As Maine communities began to lose some of their frontier aspects in the early 19th century and assumed a more settled appearance, rudimentary civic improvements were initiated. Among these improvements in the largely agricultural world of rural Maine was the regulation of the livestock which were becoming numerous. To control this problem towns constructed shelters, cattlepounds, for the temporary control of wayward animals. In 2004, 21 of these structures in Maine had been verified, and their condition varies from almost unrecognizable to good.

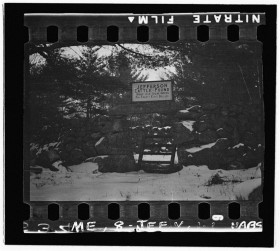

See examples at Brooklin, Charlotte, Greenwood, Harpswell Center, Jefferson, Orrington, Otisfield, Pownal, Sedgwick, Turner, and Waldoboro.

Farmers have always found it necessary to control wandering livestock. In the earliest, 17th century settlements of southern New England, cattle, sheep and swine were grazed on commonly held town lands (“town commons”) located outside the denser residential areas. Inevitably some livestock found their way into cultivated fields and gardens. This had the potential to threaten both the animal and human food supplies in these communities, many of which existed at the subsistence level during the early decades of settlement.

By 1635, the courts of Massachusetts Bay ordered that every town under its jurisdiction construct a strong impoundment in which the wayfaring beasts could be held until claimed by their owner and returned to the pasture. This action was the origin of a class of common, publicly-supported and ordained structures found in almost every agricultural community in New England: the Town Cattle Pound. With the exception of extreme southern and coastal locations, the majority of Maine’s development started much later, in the decades after 1750. Although heavily settled by immigrants from the southern New England States, the patterns of land distribution in Maine had shifted. Few towns designated common pastures, rather individual settlers were expected to care for their own livestock.

1807 Circular Stone Cattle Pound in Orrington

Noting that “gardens were small and the return from fencing them was large,” one historian asserts that the greater acreage required for pastures made them “difficult and expensive” to fence, and that “with near neighbors, cattle could easily stray from one pasture to another.” (Locke, p.214). Thus, the institution of the cattle pound continued to be called upon in Maine, albeit in response to slightly different circumstance. William Locke’s history of cattle pounds in Maine is useful in understanding the important role these public structures played in maintaining order in agricultural communities. The following excerpt is from “The Rise and Demise of the Cattle Pound Harpswell and Maine”, published in 1993/4.

“At the earliest town meetings there were angry demands for an end to damage by marauding cattle. Towns may have hastened their incorporation partly because the election of pound keepers was apparently accepted as establishing a legal basis for impounding strays.From the beginning several implicit concepts underlie the pound solution to the stray cattle problem: first, the owner was responsible for damage done by his animals; second, it was in the public interest that the person harmed or others should round up and drive offending animals to the pound – originally the pound keeper’s barn or farmyard; third, to get his animals back, the owner should pay for damage done. Later, two more concepts were added: the owner was to pay for the cost of feeding and caring for impounded animals, and fines were to be levied on the owner by the town. Eventually, the state legislature incorporated these and other sanctions.”

“When pound keeping in barns and in farmyards became too onerous, towns throughout the District or later the State of Maine authorized construction of one or more log pounds in strategic locations on land loaned for the purpose. No money was appropriated. Trees were there for the felling, and neighbors, no doubt, joined in the common effort, as they did for roads and barns. Later on, more prosperous voters would appropriate money to pay for the work. Then log pounds were replaced by more secure and permanent stone structures.” (Pages 214-215).

Indeed, within the first year of statehood, the Maine Legislature passed two resolves requiring that towns construct pounds for “curbing stray beasts,” although by this time many town had already fulfilled that decree, either with a wooden or a stone pound.

Text virtually verbatim from National Register of Historic Places, Registration Form: Jefferson Cattle Pound.

Additional resources

Allport, Susan. Sermons in Stone. (New York: W.W. Norton and Co.), 1990.

Locke, William. “The Rise and Demise of the Cattle Pound Harpswell and Maine” in Maine Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 3-4, Winter-Spring 1993-1994. (Portland, Maine), p. 210-221.

Shaw, Dick. “Town Pounds In Maine Have All But Disappeared.” Lewiston Evening Journal Magazine Section. Lewiston, Maine. (September 28, 1974), p. 4A.

“The Jefferson Cattle Pound” in The Lincoln County News. Damariscotta, Maine. (July 3, 1980), p. 14.