| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 7,873 |

| 1980 | 7,838 |

| 1990 | 8,854 |

| 2000 | 9,068 |

| 2010 | 9,015 |

| Geographic Data | |

|---|---|

| N. Latitude | 43:33:37 |

| W. Longitude | 70:12:38 |

| Maine House | Dist 30,32 |

| Maine Senate | District 29 |

| Congress | District 1 |

| Area sq. mi. | (total) 58.4 |

| Area sq. mi. | (land) 14.7 |

| Population/sq.mi. | (land) 613.3 |

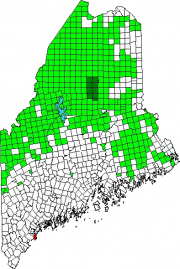

County: Cumberland

Total=land+water; Land=land only |

|

Clipper Ships Built Here

- Black Squall–1850

- Snow Squall–1851

- Warner–1851

- Phoenix–1853

- Portland–1853

[CAPE ELIZ-ah-beth] home to the iconic Portland Head Light lighthouse, is a town in Cumberland County, incorporated on November 1, 1765 as a District from a portion of ancient Falmouth, most of which became Portland in 1786. On August 23, 1775 it was incorporated as a town.

[CAPE ELIZ-ah-beth] home to the iconic Portland Head Light lighthouse, is a town in Cumberland County, incorporated on November 1, 1765 as a District from a portion of ancient Falmouth, most of which became Portland in 1786. On August 23, 1775 it was incorporated as a town.

On March 15, 1895 the town was split, a portion forming South Portland and the remainder retaining the name Cape Elizabeth. The sharp drop in population in the chart below documents the results of the division.

The earliest European presence was on Richmond Island, off the southern portion of the town. It was visited about 1605 by Samuel de Champlain and was the site of a trading post in 1628.

Sprague Hall, Grange No. 242 (2002)

The area was first settled by Europeans in the 1630’s and shared the difficulties of frontier life and Indian raids as did the surrounding “ancient Falmouth” area. In 1635 John Winter, who had a fishing station there, established Maine’s first shipyard on Richmond Island. Letters to his patron in England describe the scene, according to William Rowe:

We see the various buildings go up, the boats’ crews arrive from England go out with their lines and bait, returning with their fare, sometimes good, sometimes light. . . . We read Winter’s orders to his patron for clothing, strong waters, and fishing gear, or the iron work of a vessel he is building.

The clipper ship Snow Squall was built at the Alford Butler shipyard in 1851, along with others in Cape Elizabeth.

Currently a wealthy suburb of Portland, the town has a scenic coastline and a series of attractions including lighthouses at Two Lights State Park, Crescent Beach State Park, Fort Williams, and Portland Head Light. Just offshore shines Ram Island Ledge Light Station.

Olympic gold medalist runner Joan Benoit Samuelson was born in Cape Elizabeth, as was film director John Ford.

Two Lights State Park is off Route 77 where twin lighthouses sit at the end of Two Lights Road. In 1828 they were the first twin lighthouses on the Maine coast. The eastern light is an active, automated station, visible 17 miles at sea. The western light, now a private home, ceased operating in 1924. Picnic tables facing the ocean afford visitors spectacular views. Shoreline trails offer views of ships sailing into and out of Portland Harbor. (See more below.)

Form of Government: Council-Manager

Additional resources

See also South Portland

Cape Elizabeth (Me.). Collected manuscripts. 1730-1865. References are made to the following: Oakes Angier, John Avery, Henry Baldwin, Barrett Potter, Benjamin Blackman, Jonathan and Joseph Cobb, William Davis, Benjamin Dix, David Drowne, John Emery, Moses Gill, Rebecka Goodwill, Samuel Haines, Capt. Hammen, William Hammond, Edward Hines, Samuel Jackson, Eleanor Lee, North Proctor, Joseph Sawyer, Benjamin Thrasher, Samuel Treat, Nancy Thurston, Stephen Thurston, John Wadsworth, Joshua Webb, Lucy Wheeler. Access restricted to serious research. Includes receipts, official lists, military orders, memoranda, commissions, accounts, one each: indenture, license, deed and affidavit. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

Cape Elizabeth: Past to Present. Portland, Me. Associated Graphics/Portland Lithograph. 1991.

Collections from Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Cape Elizabeth. Town of Cape Elizabeth. 1965.

Isaacson, Dorris. Maine:A Guide Downeast, p. 462.

Jordan, William B. A History of Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Bowie, MD. Heritage Books. 1987, 1965.

Jordan, William B. Chapters in the Early History of the Town of Cape Elizabeth, Maine. 1953.

Ledman, Paul J. A Maine Town Responds: Cape Elizabeth & South Portland in the Civil War. Cape Elizabeth, Me. Next Steps Publishing. 2003.

*Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. Augusta, Me. Text and photos from National Register of Historic Places.

**United States. Department of the Interior. National Park Service. “Ram Island Ledge Light Station.” https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/68594c58-2669-4187-825b-e43388f0b654?branding=NRHP (accessed February 20, 2017)

Ray, Roger B. Cape Elizabeth and the American Revolution. Cape Elizabeth, Me. 1975.

Rowe, William Hutchinson. The Maritime History of Maine: Three Centuries of Ship Building and Seafaring. W.W. Norton. 1948. Reprinted: Gardiner, Me. Harpswell Press. 1989. Quote from p. 25.

Smith, Jared A. Sketch of Portland Harbor, Maine showing the improvements made in 1866-86, also projected improvements. [cartographic material] Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office. 1886. (including portions of Cape Elizabeth)

South Portland and Cape Elizabeth. Dover, N.H. Arcadia Publishing. 1995. (pictorial)

Thompson, Kenneth E. Portland Head Light & Fort Williams: an illustrated history with a walking guide map. Portland, Me. Thompson Group. 1998.

National Register of Historic Places – Listings

Photos, and edited text are from nominations to the National Register of Historic Places researched by Maine. Historic Preservation Commission.

Full text and photos are at https://npgallery.nps.gov/nrhp

Beckett’s Castle

[off Maine Route 77 in Delano Park] Beckett’s Castle is an early example of a recreational building when seashore property became appreciated as suitable for amusement and relaxation. Sylvester Blackmore Beckett was born in Portland, May 16, 1812, the son of English parents. Although never attending college, he acquired a fine classical education, became a prominent journalist and articulate writer. He was admitted to the bar in 1859 and spent much of his time administering and settling estates. Beyond this he was an artist, poet, and amateur ornithologist of some distinction. Reportedly he was an eminently social, kindhearted, companionable man.

Beckett planned and built, largely with his own hands, this stone cottage on the shore of Cape Elizabeth. It quickly became known as Beckett’s Castle and became a favorite haunt of Portland’s literary circle. Invitations to social gatherings held there were highly prized. Guests were served expansive dinners cooked in primitive fashion in a large fireplace. At his death on Dec. 2, 1882, the cottage passed into the hands of his only surviving child, Mrs. George W. Verrill, whose son sold it to Col. Walter Singles. In 1974 is was owned by the Colonel’s grandson. *

In 2017 this “haunted” structure was for sale at $3.35 million.

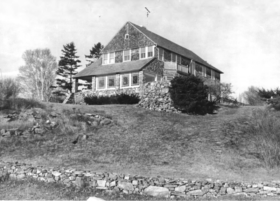

Brown, C. A., Cottage

[9 Delano Park] The 1887 C. A. Brown House is significant mainly because it is a well developed work in the Shingle Style, that grew in importance in the late 19th century, chiefly in coastal summer homes. Its concern with matching the design of the building to its site was a foreshadowing of a trend in architecture which was to reach a fuller development with such masters as Frank Lloyd Wright. It is also important in that it was designed by a Maine architect, John Calvin Stevens (1855-1940), who achieved national prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not only for his designs but for his theories of architecture concerning how a building reflects both its spatial and temporal locations. Stevens was an early advocate of what may be called organic architecture, matching the building to its surroundings. Because of this environmental and esthetic concern, his sea-side cottages are much better adapted to their locations than are his city buildings. The effect was achieved by the use of local materials in a color scheme harmonious with the natural features of the landscape. Thus, the stones in the foundation and lower part of the Brown House are “weathered fieldstone, the very color of the ledges out of which the building grows,” according to Stevens. These stones “had lain for a century and a half in a farm wall, where, it is said, they were originally piled up by slaves. Covered with gray moss and lichens, their color effect was beautiful; and, in order to preserve their unique beauty, they have been laid with their old faces exposed.”

[9 Delano Park] The 1887 C. A. Brown House is significant mainly because it is a well developed work in the Shingle Style, that grew in importance in the late 19th century, chiefly in coastal summer homes. Its concern with matching the design of the building to its site was a foreshadowing of a trend in architecture which was to reach a fuller development with such masters as Frank Lloyd Wright. It is also important in that it was designed by a Maine architect, John Calvin Stevens (1855-1940), who achieved national prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not only for his designs but for his theories of architecture concerning how a building reflects both its spatial and temporal locations. Stevens was an early advocate of what may be called organic architecture, matching the building to its surroundings. Because of this environmental and esthetic concern, his sea-side cottages are much better adapted to their locations than are his city buildings. The effect was achieved by the use of local materials in a color scheme harmonious with the natural features of the landscape. Thus, the stones in the foundation and lower part of the Brown House are “weathered fieldstone, the very color of the ledges out of which the building grows,” according to Stevens. These stones “had lain for a century and a half in a farm wall, where, it is said, they were originally piled up by slaves. Covered with gray moss and lichens, their color effect was beautiful; and, in order to preserve their unique beauty, they have been laid with their old faces exposed.”

The summer cottages were more readily adaptable to these theories because of their informality and minimum of functional requirements. Thus, a summer house could be made to flow from, and participate in, its environment in a way that a city building could not. Large piazzas and picture windows were thus used which would not have been feasible in an urban structure.

The summer cottages were more readily adaptable to these theories because of their informality and minimum of functional requirements. Thus, a summer house could be made to flow from, and participate in, its environment in a way that a city building could not. Large piazzas and picture windows were thus used which would not have been feasible in an urban structure.

The C. A. Brown House is noteworthy as one of the finest examples of the mature Shingle Style cottage architecture, built by an architect prominent in Maine and nationwide.* [Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. photos]

Crescent Lodge

Crescent Lodge in is a former one-room schoolhouse that has functioned as a social clubhouse since 1931. The simple Greek Revival style building is significant for its association with the Ladies’ Union and other Cape Elizabeth organizations and clubs.

The Ladies’ Union was created in the late 1800s to provide aid to local individuals, institutions and associations. After acquiring the former school in 1931, the Ladies’ Union held their meetings in the lodge and rented or loaned the space to other social clubs or individuals.

Located in the southern portion of town within a half mile of the ocean, the property was used by as a clubhouse from 1931 to 1968. The Ladies’ Union and other organizations have continued activities in the building to the present date (2018). In 2019 the building was used by the Lions Club according to a sign on the front that also declares declares: “Bowery Beach 1845”.

Dyer–Hutchinson Farm

[1148 Sawyer Road; N43° 36′ 18.38″ W70° 16′ 2.06″] The Dyer-Hutchinson Farm is one of the few, if not the only, eighteenth century farms that remain in Cape Elizabeth. Its centerpiece is a well preserved Federal period capestylehouse believed to have been built in the early 1790s. Vacant for several years, the house was acquired n the 1990s and stabilized. The property also contains a twentieth century building used for manufacturing wooden boxes.

William Dyer (1769-1844) was born in Cape Elizabeth, son of Benjamin and Elizabeth Higgins Dyer. On August 12, 1790, he married Thankful Higgins (1865-1849). Dyer began to assemble their homestead parcel in 1793 with the purchase of nine acres. Apparently construction of the house began about this time. Over the course of the next three decades Dyer acquired additional small parcels, several of which were salt marsh. The Dyers had two children: Leonard, born in 1794; and Zilpha, born in 1798. Upon their mother’s death, the farm descended to Leonard and Zilpha. In 1850 the Dyer farm was comprised of 20 acres of improved land, 25 acres of unimproved land, 1 horse, 4 milch cows, and 2 oxen.

In 1864 the Dyers sold the farm to Louisa A. Bennett, and in 1875 it was acquired by Edwin Hutchinson. In 1880 Hutchinson had not expanded the farm (its value had fallen), and he owned only one milch cow and two horses. The property later passed through his descendants to Margaret Hutchinson. During the property’s ownership by the Hutchinson family in the early 20th century, the existing box mill was built to the south of the house. Used to make wooden crates for produce and nursery stock, the box mill illustrates the pattern of home manufactures that had long been an important part of rural life in Maine. Unfortunately, little is known about either the volume of the output of this enterprise, its duration, or the destination of the boxes. However, the investment made in both the building and equipment clearly indicates that it was operated at a scale well beyond that needed solely for home use.

Although the permanent settlement of Cape Elizabeth began about 1720 and its first minister was settled in 1734, very few eighteenth century buildings survive to reflect this early history. In fact, an architectural survey of the town in 1992 concluded that the Dyer house was the oldest building in the western part of the town. Regardless of its rank among the town’s earliest buildings, however, the house has local architectural significance as a little altered example of a Federal period capestylehouse. In Maine, the one-and-a-half-story gable roofed cape was a ubiquitous building type throughout the 18th and the first half of the 19th century.

The major characteristics differentiating the capestylehouse from other house types are that it is invariably one-storied or has only a story and a half and that, in pre-Revolutionary Maine, it is always found with a central chimney”. Post-Revolutionary capestylehouses, particularly those built through the first years of the 19th century, are very much like their predecessors in overall form and the retention of central chimneys. However, notable modifications were introduced over time including a higher posted frame (which allowed for a taller facade and more interior headroom), larger windows, relocation of fireplaces and their attendant chimneys, and the adoption of fashionable architectural detailing.

In this context, the Dyer house clearly exhibits the features of a 1790s capestylehouse with its combination of central chimney, relatively low posting, symmetrical five-bay window pattern with central entrance, and Federal style interior woodwork.*

In 2017 the farm sign read: “The Old Farm, Christmas Place.” A substantial planting of thousands of Christmas trees covers the land behind the farm buildings. The farm offers “cut your own” trees, wreaths and other Christmas related items in its retail shop.

Portland Head Light

[Portland Head off Shore Road] Portland Headlight is one of the four lighthouses in whose construction was authorized by President Washington and that has never been rebuilt. The main section of the tower remains in the same form as when it was completed in 1790. First lighted 1791, the tower was built of stone taken from nearby fields and the shore.

The original structure was 72 feet high with a 15 foot lantern. In 1813, twenty feet was removed from the tower and in 1883 another 21 feet was removed. Due to public reaction, it was raised again with brickwork in 1885. In 1900, it was repaired using the original stones from the section that had been removed in 1813. The first keepers’ quarters was built in 1816. The current one was built in 1891 on the foundation of the old cottage.*

Ram Island Ledge Light Station

[Ram Island Ledge, Portland Harbor] This Light Station was established in 1905 to mark the hazardous and frequently submerged shoals at the northern side of the entrance to Portland Harbor. After the steamship California ran aground on the ledge in 1900, Congress appropriated funds in 1902 to begin construction of a light station on Ram Island Ledge. Work had not begun before the British schooner Glenrosa struck the reef during a heavy fog September 22, 1902. She was followed less than three months later by the fishing schooner Cora and Lillian.

[Ram Island Ledge, Portland Harbor] This Light Station was established in 1905 to mark the hazardous and frequently submerged shoals at the northern side of the entrance to Portland Harbor. After the steamship California ran aground on the ledge in 1900, Congress appropriated funds in 1902 to begin construction of a light station on Ram Island Ledge. Work had not begun before the British schooner Glenrosa struck the reef during a heavy fog September 22, 1902. She was followed less than three months later by the fishing schooner Cora and Lillian.

These mishaps clearly illustrated the need for a light and fog signal on the island in the busy shipping lanes near Portland. The light in the 77 fo0t tower operated for the first time on April 10, 1905. Sixty years later it was automated.**

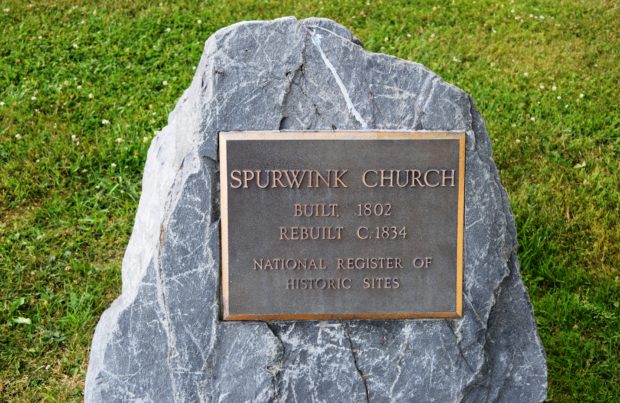

Spurwink Congregational Church

[Spurwink Avenue; N43° 34′ 46.01″ W70° 15′ 6.38″] Rev. Thomas M. Smith of the First Parish on the Neck, now Portland, was the first established minister for all of ancient Falmouth. He was ordained March 8, 1727, having graduated from Harvard in 1720. By an Act of the General Court May 7, 1733 the lands lying on the southerly side of Fore River were set off, and incorporated as the Second Parish. It was more commonly known by the early settlers as Purpoodock. In 1733 the parish voted to build a meeting house and November 10, 1734 Rev. Benjamin Allen was installed as minister.

[Spurwink Avenue; N43° 34′ 46.01″ W70° 15′ 6.38″] Rev. Thomas M. Smith of the First Parish on the Neck, now Portland, was the first established minister for all of ancient Falmouth. He was ordained March 8, 1727, having graduated from Harvard in 1720. By an Act of the General Court May 7, 1733 the lands lying on the southerly side of Fore River were set off, and incorporated as the Second Parish. It was more commonly known by the early settlers as Purpoodock. In 1733 the parish voted to build a meeting house and November 10, 1734 Rev. Benjamin Allen was installed as minister.

His successor was Rev. Ephraim Clark who was installed May 21, 1756. During his 45 years as pastor, a feud developed between Presbyterians and Congregationalists regarding church government. Cape Elizabeth (including present day South Portland)was incorporated as a district of Falmouth in 1765. In 1787 the Second Parish separated from the First. Rev. Elijah Kellogg was installed and was their sole pastor for 19 years. With a growing congregation of the Second Parish under Rev. Kellog, the South meetinghouse was built in 1802 at Spurwink as a branch of the First Congregational Church at 301 Cottage Road.

His successor was Rev. Ephraim Clark who was installed May 21, 1756. During his 45 years as pastor, a feud developed between Presbyterians and Congregationalists regarding church government. Cape Elizabeth (including present day South Portland)was incorporated as a district of Falmouth in 1765. In 1787 the Second Parish separated from the First. Rev. Elijah Kellogg was installed and was their sole pastor for 19 years. With a growing congregation of the Second Parish under Rev. Kellog, the South meetinghouse was built in 1802 at Spurwink as a branch of the First Congregational Church at 301 Cottage Road.

The present Spurwink Congregational Church was rebuilt in the 1830s on the site of the old meetinghouse. Cape Elizabeth separated from the area of present day South Portland in 1895, creating the two new towns. Spurwink Congregational became an independent church in 1935 after being associated with the First Congregational Church of South Portland for 133 years.

The present Spurwink Congregational Church was rebuilt in the 1830s on the site of the old meetinghouse. Cape Elizabeth separated from the area of present day South Portland in 1895, creating the two new towns. Spurwink Congregational became an independent church in 1935 after being associated with the First Congregational Church of South Portland for 133 years.

Cape Elizabeth built its own High School. The first graduating class of 1905 held its exercises in the Spurwink Church. Rev. Charles Rodway was the last minister to hold services during the summer months. The church was disbanded and the property transferred to the town in 1957.*

Two Lights

[off Maine Route 77] The lighted eastern (black capped) beacon is one of the most important along the northeast coast. Marking the entrance to Portland Harbor, it is a key navigation landmark. The twin towers also represent an era when double lights were used for ranging (finding one’s position at sea).

In 1811 a 50-foot rubblestone and lime mortar tower was built on the site of the east light by Revolutionary War General Henry Dearborn. In response to rapid growth in shipping, twin 65-foot stone beacons 129 feet above sea level were installed in 1827. Located 300 yards apart, the eastern tower showed a fixed light and the western, a flashing light 45 seconds on and off. In 1854, the new Fresnel lenses were added to both.

In 1855 the western light was discontinued. Protests, especially by fishermen who used the lights for triangulating the position of nets and traps, resulted in the light being restored in 1856.

In 1874, the stone towers were torn down and replaced by the cast iron structures now remaining. For economy in 1882 the western light was extinguished. Congressman Thomas B. Reed overturned the decision. Finally, despite protests, the western light was permanently extinguished in 1924. During the Second World War, it was stripped of its lantern and used as an observation post. In 1959, the tower along with 10½ acres, was sold by bid to the screen actor, Gary Merrill.* [See lighthouses.]

Richmond’s Island Archeological Site [Address Restricted]