts Neck in 1910 at the age of 74. During the quarter century he spent living and working in Maine, he created some of his most memorable and important works. Like his studio, poised at the very edge of the beautiful yet sometimes violent sea, Homer’s central theme was the beauty and danger of peoples’ closeness to nature.

Source: Virtually, with edits, additions, and condensation, verbatim from the Maine Department of Education’s Maine’s Claim to Fame: A Gallery of Personalities. Augusta, Me. The Department. 1990.

Homer, Winslow, Studio, National Historic Landmark, Winslow Homer Road, Prout’s Neck