From “WHITE-TAILS IN THE MAINE WOODS”

by Gerry Lavigne, c. 1998 [major excerpts]

Wildlife Biologist, Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife

Deer Details

Physical Characteristics

Maine is home to one of the largest of the 30 recognized subspecies of white-tailed deer. After attaining maturity at age five, our bucks can reach record live weights of nearly 400 lbs. Most adult bucks, however will normally range from 200 to 300 lbs live weight, and will stand 36 to 40″ at the shoulder. Does are considerably smaller; they normally weigh 120 to 175 lbs live weight. Newborn fawns begin life at 4 to 10 lbs, but grow to approximately 85 lbs live weight in their first 6 months of life.

White-tails have keen hearing, made possible by large ears that can rotate toward suspicious sounds. They have wide-set eyes, enabling them to focus on subtle movements, while maintaining an excellent sense of depth perception. White-tails have a very keen sense of smell enabling them to sense danger, even when visibility is poor. Deer have long graceful legs, enabling them to cover ground quickly by leaping, bounding, turning and outright running at speeds up to 40 mph. Their trademark white tail, when erected, flashes a danger signal to other deer in the vicinity. [The deer pictured above noticed the human presence and immediately lay down, remaining immobile with ears tuned to the observer. A slight movement sent it leaping away.]

[Known once informally as the “Gray Animal Farm,” but officially as the “Game Farm,” it is now The Maine Wild Life Park, located in the town of Gray.]

Deer are carriers of “deer ticks,” which may carry Lyme disease, with painful effects, including joint pain and arthritis, among others.

White-tailed deer communicate using a variety of sounds, ranging from explosive “whooshes” when startled, to the barely audible mews and grunts a doe uses to tend to her fawns. Deer are very expressive; they employ a large repertoire of signals using facial expressions and body language. These postures help to maintain the dominance hierarchy within all deer groups. Deer also communicate using odors, which emanate from a number of scent glands. These glands occur between the toes, on the shins, the hock, the forehead, near each eye, and inside the nose. The contents of each gland, when rubbed onto a tree or the ground, helps deer to know who their neighbors are, and what each deer is doing at any given time.

Bucks annually produce antlers, which are made of bone. Triggered by day length and maintained by hormone production, antlers begin growing in April, and are nurtured by a velvety outer network of skin tissue and blood vessels. Velvet is shed when growth is complete in late August and September. The hardened, polished antlers remain until they are shed in late December to early March. In white-tails, antlers allow bucks to advertise and demonstrate their dominance; hence they play a role in reproduction. A buck’s first true set of antlers normally is grown by age 1 ½. Buck fawns, however, begin growing the antler base at 1 month of age. This base develops into 2 or 3 inch velvet-covered “nubbins” by early winter. White-tailed does sometimes produce antlers, but this is rare. Does that do sprout antlers typically are older (5 to 15 years old); their antlers are usually velvet-covered spikes. Most antlered does remain fertile.

Each year, deer produce two coats of hair, each adapted to seasonal climate. In late spring, deer grow a coat of fine, short reddish hair. This pelage allows ample air circulation and helps the deer to stay cool in summer’s heat. During September, deer molt to a highly insulative coat which consists of a dense layer of fine woolly hair under a layer of long hollow brown, gray, and white guard hairs. The guard hairs can be erected to form a very thick insulative coat, which protects against the cold winds of winter. Fawns are born with a reddish-brown coat dappled with white spots. This affords excellent camouflage against detection by predators in the summer. By early autumn, fawns grow the typical winter coat.

Another adaptation for survival is the deer’s habit of storing fat for the winter. In autumn, deer accumulate fat under the skin, in the viscera, between the muscles, and in the hollow bones of the legs. This fat layer can comprise 10 to 25% of a deer’s body weight by late fall. In winter, fat is reabsorbed to provide much-needed energy to supplement inadequate diets of woody browse.

Natural History

Habitat. Major habitats that provide food and cover for white-tailed deer in Maine are forest lands, wetlands, reverting farmlands, and active farmlands. Forest stands containing little or no canopy closure, wetlands, and reverting and active farmland yield the largest and best forage within reach of deer. However, stands of mature conifers with tree height greater than 30 ft. and crown closure of greater than 60% provide critical winter habitat for deer.

Habitat. Major habitats that provide food and cover for white-tailed deer in Maine are forest lands, wetlands, reverting farmlands, and active farmlands. Forest stands containing little or no canopy closure, wetlands, and reverting and active farmland yield the largest and best forage within reach of deer. However, stands of mature conifers with tree height greater than 30 ft. and crown closure of greater than 60% provide critical winter habitat for deer.

Currently, 94% of Maine is considered deer habitat; this excludes developed parts of the state. In practice, even a portion of Maine’s developed land is currently occupied by deer. Wintering habitat is more limited in availability, comprising only 2 to 25% of the land base in various parts of the state. Protection of critical wintering habitat is a major focus of deer management activities by the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Food habits. Deer are highly selective herbivores, concentrating on whatever plants or plant parts are currently most nutritious. Finicky eaters, deer opt for variety over quantity, when feeding along in the woods and fields. Deer consume grasses, sedges, ferns, lichens, mushrooms, weeds, aquatics, leaves (green and fallen), fruits, hard mast (acorns, beech nuts, etc.), grains, and twigs and buds of woody plants. Contrary to popular belief, deer consume twigs and buds of dormant trees and shrubs only when more nutritious foods are unavailable. When restricted to woody browse, deer inevitably lose weight.

During the course of the year, deer may browse several hundred species of plants. A few are highly preferred; many others are consumed only when the best have been depleted. Overabundant deer populations can reduce the abundance of preferred forages, while causing unpalatable plants to become more common. Extremely abundant deer can literally eat themselves out of house and home. At these times, hungry deer are underweight, prone to starvation and disease, produce fewer fawns, grow smaller antlers, and create increased conflicts with homeowners, gardeners, farmers, forest landowners, and motorists.

Reproduction. The peak breeding season for deer in Maine occurs during mid-November, although some breeding may occur in October and as late as January. The onset of the rut in bucks and estrus in does is controlled primarily by decreasing day length. Does in estrus are receptive to breeding for roughly 24 hours, and if not successfully bred, they will come into heat every 28 days, until early winter. Bucks establish and maintain a dominance hierarchy; typically the majority of does in an area are bred by the most dominant bucks.

Gestation period for deer is roughly 200 days, after which well-nourished adult does give birth to twins, triplets, and rarely, quadruplets. Fawn and yearling does typically produce one fawn, if they conceive at all. The peak fawning season in Maine is mid-June. In a typical year, each 100 Maine does will give birth to about 130 fawns. However, early fawn losses tend to be high; only 60 to 80 of these young deer typically survive their first 5 months of life.

Longevity. White-tailed deer can live to 18 years, but few deer in the wild live that long. Does typically live longer than bucks, presumably because rutting behavior predisposes bucks to higher losses due to hunting, motor vehicle collisions, physical injuries, and depletion of fat reserves going into the winter. Deer populations subjected to high hunting mortality are comprised of predominantly young deer. Conversely, a greater proportion of deer annually survives to older age classes within lightly hunted herds. See the hunting garb worn in the 1950s in this amateur film from Northeast Historic Film.

Longevity. White-tailed deer can live to 18 years, but few deer in the wild live that long. Does typically live longer than bucks, presumably because rutting behavior predisposes bucks to higher losses due to hunting, motor vehicle collisions, physical injuries, and depletion of fat reserves going into the winter. Deer populations subjected to high hunting mortality are comprised of predominantly young deer. Conversely, a greater proportion of deer annually survives to older age classes within lightly hunted herds. See the hunting garb worn in the 1950s in this amateur film from Northeast Historic Film.

Movements. Summer home ranges (area that an animal lives within) for deer in Maine are generally 500-600 acres, but can vary from 150 to more than 2,000 acres. Movement by deer from summer to winter range can vary from less than a mile to more than 25 miles, depending on availability and suitability of the winter range. Deer are not generally territorial (defend their home range against intrusion of other deer). However, pregnant does will defend a small birthing area (less than 20 acres) against intrusion by all other deer, for about a month.

Historical Management in Maine

Population and distribution trends. During the past 400 years, ever-changing patterns of man’s use of the land, predation, climate cycles, and disturbances such as fire, wind and flood have created conditions which either favored or precluded healthy populations of deer in Maine. When Europeans first colonized Maine, white-tails occurred only in the mid and south coastal part of the state; moose and caribou occupied the vast interior forests of the time.

During the next two centuries, the climate moderated, forests were logged and/or cleared, and major predators such as the wolf were extirpated. By the late 1800’s, deer had colonized all Maine towns. During this time, deer abundance often followed cycles of extreme abundance to scarcity, depending on the amount of re-growth after logging, or after wildfire or insect defoliation opened the forest floor to sunlight. These events never occurred at the same time throughout the state. Hence deer abundance was always (and remains) patchy, depending on local conditions

More Videos!

Additional resources

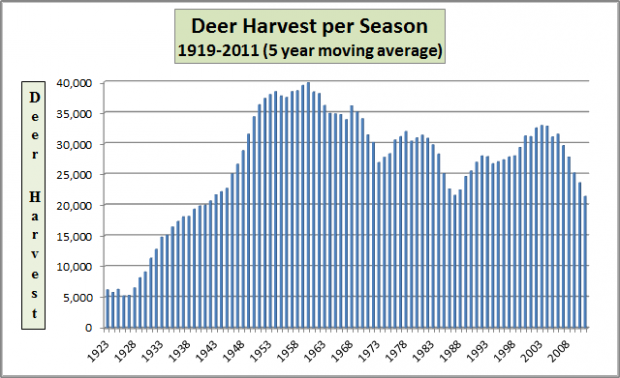

Chart data: Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife

Banasiak, Chester F. Deer in Maine. Augusta, Me. Dept. of Inland Fisheries and Game. 1961.

Gill, John. Effects of Pulpwood Cutting Practices on Deer. New York, N.Y. 1957. (Cataloger Note: Reprinted from Proceedings, Society of American Forester, 1957) [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Holmes, Lawrie. Ways of Deer and Laws of Men. Bar Harbor, Me. Bar Harbor Times Publishing Co. 1949.

Lavigne, Gerald R. White-Tailed Deer Assessment and Strategic Plan 1997. Maine. Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Augusta, Me. 1999. http://www.maine.gov/ifw/wildlife/species/plans/mammals/whitetaileddeer/speciesassessment.pdf (accessed August 23, 2012)

Maine. Land Use Regulation Commission. “Policies Concerning Deer Yard Issues.” Augusta, Me. 1982. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Maine. Land Use Regulation Commission. “Land Use Regulation Commission’s Policy Statement on Deer Wintering Areas.” Augusta, Me. The Commisison. 1991.

Wildlife Division Research & Management Report. Various Years.

Augusta. Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. http://www.maine.gov/ifw/wildlife/species/deer/index.htm (accessed November 6, 2011)