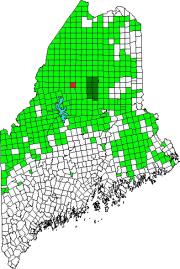

[chu-SUN-cook] is an unorganized township (T5 R13 WELS) in Piscataquis County.

The name means “at the place of the principal outlet,” according to McCauley. Chesuncook Lake extends south to T3 R12 WELS.

Ripogenus Dam, constructed 1916-1920 “at the place of the principal outlet,” vastly expanded the lake and provided water storage for log drives down the Kennebec River. With the completion of the McKay hydroelectric station in 1953, the dam supplied power to paper mills downstream.

In 2005 Bangor Daily News reporter Diana Bowley captured Chesuncook Village location succinctly:

50 miles north of Greenville, the Village is [was] accessible only by boat, floatplane, or a 4-mile overland hike. On the shore of Chesuncook Lake, the state’s third-largest, the isolated community overlooks Mount Katahdin. Ten people live in the village year-round. In summer it can swell to 100.

The renamed Chesuncook Lake House described itself as “A small Wilderness Lodge, built as a farmhouse/ boarding house in 1864 at Chesuncook Village, to supply logging operations in Northern Maine’s Wilderness.” The house burned to the ground on March 17, 2018. The owners said they would rebuild.

Gero Island Public Reserved Land in Chesuncook Township is a large island in Chesuncook Lake. The water access campsites on the shore are popular with anglers and canoeists paddling the West Branch of the Penobscot River.

National Register of Historic Places – Listings

Chesuncook Village District

[northwest shore, Chesuncook Lake] The 3,845 acre parcel also includes most of historic Chesuncook Village on the mainland. The Village is at the head of the lake near the mouth of the West Branch of the Penobscot River. Some observations from Thoreau’s “Chesuncook” article in the Atlantic in 1858:

On entering the lake, where the stream runs southeasterly, and for some time before, we had a view of the mountains about Ktaadn (Katahdinauquoh one says they are called), like a cluster of blue fungi of rank growth, apparently twenty-five or thirty miles distant, in a southeast direction, their summits concealed by clouds.

Ansell Smith’s, the oldest and principal clearing about this lake, appeared to be quite a harbor for batteaux and canoes; seven or eight of the former were lying about, and there was a small scow for hay, and a capstan on a platform, now high and dry, ready to be floated and anchored to tow rafts with. It was a very primitive kind of harbor, where boats were drawn up amid the stumps,—such a one, methought, as the Argo might have been launched in.

As we approached the log-house, a dozen rods from the lake, and considerably elevated above it, the projecting ends of the logs lapping over each other irregularly several feet at the corners gave it a very rich and picturesque look, far removed from the meanness of weather-boards. It was a very spacious, low building, about eighty feet long, with many large apartments. The walls were well clayed between the logs, which were large and round, except on the upper and under sides, and as visible inside as out, successive bulging cheeks gradually lessening upwards and tuned to each other with the axe, like Pandean pipes.

There was also a blacksmith’s shop, where plainly a good deal of work was done. The oxen and horses used in lumbering operations were shod, and all the iron-work of sleds, etc., was repaired or made here. I saw them load a batteau at the Moosehead carry, the next Tuesday, with about thirteen hundredweight of bar iron for this shop.

Ansell Smith had several other buildings including an ice house and a handsome barn. He owned two miles of shore by half a mile back, though only about 100 acres were cleared in 1853. He cut about seventy tons of hay on the land.

His Chesuncook camp was rapidly becoming the focal point for the loggers. In 1859 the Chesuncook settlement was acquired by John H. Eveleth of Greenville. In 1864 he built the large Chesuncook House. Soon several other men and their families squatted on nearby state land and supported themselves by raising hay, oats, and potatoes for the lumbermen.

The 1972 photo was captioned “Great Northern Paper Company.” “Camps at ‘Graveyard Point'” In 2017 the only surviving building is the one identified by the red arrow. The Point and some land abutting the Village are now part of Maine’s Public Reserved Lands.

There were sixty-five residents in 1900; twenty years later there were two hundred and forty-seven as the Ripogenus Dam was under construction. In 1921, what was once a “collection of rickety sheds” was made a plantation; twelve years later, when the population had dropped to below seventy, it was deorganized. By 1950 there were only sixteen people left.

The old schoolhouse is now a seasonal community church and social gathering place. Here it is in 2017:

The village cemetery(below) was moved from Graveyard Point in 1916 before the Ripogenus Dam was completed and would raise the water level, threatening the old cemetery. Now the cemetery is off the Village Road near the Village. [N46° 3′ 32.60″ W69° 24′ 45.47″] The earliest person in the cemetery died in 1855. Most recent was a World War II Navy veteran who died in 1992.

Chesuncook Lake

Chesuncook is Maine’s third largest lake. It played a key role in the logging/lumbering period of the 19th century. Chesuncook Lake was formed by the construction of Ripogenus Dam in 1916. This 92 foot dam impounds Ripogenus Lake, Chesuncook Lake, Caribou Lake, and Moose Pond.

Additional resources

Black & white photos from Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. “National Register of Historic Places: Property Photograph Form: Chesuncook Village.” Augusta, Me. 1973. Photo credit: Kenneth Morrison. Photo dates: August 9, 1972. Image source: National Register of Historic Places: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/text/73000262.PDF (accessed December 14, 2014)

1954 USGS 15 Minute Series, Chesuncook, ME Quadrangle, Northwest Corner, is from the University of New Hampshire Dimond Library online, accessed 7/24/2004, at http://docs.unh.edu/nhtopos/Chesuncook.htm. Click map for larger version.

Bowley, Diana. “Chesuncook Village in turmoil; Property dispute strains neighborliness at isolated outpost.” Bangor Daily News. September 15, 2005. P. A1.

Gagnon, Lana. Chesuncook Memories. Greenville, Me. Chesuncook Village Church Committee. c1989.

“Historic 150-year-old Maine inn destroyed by fire.” Bangor Daily News. March 17, 2018. https://bangordailynews.com/2018/03/17/news/piscataquis/historic-150-year-old-maine-inn-destroyed-by-fire/ (accessed March 21, 2018)

Lane, Michael Laurence. A Company Town: The History of Chesuncook Village, Maine, 1830-1971. c1996. Thesis (Honors)–University of Maine, 1996. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Mundy, James. “NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY – NOMINATION FORM: Chesuncook Village.” Augusta, Me. Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. April 11, 1973. http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/text/73000262.PDF (accessed December 7, 2014)

“Lodging at the Chesuncook Lake House & Cabins.” http://www.greatnorthernvacations.com/Lodging-.html (accessed December 7, 2014)

McCauley, Brian. The Names of Maine: How Maine Places Got Their Names and What They Mean.

Thoreau, Henry David. “Chesuncook.” Atlantic Magazine. June 1858. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1858/06/chesuncook/6386/ (accessed October 20, 2011)

Thoreau, Henry David. Katahdin and Chesuncook, by Henry D. Thoreau. From “The Maine Woods”; abridged and ed. by Clifton Johnson. Boston, New York [etc.] Houghton Mifflin Company. c1909.

Addresses restricted: Archeological Sites No. 133.7, 133.8, 143–23, 143–52, 143–53, 143–57, 143–79; Willard Brook Quarry