Bangor’s architectural history is influenced by the great houses built in the boom years of the nineteenth century, with its resident lumber barons and its related commerce. The city’s role as a regional hub led to the development of such institutions as the commercial center at West Market Square, the theological seminary, and the mental health institute. Deborah Thompson’s work documenting these historic resources undoubtedly led to many being placed on the National Register.

84-96 Hammond Street

[also known as Albert and Edmund Dole Block; Albert and Edmund Dole Steam Mill Block] 84-96 Hammond Street has been used for the manufacture and sale of furniture in Bangor from the 1830s through the 1980s. Two contiguous blocks, linked by way of a passageway to a third freestanding building, this complex of brick and frame buildings has an important association with the early development of manufacturing enterprises in the city that catered to a burgeoning market for domestic products.

When market forces made local furniture making less profitable in the late 19th century, a new entrepreneur used the buildings to introduce modern retailing methods for selling and repairing furniture. The origins of the furniture business at 84-96 began in 1822 when the brothers Albert and Edmond Dole, both cabinetmakers, established a furniture factory on this site. The building that housed their operation was replaced in the 1830s by a three-story brick block that constitutes the lower section of 84 Hammond Street. By 1843, a major expansion of their enterprise had taken place with the construction of a steam mill, housed in the contiguous four-story frame block (88 Hammond). The business apparently produced elegant, low cost furniture of birdseye maple, mahogany, marble among other materials.

Between 1820 and 1860, the population of Bangor had grown exponentially. In 1855 the brothers established the Bangor Planing & Moulding Mill on Front Street. Both the expansion and the variety of their offerings reflect the population boom. No fewer than eight furniture manufacturers and dealers were also located in Bangor. By the mid 1880s, however, only two local furniture manufactures were still in business, one of which was the Dole Brothers.

In 1889 the Dole Brothers company was purchased by James A. Chandler and George H. Oakes. They discontinued the manufacture of furniture, while substantially enlarging the retail sales operation and maintaining the repair and upholstery services. By 1891 several alterations to the complex of buildings were made, including remodeling the storefronts of both 84 and 88 Hammond and adding new dormers to the latter. Further alterations were made within the next several years. The renamed Chandler & Co. remained in business until the mid 1920s. It was distinctive by being farther advanced and more modernized than many of the furniture concerns of the larger cities.

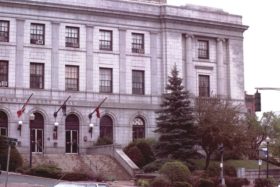

Adams-Pickering Block

[corner of Main and Middle Streets] The significance of the 1871 Adams-Pickertng Block is in its architecture and its architect. It was one of several grand mansard roofed commercial buildings designed by local architect George W. Orff for Bangor’s business district in the 1870’s. With its first story cast iron front and its Hallowell granite facade, the Adams-Pickering Block and its similar contemporaries were the most sophisticated Victorian commercial buildings in Eastern Maine.

[corner of Main and Middle Streets] The significance of the 1871 Adams-Pickertng Block is in its architecture and its architect. It was one of several grand mansard roofed commercial buildings designed by local architect George W. Orff for Bangor’s business district in the 1870’s. With its first story cast iron front and its Hallowell granite facade, the Adams-Pickering Block and its similar contemporaries were the most sophisticated Victorian commercial buildings in Eastern Maine.

The Bangor Fire of 1911, general urban change, especially urban renewal in 1968, destroyed most of the city’s 19th century business district. The Adams-Pickering Block is a rare survivor of downtown Victorian Bangor and Orff’s most distinguished remaining commercial work in Maine.

Orff, born in Bangor in 1836, learned carpentry locally. From about 1866 to 1869, he studied architecture in Boston, probably under Calvin Ryder (1810-1890), a native of Orrington, who had worked as an architect and builder in the Bangor region during the 1830s and 40s. Orff returned to Bangor about 1870 and established his practice. During his eight year career in the city, he designed both commercial and residential structures. His commissions included the Hatch Block, Emerson Block, and the Batchelder-Mitchell Block.

In 1878 he left for Minneapolis and had a successful practice with his brother F.D. Orff during the 1880s and 1890s. Along with other celebrated works, the J. Frank Collom Mansion in Minneapolis was one of the most important. Orff retired to Maine at the turn of the century and died in 1908.*

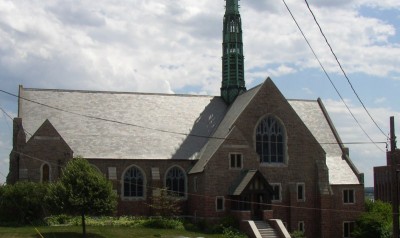

All Souls Congregational Church

[10 Broadway] The 1912 All Souls was squarely in the middle of Bangor’s leading residential district when built. Originally the church faced rows of stately houses built in the 1830s. This part of Broadway and State Street has completely changed: important houses have been replaced by shopping structures, gas stations, office buildings, and commercial blocks.

[10 Broadway] The 1912 All Souls was squarely in the middle of Bangor’s leading residential district when built. Originally the church faced rows of stately houses built in the 1830s. This part of Broadway and State Street has completely changed: important houses have been replaced by shopping structures, gas stations, office buildings, and commercial blocks.

All Souls Congregational was formed from the two Congregational societies that lost churches in the 1911 fire: the First (on this site) and the Third (on French Street). The two joined in the rebuilding and took the name All Souls. The church is an exceptionally creative Gothic building.*

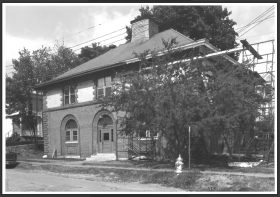

Bangor Children’s Home

[218 Ohio Street] Details of its many dormers and other evidence show it to be one of Maine’s first examples of the so-called “Stick Style,” popular in the post-Civil War era. Evidence of the social and humanitarian concerns of mid-Victorian America, the Home is the oldest philanthropic institution in Bangor. Its charter was granted by the Maine Legislature in 1839 as the Bangor Females Orphan Asylum.

[218 Ohio Street] Details of its many dormers and other evidence show it to be one of Maine’s first examples of the so-called “Stick Style,” popular in the post-Civil War era. Evidence of the social and humanitarian concerns of mid-Victorian America, the Home is the oldest philanthropic institution in Bangor. Its charter was granted by the Maine Legislature in 1839 as the Bangor Females Orphan Asylum.

Its first home on 4th street was supported largely by the Union Female Education Society founded in 1835. The present building was built with funds from the estate of Sarah Pitcher “for benevolent and religious purposes.” The Asylum was re-purposed to admit boys by the Legislature in 1866. The new building was dedicated on October 6, 1869, a portrait of Mrs. Pitcher being hung in the reception room.*

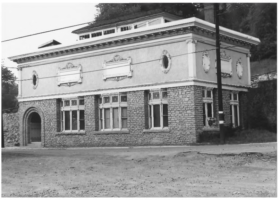

Bangor Fire Engine House No. 6

[284 Center Street] This Fire Station is significant as an exceptionally well designed institutional building by the important Maine architect Wilfred E. Mansur (1855-1921). It has been a beloved and functioning landmark in its neighborhood since it was built. Mansur also designed the State Street Fire Station (1897)and the Bangor Theological Seminary Gymnasium (1895). The Center Street Station is a classic design with an overall appearance of breadth rather than height, matching its location on a hill in district of middle class houses.

The Center Street Fire Station has been carefully maintained operated until 1987 when a new fire station was put into service. Over the years it became more and more difficult to accommodate modern firefighting equipment in a building designed originally for horse-drawn engines. It eventually passed into private hands where it could be re-used.* [Kirk F. Mohney photo]

Bangor Hose House No. 5

[247 State Street] Bangor Hose House No. 5 is a predominantly Romanesque Revival brick structure with a strong Colonial note provided by the Colonial Revival cupola on the square Romanesque tower. It shows Bangor architect Wilfred E. Mansur in his best Romanesque Revival idiom, which, as always, was tinged with other influences: here the Queen Anne in the building’s basic asymmetry, and the Colonial Revival in the cupola.

[247 State Street] Bangor Hose House No. 5 is a predominantly Romanesque Revival brick structure with a strong Colonial note provided by the Colonial Revival cupola on the square Romanesque tower. It shows Bangor architect Wilfred E. Mansur in his best Romanesque Revival idiom, which, as always, was tinged with other influences: here the Queen Anne in the building’s basic asymmetry, and the Colonial Revival in the cupola.

No. 5 served in its original capacity until 1993, when a new fire station was put into service. It became more difficult to accommodate modern firefighting equipment in a building designed originally for horse-drawn engines. Since closing, the building has been converted into a fire museum.*

Bangor House

[174 Main Street] In the booming 1830s, the profits of speculation in timberlands and enthusiasm at the extension of steamship service, which tied “Down East” to Boston, some merchants and speculators decided that the town of Bangor needed a physical symbol of its new social and economic position.

They established a corporation to create its first elegant public house. Taking a cue from Boston and its cultural influence, they carefully reproduced, on a smaller scale, the exterior design and interior arrangements of the palatial Tremont Hotel.

The Bangor House was completed during the latter part of 1834. A lavish public dinner on Christmas Eve marked its opening. The craftsmanship of the building and the luxurious furnishings in the public rooms and private chambers impressed many. Despite a number of alterations and additions, the original Greek Revival facade of the building, overlooking Union Street, remains intact.*

Bangor Mental Health Institute

[656 State Street] The Eastern Maine Insane Hospital, as it was initially known, is an impressive set of connected 3 ½ story brick buildings. It is composed of a central administration block flanked by long recessed wings. Originally conceived in its entirety much as it exists today, the complex evolved over nearly forty years as separate components were added to existing structures.

[656 State Street] The Eastern Maine Insane Hospital, as it was initially known, is an impressive set of connected 3 ½ story brick buildings. It is composed of a central administration block flanked by long recessed wings. Originally conceived in its entirety much as it exists today, the complex evolved over nearly forty years as separate components were added to existing structures.

The Hospital is one of the largest, least altered and most architecturally significant institutional buildings in Maine. Designed by John Calvin Stevens, it was built in stages between the years 1896 and 1935, opening in 1901. By virtue of its long staggered form and interior plan, the hospital embodies late 19th century medical theories concerning care for the insane.*

Since 2005 is has been known as the Dorothea Dix Psychiatric Center.

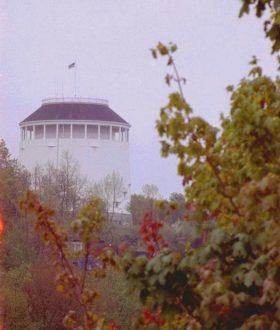

Bangor Standpipe

[Jackson Street] The Bangor Standpipe holds 1.75 million gallons of water on Thomas Hill. The tank is 50 feet high and 75 feet in diameter. Built in l897, it is the Bangor Water District’s oldest standpipe, used to help regulate Bangor’s water pressure in the downtown area and to provide storage for emergencies.

[Jackson Street] The Bangor Standpipe holds 1.75 million gallons of water on Thomas Hill. The tank is 50 feet high and 75 feet in diameter. Built in l897, it is the Bangor Water District’s oldest standpipe, used to help regulate Bangor’s water pressure in the downtown area and to provide storage for emergencies.

Built by Major James M. Davis, the well-known Bangor contractor employed more than twenty men and erected a portable saw mill and blacksmith shop on the site. The entire project took about six months. Beyond its primary function, the standpipe was designed to be an observatory from which to view the entire city of Bangor; which spread out below Thomas Hill, the highest point in the city. Along the inner wall of the exterior facade is a winding stairway which leads to a grand 12-foor wide promenade deck that encircles the building. From the deck a series of stairways lead to the roof, which is surrounded by a railing with four foot banisters.*

Bangor Theological Seminary Historic District

[Union Street] Six buildings in the district represent five architectural styles: two of the Federal style; one, Greek Revival; the Chapel, Italianate; one, Queen Anne; and one, Romanesque Revival. The First building was an 1824 chapel, destroyed by fire in 1829. The second, Old Commons of 1828, was first a student dormitory, then a faculty residence. A second dormitory, “Maine Hall,” followed in 1834.

[Union Street] Six buildings in the district represent five architectural styles: two of the Federal style; one, Greek Revival; the Chapel, Italianate; one, Queen Anne; and one, Romanesque Revival. The First building was an 1824 chapel, destroyed by fire in 1829. The second, Old Commons of 1828, was first a student dormitory, then a faculty residence. A second dormitory, “Maine Hall,” followed in 1834.

The Greek Revival “New Commons” provided more housing and an infirmary in 1836. In 1869 the Italianate Chapel was completed. The Professor Denio House (Queen Anne) arrived in 1893 followed by the Romanesque Revival Gymnasium in 1895. Moulton Library (modern brick and aluminum) completed the district in 1959.

The Seminary, one of the five oldest institutions for the training of ministers, missionaries and Christian educators in the United States, is the first such school in Maine.*

Battleship Maine Monument

[Junction of Main and Cedar Streets] Located in Davenport Park at the intersection of Main and Cedar streets, the Battleship Maine Monument is comprised of a triangular shaped granite structure to which is affixed the bronze shield and scroll work that was recovered in 1912 from the battleship USS Maine. The monument is surmounted by a bronze light standard that is crowned by an eagle.

[Junction of Main and Cedar Streets] Located in Davenport Park at the intersection of Main and Cedar streets, the Battleship Maine Monument is comprised of a triangular shaped granite structure to which is affixed the bronze shield and scroll work that was recovered in 1912 from the battleship USS Maine. The monument is surmounted by a bronze light standard that is crowned by an eagle.

Erected in 1922 by the City of Bangor in memory of Spanish-American War veterans, the Monument is in the shape of a ship’s prow. It is the largest and finest of the Battleship Maine memorials in the state, and one of about a dozen known Spanish-American War memorials in Maine.*

Blake House

[107 Court Street] The Blake Mansion’s Second Empire style with Italianate influences was a showplace when it was built in 1858 and remains so with minor alterations. Designed for William Blake, a wealthy Bangor merchant, this was one of the first Second Empire buildings in Maine. It epitomizes the style of living attained by Bangor’s upper class in the years just prior to the Civil War. That was before Bangor’s economy began to decline, as did her reputation as the “Queen City Of The East.”*

[107 Court Street] The Blake Mansion’s Second Empire style with Italianate influences was a showplace when it was built in 1858 and remains so with minor alterations. Designed for William Blake, a wealthy Bangor merchant, this was one of the first Second Empire buildings in Maine. It epitomizes the style of living attained by Bangor’s upper class in the years just prior to the Civil War. That was before Bangor’s economy began to decline, as did her reputation as the “Queen City Of The East.”*

Broadway Historic District

[bounded by Garland, Essex, State, Park and Center Streets] The Broadway area is a classic example of an upper class residential section in mid-19th century New England. The district is composed of a variety of architectural styles: Federal, Greek Revival and Second Empire residential structures, some designed as individual family dwellings, others as duplexes.

To Bangor’s successful merchants, Broadway was “a little bit of Boston” transposed into the center of a rough frontier boom town. If prosperity was gained from the stands of white pine on the Penobscot River, at least some of the profits were lavished on the street “that lumber built.”

No surprisingly, the leading citizens copied the styles of Boston since it was the source of most imports, both the material and cultural. Broadway became the showplace for Bangor’s elite: a symbol of the “Queen City’s” faith in a future of continued economic and cultural progress. Prominent residents included Governor Edward Kent, Congressman Charles A. Boutelle, and Lumber-Baron Samuel Veazie.*

Bryant, Charles G., Double House

[16–18 Division Street] This double house was built in 1836 by the important Bangor architect Charles G. Bryant. Built on speculation by the architect as a rental property, it reflects the great Bangor land boom of the 1830s,in which fortunes were amassed by speculations in timberlands and urban lots. Bryant joined the entrepreneurs during the boom. With the exception of a simple double house on Prentiss Street, it is the only one the type to survive with its elements intact. Its handsome trim beautifully carved wreaths were favored by Bryant. The is unique with its deeply recessed common portico. The very small scale of this ambitious design is quite unusual. Many of Bangor’s historic landmarks are on the scale of mansions. This small double house was intended as a residence for people of modest means, but it has the same brilliant design as some of the large houses designed by the same architect.*

[16–18 Division Street] This double house was built in 1836 by the important Bangor architect Charles G. Bryant. Built on speculation by the architect as a rental property, it reflects the great Bangor land boom of the 1830s,in which fortunes were amassed by speculations in timberlands and urban lots. Bryant joined the entrepreneurs during the boom. With the exception of a simple double house on Prentiss Street, it is the only one the type to survive with its elements intact. Its handsome trim beautifully carved wreaths were favored by Bryant. The is unique with its deeply recessed common portico. The very small scale of this ambitious design is quite unusual. Many of Bangor’s historic landmarks are on the scale of mansions. This small double house was intended as a residence for people of modest means, but it has the same brilliant design as some of the large houses designed by the same architect.*

Colonial Apartments

[51-53 High Street] All of the buildings on high street were originally built as high-style residences, between the early19th and early 20th centuries, with the apartment building as the last addition to the neighborhood. Built in 1919, the six-unit, three story, brick apartment building was designed in the Colonial Revival style by local architect Victor Hodgins. The building was stylishly designed both to fit into the neighborhood and to attract stable, middle-income occupants.

[51-53 High Street] All of the buildings on high street were originally built as high-style residences, between the early19th and early 20th centuries, with the apartment building as the last addition to the neighborhood. Built in 1919, the six-unit, three story, brick apartment building was designed in the Colonial Revival style by local architect Victor Hodgins. The building was stylishly designed both to fit into the neighborhood and to attract stable, middle-income occupants.

The construction of this building reflects changes in Bangor’s economy. The city had transformed from an internationally significant lumber port to a more diversified regional manufacturing, commercial, and service-oriented economy. These economic forces resulted in a change to the city’s social structure, with the expansion of the middle-class and, to a lesser degree, the working class. A small number of apartment buildings were constructed in the city as alternative to single-family homes. The six-unit building is unique in Bangor because it is the sole remaining early 20th century apartment house in the city that was designed for the middle class and has changed little. The Colonial Apartments helps to illustrate the social history of Bangor, as well as being a fine example of an architecturally stylish multi-family apartment house*

Connors House

[277 State Street] The Edward Connors House is one of dozens of large mansard-roofed mansions erected in Bangor in the years 1866-1875, a boom period for the lumber economy. Connors was a pivotal figure in the economic and social history of the era. The house is one of eight mansions erected (or remodeled from existing houses) within two building seasons (1866-1867), on two streets (Broadway and State), and which were virtually identical in configuration/decoration, differing only in minor design elements. They were the most elegant houses on the two most elegant avenues and were of so common a character as to inspire over a dozen simpler Bangor mansions by 1870.*

[277 State Street] The Edward Connors House is one of dozens of large mansard-roofed mansions erected in Bangor in the years 1866-1875, a boom period for the lumber economy. Connors was a pivotal figure in the economic and social history of the era. The house is one of eight mansions erected (or remodeled from existing houses) within two building seasons (1866-1867), on two streets (Broadway and State), and which were virtually identical in configuration/decoration, differing only in minor design elements. They were the most elegant houses on the two most elegant avenues and were of so common a character as to inspire over a dozen simpler Bangor mansions by 1870.*

Farrar, Samuel

[House, Court Street] The Samuel Farrar House is both historically and architecturally significant. Historically because it was the residence of one of Bangor’s leading businessmen during the boom of the 1830’s. Samuel Farrar grew up in Bloomfield and Dexter, dropped out of Bowdoin and Colby colleges, and in 1829 he began working for his father in his mills, stores, and lumbering. In 1834, the business was dissolved and Samuel took his $100,000 share and settled in Bangor.

[House, Court Street] The Samuel Farrar House is both historically and architecturally significant. Historically because it was the residence of one of Bangor’s leading businessmen during the boom of the 1830’s. Samuel Farrar grew up in Bloomfield and Dexter, dropped out of Bowdoin and Colby colleges, and in 1829 he began working for his father in his mills, stores, and lumbering. In 1834, the business was dissolved and Samuel took his $100,000 share and settled in Bangor.

In 1836, he built the house and entered the cultural and business life of Bangor as an owner of the Bangor House, president of the Mercantile Bank and as a municipal judge. He continued his interests in the Dexter Mills but in 1857 his enterprises failed and he was forced to sell his Bangor home. He moved to Wisconsin where he died suddenly in 1862. Architecturally this house is significant not only to the city of Bangor, but to the nation since it was an early work of one of America’s foremost architects, Richard Upjohn. A two story brick wing was added in 1846 by another of America’s great architects, Isaiah Rogers.*

In 2015 it had been linked to a modern addition under the name Kenduskeag Terrace described as “a community of 40 units of affordable elderly and disabled adult housing.”

Godfrey-Kellogg House

[212 Kenduskeag Avenue] The Godfrey-Kellogg House was built about 1847 for John Godfrey as a summer residence for his family. The significance of this complex of buildings lies in the fact that it is one of the finest surviving examples of Gothic Revival cottage architecture in the State. It has not been altered on the inside or the outside. Much of the original furniture, designed especially for this house, still remains. The grounds and buildings are well taken care of by the present owners.

On high cliffs overlooking Kenduskeag Stream, it once had a view of Morse Mill and the old covered bridge. The house includes an attached barn, a smaller barn, and a dog house, all in the Gothic Revival style.*

Grand Army Memorial Home

[159 Union Street] The Greek Revival G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic; the Union Army in the Civil War) Memorial Home was built about1840 for Thomas A. Hill, a prominent Bangor businessman. It was later occupied by Bangor’s first Mayor, the Honorable Allen Gilman, later by Samuel H. Dale, Mayor in 1863-66, 1871-72, who died in 1872. Mayor Dale’s portrait hangs in the house. President Ulysses S. Grant was entertained at a reception put on at the house by Mr. & Mrs. Dale during the two day celebration of the dedication of the European and North American Railway, October 18 and 19, 1871. Special china was ordered for the affair and extra interior decorating efforts were made.

[159 Union Street] The Greek Revival G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic; the Union Army in the Civil War) Memorial Home was built about1840 for Thomas A. Hill, a prominent Bangor businessman. It was later occupied by Bangor’s first Mayor, the Honorable Allen Gilman, later by Samuel H. Dale, Mayor in 1863-66, 1871-72, who died in 1872. Mayor Dale’s portrait hangs in the house. President Ulysses S. Grant was entertained at a reception put on at the house by Mr. & Mrs. Dale during the two day celebration of the dedication of the European and North American Railway, October 18 and 19, 1871. Special china was ordered for the affair and extra interior decorating efforts were made.

Three generations of Dale descendants occupied the house. It was bought by Dr. James F. Cox, prominent Bangor doctor, from the Walker family. In 1944, the Sons of Union Veterans acquired title and currently hold the building in public trust. The Bangor Historical Society (founded 1864) moved its museum collections to the second story in 1952 under agreement with the Sons. The architect for the building was Richard Upjohn.*

Great Fire of 1911 Historic District

[Harlow, Center, Park, State, York, and Central Streets] The District contains Maine’s most significant collection of early 20th century commercial buildings, and commemorates an urban rebuilding campaign matched only by Portland’s after its own conflagration of July 4, 1866. On April 30, 1911, a fire started in a dockside warehouse and laid waste almost half of Bangor’s commercial downtown: 100 business blocks, 7 churches and 285 houses.

Most of the burned buildings were wooden and crowded closely together. Bangor’s small fire department, although bolstered by units from as far away as Portland, scored no victories in fighting the blaze. The Bangor Fire was Maine’s last, and one of the most devastating, urban fires in Maine. Although only two people were killed, the city’s economy and services were paralyzed. The post office, customs house, telephone exchange, central fire station, telegraph station, library, and several banks had perished. Only 60% of the commercial loss was insured.

Nonetheless, the first new house began rising on burned ground within days, and on May 11th the first new commercial building was commissioned. The period of rebuilding was unprecedented in its use of national talents and the attention given to city planning. The result was Maine’s first, and most significant, completely 20th century urban space.

Bangor in 1911 was less dependent on lumber business than in the 19th century. The city’s economy serviced a large rural hinterland with cheap electric power provided by the pioneer plant of the Bangor Hydro-Electric Company at Veazie. It was not surprising that the first building commissioned after the fire, and one of the largest constructed in the rebuilding, was the Graham Block, owned by John R. Graham, president of the Bangor Hydro. Graham, who lost his own house in the fire, was one of the prime movers in the rebuilding, constructing seven new buildings, including a new house for himself, a new post office and two small factories, in addition to company buildings. The Hydro’s new electrical substation was one of the most progressive and modernistic designs of the rebuilding.

The downtown that was burned had been a mix of small businesses in wooden buildings that were beginning to share space with brick office blocks. The downtown that arose in the burned area was dominated by office buildings, with commercial space available only on the ground floors of multi-storied structures. The larger buildings were corporate owned, either by the Hydro, banks, trust companies, or real estate firms. Many of the ground-floor retailers (druggists, restaurateurs, grocers, beauticians) catered to office workers. The area had become an office or business district, distinct from a commercial district. It was an almost perfect representation of the “office-world” that was being created in America at the turn of the century.*

Hamlin, Hannibal, House

[15 5th Street] Though the birthplace of Hannibal Hamlin in the Paris Hill Historic District survives, this is the house which he purchased in 1862 while Vice President of the United States and which remained his home in Maine until his death almost thirty years later. Originally a flat roofed two story Italianate dwelling built in 1851 by William T. Billiard, it was altered in 1870 by Hamlin with addition of a Mansard roof, effectively adding a third story.*

[15 5th Street] Though the birthplace of Hannibal Hamlin in the Paris Hill Historic District survives, this is the house which he purchased in 1862 while Vice President of the United States and which remained his home in Maine until his death almost thirty years later. Originally a flat roofed two story Italianate dwelling built in 1851 by William T. Billiard, it was altered in 1870 by Hamlin with addition of a Mansard roof, effectively adding a third story.*

Hammond Street Congregational Church

Hammond and High Streets] Although technically an alteration of an 1833 Greek Revival Church, the Hammond Street Church is for practical purposes a handsome 1853 Italianate Church and celebrated Bangor landmark. The design was executed by the distinguished church architect John D. Towle of Boston.

Towle’s alteration or, more properly, redesign of the church was drastic and actually preserved only portions of the walls of the earlier ill-conceived structure, while removing the front and the towers. The walls were also raised and the building lengthened by about twenty feet. Towle’s work included impressive and important structures like the Berkely Street Congregational Church in Boston, the Congregational Church in Harwich, Massachusetts, the Old Grace Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and the Unitarian Church in Bangor.*

Towle’s alteration or, more properly, redesign of the church was drastic and actually preserved only portions of the walls of the earlier ill-conceived structure, while removing the front and the towers. The walls were also raised and the building lengthened by about twenty feet. Towle’s work included impressive and important structures like the Berkely Street Congregational Church in Boston, the Congregational Church in Harwich, Massachusetts, the Old Grace Church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and the Unitarian Church in Bangor.*

Jenkins, Charles W., House

[67 Pine Street] The 1846 Charles W. Jenkins House is an urban Gothic cottage. Unlike its more lavishly detailed contemporaries, it embodies the attributes of the Gothic Revival style through modest window hoods and a steeply pitched roof. The residential Gothic Revival in Bangor is a direct outgrowth of the construction of St. John’s Episcopal Church under Richard UpJohn’s supervision.

[67 Pine Street] The 1846 Charles W. Jenkins House is an urban Gothic cottage. Unlike its more lavishly detailed contemporaries, it embodies the attributes of the Gothic Revival style through modest window hoods and a steeply pitched roof. The residential Gothic Revival in Bangor is a direct outgrowth of the construction of St. John’s Episcopal Church under Richard UpJohn’s supervision.

Charles W. Jenkins was the nephew of a devout convert to Episcopalianism, James Jenkins, who was instrumental in settling the unpaid debts of St. John’s parish so that UpJohn’s new church could be consecrated. James probably influenced Charles Jenkins in his choice of style and architect. The house is a free adaptation of a Rural Gothic cottage. Its plan is unusual and has splendid interior spaces. There are few other Gothic cottages in Maine that produce the same a polished Gothic or “pointed” effect through such simple means.

Jonas Cutting–Edward Kent House

[48-50 Penobscot Street] This house, completed in 1837, was a dual residency for Edward Kent, Governor of Maine, and his law partner, Jonas Cutting who was later named to the Maine Supreme Court. Mr. Kent practiced law in Bangor and served as its Mayor during 1836 and 1837. He then served two terms as Governor in 1838 and 1840.

[48-50 Penobscot Street] This house, completed in 1837, was a dual residency for Edward Kent, Governor of Maine, and his law partner, Jonas Cutting who was later named to the Maine Supreme Court. Mr. Kent practiced law in Bangor and served as its Mayor during 1836 and 1837. He then served two terms as Governor in 1838 and 1840.

Designed in the Greek Revival style, the house is one of exceptional beauty. Beyond its architectural significance, and that one of its original owners became governor, the Cutting-Kent House is an excellent example of the style in which the lumber aristocracy of Bangor lived in the 1830s. This aristocracy controlled local politics and heavily influenced state affairs.*

Low, Joseph W., House

[51 Highland Street] Joseph W. Low is a rather shadowy figure in Bangor’s history. He is first referred to in the Bangor Directories of the 1840’s as a gentleman and businessman, suggesting he was quite wealthy. He left Bangor shortly after the Civil War for San Francisco. The 1857 Low House stands on one of the most beautiful locations in Bangor. It was built on the top of Thomas Hill, an important part of Bangor’s early urban planning.

[51 Highland Street] Joseph W. Low is a rather shadowy figure in Bangor’s history. He is first referred to in the Bangor Directories of the 1840’s as a gentleman and businessman, suggesting he was quite wealthy. He left Bangor shortly after the Civil War for San Francisco. The 1857 Low House stands on one of the most beautiful locations in Bangor. It was built on the top of Thomas Hill, an important part of Bangor’s early urban planning.

As originally intended, the Hill would be a showplace development for the elite of Bangor in the 1840s and 1850s. With most of the land in the Broadway area already taken, lumber baron Rufus Dwinel, as one of Bangor’s early mayors, instituted a tree planting project in the Thomas Hill area and encouraged the development of fine houses on the slopes of the hill. Dwinel’s aesthetic values are well rewarded by the view from the top of Thomas Hill which spreads the City of Bangor out below all the way to the Penobscot River. The entire view is framed by the trees that Dwinel caused to be planted in the 1840s.

The house itself is one of Bangor’s and Eastern Maine’s outstanding Italianate residences. It remains one of the finest examples of architecture and urban planning in those halcyon Bangor days before the Civil War. The sophisticated placement and design bespeak volumes of the varied talents available in an essentially frontier city. Designed by Harvey Graves of Boston, who executed several designs for churches in Bangor; including the Universalist in the 1860s and the Free Will Baptist in 1856, it remains his finest Bangor work.* [Richard D. Kelly photo]

Morse & Co. Office Building

[Harlow Street] Morse & Co. was Bangor’s outstanding example of the industrial commercial conglomerate typical of the late 19th century. “The great aim of the present day in business is concentration, you know”, said Walter L. Morse in 1896. When the firm was liquidated in 1948, Bangor’s Daily Commercial declared that “another era in the history of Bangor is ended. Once the greatest lumber port in the world, now the Queen City is a port without even a mill, let alone lumber”.

[Harlow Street] Morse & Co. was Bangor’s outstanding example of the industrial commercial conglomerate typical of the late 19th century. “The great aim of the present day in business is concentration, you know”, said Walter L. Morse in 1896. When the firm was liquidated in 1948, Bangor’s Daily Commercial declared that “another era in the history of Bangor is ended. Once the greatest lumber port in the world, now the Queen City is a port without even a mill, let alone lumber”.

In 1851 Llewellyn J. Morse and Hiram P. Oliver leased the 1814 Drummond sawmill on Kenduskeag Stream. Eight years later they purchased the mill. In 1858 the old grist mill was demolished, redesigned, and rebuilt for steam power. The partners purchased the McQuestion mill on the same stream in 1860.

For years the company was the largest salt grinder in New England. In 1901 their sawmill capacity produced between 40-50,000 board-feet daily. The firm handled 150,000 bushels of corn and 80,000 pounds of wool a year. They also harvested ice. Above all, Morse & Co. were known for their fine interior and exterior finishes. Their carefully crafted materials were used in Beacon Street town houses in Boston and summer residences in Bar Harbor. Locally, the company provided materials for rebuilding large areas in Bangor after the disastrous fire of 1911. For nearly one hundred years Morse & Co. was Bangor’s largest firm and maintained her lumbering tradition.*

Morse Bridge, Valley Avenue

[over Kenduskeag Stream] Once a well regarded covered bridge, it has been demolished.

Mount Hope Cemetery District

[U.S. Route 2] Opened in 1836, Mt. Hope may well be America’s second oldest garden cemetery. It has grown from fifty acres in the 1830s to three hundred acres in the 1970s. The earliest section is located on and immediately surrounding the large hill called Mt. Hope, containing many of the most historic features of the cemetery such as the following.

[U.S. Route 2] Opened in 1836, Mt. Hope may well be America’s second oldest garden cemetery. It has grown from fifty acres in the 1830s to three hundred acres in the 1970s. The earliest section is located on and immediately surrounding the large hill called Mt. Hope, containing many of the most historic features of the cemetery such as the following.

The Lodge (c.1900) is a pleasant turn-of-the-century structure in the then popular English Half-Timbered Style. It was built as the cemetery’s administrative office and as for a resting place for visitors. General Samuel Veazie Tomb (c.1840) is one of only two below ground tombs in the cemetery. It is marked by a handsome granite Greek Revival monument ornamented with wreaths and capped by an urn. The grounds are surrounded by a fence of stately granite posts, an intricate cast iron gate and railings.

Fred E. Bradford Stone (1861). The marble stone is an example of the rich Victorian carved symbolism found on markers throughout the older sections. Bradford died at 23, and his parents erected a stone expressing their grief. Above the inscription is a carved scene of Death breaking the column of life. Behind her stands Father Time with his scythe and hour glass. The broken column was a popular Victorian symbol for death at a young age.*

Penobscot Expedition

[Site, Address Restricted Bangor-Brewer] See Penobscot Expedition, a failed naval confrontation with the British during the Revolutionary War.

Sargent–Roberts House

[178 State Street] The Sargent-Roberts House an example of the historic preference for remodeling important Bangor houses in the newest styles. It incorporates in its mansard transformation much of what was apparently a very large, well built Federal house.

[178 State Street] The Sargent-Roberts House an example of the historic preference for remodeling important Bangor houses in the newest styles. It incorporates in its mansard transformation much of what was apparently a very large, well built Federal house.

Edward Sargent was one of a family of builder-architects active in Bangor from the beginning of the 19th century. His house was under construction in 1814, during the British occupation of Bangor. By the early 1830s, Sargent had turned from building to farming on the Dutton Road and his house passed to Amos M. Roberts, an important lumberman, later a banker. Sargent seems to have become prosperous and served as a community leader in the few years remaining before his death.

The Greek Revival alterations were made by Roberts. He apparently felt the house needed further upgrading to the current style right after the Civil War. The 1866 remodeling was partly a response to the wave of mansard construction that has just begun. A mansion-size house became the mark of the successful man (usually lumberman) in Bangor. Roberts, however, retained the Federal detailing of the rooms.

Benjamin S. Deane was probably the remodeling architect because of the bell-shaped gable, than originated in his work and the generally simple effect of the design. The curved roof was out of style, but often appears in Bangor mansards of the 1860s in imitation of the earlier mansards in the city. The features are virtually identical with those of Deane’s Conners-Crosby House at 277 State Street, the architect’s last known work.*

Smith, Zebulon, House

[55 Summer Street] The significance of the Zebulon Smith House lies in its architectural merits. Built in 1832, this house and the 1832 Charles Q. Clapp House in Portland are the two earliest known temple style Greek Revival houses in Maine. The Zebulon Smith House is not only important to the architectural history of Bangor but to Maine as well.*

[55 Summer Street] The significance of the Zebulon Smith House lies in its architectural merits. Built in 1832, this house and the 1832 Charles Q. Clapp House in Portland are the two earliest known temple style Greek Revival houses in Maine. The Zebulon Smith House is not only important to the architectural history of Bangor but to Maine as well.*

St. John’s Catholic Church

[York Street] St. John’s Catholic Church was built in 1855 by the Irish community of Bangor under the direction of Father John Bapst, a Jesuit priest. It was to be a symbol to the Irish community of their identity within the community as a whole. The builders were conscious of this need, for they remembered how their predecessors had been burned out and driven from the city by roving gangs of sailors and lumberjacks in the 1830’s. Two years before, their own priest had been ridden out of Ellsworth on a rail complete with a suit of tar and feathers.

[York Street] St. John’s Catholic Church was built in 1855 by the Irish community of Bangor under the direction of Father John Bapst, a Jesuit priest. It was to be a symbol to the Irish community of their identity within the community as a whole. The builders were conscious of this need, for they remembered how their predecessors had been burned out and driven from the city by roving gangs of sailors and lumberjacks in the 1830’s. Two years before, their own priest had been ridden out of Ellsworth on a rail complete with a suit of tar and feathers.

In 1855, Bangor was at the height of the Know-Nothing movement controlling the city council and a Baptist minister for a Marshall appointed to end the grog trade among the predominantly Irish owned grog shops on the waterfront. While the church was being built, Irish laborers stood guard against threats of the Know-Nothings to burn it to the ground. The church maintains much of its original flavor with its statue of St. Patrick to the left of the main altar and its high mahogany organ imported from Boston. The church stands in what was once the heart of the old Irish community.*

Symphony House-Isaac Farrar House

[ 166 Union Street] Isaac Farrar House was the first major work of architect Richard Upjohn. Handsomely proportioned and boldly detailed, the 1836 Greek Revival Isaac Farrar House shows Upjohn to be a talented designer in this style. Symphony House retains many of the features of the original house.

[ 166 Union Street] Isaac Farrar House was the first major work of architect Richard Upjohn. Handsomely proportioned and boldly detailed, the 1836 Greek Revival Isaac Farrar House shows Upjohn to be a talented designer in this style. Symphony House retains many of the features of the original house.

Isaac Farrar (1798-1860), for whom the house was built, came to Bangor from Dexter in 1836. He was a lumberman, merchant and president of the Maritime Bank of Bangor. Other notable people lived in the house. Charles B. Sanford, who lived there from 1865-1878, was proprietor of the Sanford Steamship Lines. Owen Davis, made it his home from 1882-1888 and was the owner and manager of the Katahdin Iron Works and the father of Owen Davis, Jr., author of the Pulitzer Prize winning play Ice Bound.

The House was a private residence until 1911. Owner Isaac Merrill made many changes to the house. He removed the wall around the property line, moved the entrance door forward and added a bay window above it. He added bay windows to the sides and another story was added. From 1911 until 1929, the house was occupied as a residence by the University of Maine Law School, called Stewart Hall. From 1929 to 1972 it was been used by the Bangor Symphony as the Northern Conservatory of Music and called “Symphony House”.* The building is now part of the Bangor YMCA.

Veazie, Jones P., House

[88 Fountain Street] Architect George W. Orff’s 1875 Jones P. Veazie House is a striking Second Empire style residence. It is one of only a handful of Orff’s residential commissions in Maine and the most intact and elaborately detailed. Jones P. Veazie (1811-1875) was a member of a prominent local family and was active in a number of businesses as well as founding in 1842 the Bangor Gazette. A long construction delay occurred, partially because of Bangor’s lingering economic depression of the early 1870s, as well as Veazie’s health. He died in 1875 before it was finished.

[88 Fountain Street] Architect George W. Orff’s 1875 Jones P. Veazie House is a striking Second Empire style residence. It is one of only a handful of Orff’s residential commissions in Maine and the most intact and elaborately detailed. Jones P. Veazie (1811-1875) was a member of a prominent local family and was active in a number of businesses as well as founding in 1842 the Bangor Gazette. A long construction delay occurred, partially because of Bangor’s lingering economic depression of the early 1870s, as well as Veazie’s health. He died in 1875 before it was finished.

Nearly a full year passed before his wife took possession of her house. She occupied it until her death. In 1917 the property was acquired by William McCrillis Sawyer, whose daughter and her husband made it their residence in the 20th century.*

Wardwell–Trickey Double House

[97–99 Ohio Street] Built in 1836 by the masons Oren Wardwell and Daniel Trickey, this well-preserved brick double house is among the finest buildings of the type in Bangor. Double houses made their appearance in Federal Bangor and remained a popular form in the city throughout the heyday of its land boom. Developers sought to make as much money from the land in the city as in the timberlands beyond it, and the city consciously imitated Bostonian forms. Double houses and terraces or row houses became less popular with the rise of the Italianate style in the 1850s. A number of finely proportioned side-by-side double houses, emulating the finest Federal double houses of Boston, were built in Bangor.

The Wardwell-Trickey Double House is a tremendously important building in the architectural history of Maine. It represents the type of divided, long-facade double houses with an ell, which provides a private facade to each tenement, a plan relatively rare elsewhere in Maine. The choice of brick over a frame exterior in the Double House reflects the training of Oren Wardwell and Daniel Trickey as masons. The house has two high-posted beautifully built brick basements that may be the finest of their era in Bangor. Its chimneys were very well built.

The Wardwell-Trickey Double House is exceptional, having been maintained as a rental property by major landholders in the city. It was kept virtually unaltered after the installation of front doors, hardwood floors, and two Eastlake cupboards at the turn of the 20th century. Its well-preserved interiors feature elegant Greek Revival details as well as original Federal wainscot and features rare in pretentious houses of this era.*

West Market Square Historic District

[West Market Square] West Market Square, originally known as Market Square, was the first open area market place in Bangor. As far back as 1834, at the incorporation of the City, the corner of Main and Broad Streets was listed in the City Directory as Market Square – to distinguish it from its new counterpart at the corner of Central, Harlow and Park Streets – which was known as East Market Square.

West Market Square remained the central focus of all business activities through most of the 19th and 20th centuries. The occupants of its buildings read like a Who’s Who of Bangor’s leading and most prosperous citizens. It was the location of doctors, attorneys, dentists, druggists, bookkeepers, booksellers, grocers, confectioners, jewelers and merchants of all kinds. At one point during the latter part of the 1800s, West Market Square was the location of at least four banks.

The West Market Square Historic District is a compact and cohesive grouping of six mid-19th century buildings and one building of the early 20th century, all commercial in nature, which are in an excellent state of preservation. All are survivors of the disastrous fire of 1911 that gutted most of the commercial area of downtown Bangor. In 1968 much of what was left was destroyed by urban renewal leaving this small cluster as the best of the remaining 19th century downtown.

Wheelwright Block

[34 Hammond Street] The 1859 Wheelwright Block in Bangor was Maine’s first Second Empire style commercial Building. The building survived both the Bangor Fire of 1911 and Urban Renewal in 1968 and has become a major landmark in the city’s business district. The Block was built by the firm of Wheelwright and Clark, clothiers. The Bangor Whig and Courier noted that the owners

[34 Hammond Street] The 1859 Wheelwright Block in Bangor was Maine’s first Second Empire style commercial Building. The building survived both the Bangor Fire of 1911 and Urban Renewal in 1968 and has become a major landmark in the city’s business district. The Block was built by the firm of Wheelwright and Clark, clothiers. The Bangor Whig and Courier noted that the owners

open their cloth and clothing warehouse on Thursday in the new and splendid five story block erected by them, and now about completed, on Taylor’s Corner, West Market Square. They occupy the entire first floor as a salesroom – being an area of nearly sixty feet square, with a height of about 15 feet – having an elegant iron front with heavy plate-glass windows upon the west and north sides of the building – and being finished in a most thorough manner, and in handsome and commodious style throughout.

[The owners] are now located in the most elegant building for business purposes in the State – and have one of the most extensive establishments in their line of business.

The designer of the Wheelwright Block, Col. Benjamin S. Deane, was a major architect and builder in 19th century Maine. Deane moved to Bangor in the early 1830s. In 1834 he joined the Bangor Mechanic Association, listed as a housewright. In December 1835, he was chosen by the building committee of St. John’s Episcopal Church to erect the church from Richard Upjohn’s plans.

Although the Wheelwright Block has been somewhat altered on its first and fifth stories, its very survival is remarkable. In 1911 it was spared in the great fire. Again in 1968 it escaped a large scale urban renewal project that leveled many of the city’s 19th century commercial structures.*

Whitney Park Historic District

[Roughly bounded by West Broadway, Union, Pond and Hayford Streets] The Historic District is a residential neighborhood of forty-two homes built between about 1850 and 1929. A small triangular shaped park at the south side gives the district its name. Ranging from modest mid-19th century capes to turn-of-the-20th century urban mansions, the district embraces one of the most intact and architecturally distinguished groups of houses in Bangor.

Built for a variety of businessmen and professionals, many homes depict the great accumulation of wealth generated from the city’s position as a world class lumber port during the second half of the 19th century. During the first two decades of the 19th century, Bangor’s growth moved at a modest rate. However, the village was entering a dramatic period of expansion that thrust it into international prominence as the world’s leading lumber shipping port.

By 1849 there were 63 manufacturers and dealers in lumber, in addition to three sash and blind plants and four coopers. The tremendous population growth and the prosperity that accompanied this period of development transformed the village into a thriving city (incorporated in 1834) with an attendant building spree that extended to commercial, public, religious, and residential construction.

By 1849 there were 63 manufacturers and dealers in lumber, in addition to three sash and blind plants and four coopers. The tremendous population growth and the prosperity that accompanied this period of development transformed the village into a thriving city (incorporated in 1834) with an attendant building spree that extended to commercial, public, religious, and residential construction.

The area within the present district boundary appears to have been undeveloped prior to the 1850s, though it may very well have been a pasture or simply an open lot. Nevertheless, as early as 1829 it was incorporated into the grid pattern street plan developed that set off nearly one-acre lots along Seventh Street (now West Broadway).

The area within the present district boundary appears to have been undeveloped prior to the 1850s, though it may very well have been a pasture or simply an open lot. Nevertheless, as early as 1829 it was incorporated into the grid pattern street plan developed that set off nearly one-acre lots along Seventh Street (now West Broadway).

In 1819 the Bangor Theological Seminary had relocated to the triangular campus that it continues to occupy immediately to the south of the district. Building in the neighborhood began about 1850 with the erection of a few late Greek Revival, Gothic Revival and Italianate style houses along Union, Hayward, Cedar, and Pond Streets. By the end of the decade most house lots that bordered these four streets had been occupied. The relatively modest scale and decorative treatment of these early houses suggest the neighborhood was initially populated by members of the middle class. This pattern continued in the 1860s and 1870s when additional homes were built on previously vacant lots.*

In 1819 the Bangor Theological Seminary had relocated to the triangular campus that it continues to occupy immediately to the south of the district. Building in the neighborhood began about 1850 with the erection of a few late Greek Revival, Gothic Revival and Italianate style houses along Union, Hayward, Cedar, and Pond Streets. By the end of the decade most house lots that bordered these four streets had been occupied. The relatively modest scale and decorative treatment of these early houses suggest the neighborhood was initially populated by members of the middle class. This pattern continued in the 1860s and 1870s when additional homes were built on previously vacant lots.*

Williams, General John, House

[62 High Street] One of the few Federal houses in Bangor and almost certainly the oldest brick house in the city, the General John Williams House is closely tied to the early history of the area. The lot at 62 High Street was part of the tract owned by James Dunning, one of the first proprietors in Conduskeag, as the region was then known. After passing through several owners, the lot was sold to John Williams in 1822 by Andrew Morse. In 1825 a house was first assessed against Williams.

Born in 1791, John Williams first appears in 1814 as a sergeant of artillery in the local militia under General Blake. The militia was ignominiously dispersed by the British, who then occupied Hampden and Bangor. In 1818 Williams, now a 2nd Lieutenant, was in charge of a unit honoring Commander-in-Chief John Brooks. By 1823 he had risen to the rank of Major and is recorded as insisting successfully on the proper observance of July 4th as Independence Day.

In 1824, in the saddle and harness business, Williams was listed among 29 leading businessmen and merchants in Bangor. Four years later he was placed in charge of the “Washington Engine”, a unit of the Bangor Fire Department, and in that year, 1828, received his commission as Brigadier General in command of the Bangor Militia. He was one of the four original incorporators of the Bangor Mechanic Association, founded for the cultural improvement of artisans and craftsmen. In 1830 he became its second president. Williams was appointed Register of Probate for Penobscot County in 1842 and served until 1849. He died in 1868.

In 1835 Rev. William Masea had acquired title to the property and lived there with Dr. John Mason, a well known Bangor physician. The house remained in the Mason Family until 1955.*

Additional resources

City of Bangor Historic Preservation Brochure Committee. “Bangor Historic Preservation Program.” Bangor, Me. City of Bangor. Summer, 2010. http://www.bangormaine.gov/image_upload/Historic_Brochure_Online_Version.pdf (accessed June 7, 2014)

*Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. Augusta, Me. Text and photos from National Register of Historic Places: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/text/xxxxxxxx.PDF and http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/photos/xxxxxxxx.PDF