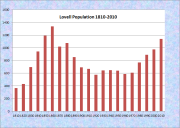

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 607 |

| 1980 | 767 |

| 1990 | 888 |

| 2000 | 974 |

| 2010 | 1,140 |

| Geographic Data | |

|---|---|

| N. Latitude | 44:11:36 |

| W. Longitude | 70:53:09 |

| Maine House | Dists 70,117 |

| Maine Senate | District 18 |

| Congress | District 2 |

| Area sq. mi. | (total) 47.9 |

| Area sq. mi. | (land) 43.2 |

| Population/sq.mi. | (land) 23.4 |

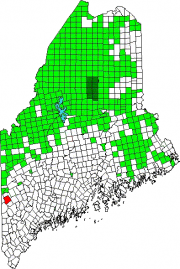

County: Oxford

Total=land+water; Land=land only |

|

[LUV-uhl] is a town in Oxford County, incorporated on November 15, 1800 from New Suncook Plantation. First settled in 1777, it set off land to Sweden in 1813.

The town is named for John Lovell (or Lovewell), the hero of the Battle of Lovewell’s Pond in 1725, in which Lovewell was killed but the remaining Abenaki people abandoned the area. The Pond is in nearby Fryeburg.

Kezar Lake, along with its Middle Bay and Lower Bay, dominates the middle of the town and supports the extensive summer recreation industry.

One of the lakeside lodges was owned by stage and screen star Rudy Vallee. Center Lovell, in the shadow of Sabattus Mountain, is the primary village, located on the shore of Middle Bay and Maine Route 5.

Kezar River Reserve is a 114-acre parcel managed by the Greater Lovell Land Trust. With frontage on the Mill Pond, it has a hiking trail and a canoe/kayak launch area. Access is from the east side of Route 5 about .8 miles north of Lovell Village. An old dam creates the Mill Pond on Route 93 near the town line with Sweden.

Sucker Brook Preserve protects a half-mile stretch of the brook, including Moose Pond where moose are frequently spotted. A diverse preserve, changing from pond to swamp to upland forest, it is home to a variety of plant and animal life including a colony of beavers, cardinal flowers and watercress, water lilies, speckled alder, sweet gale and button bush. Managed by The Nature Conservancy, it is located off Horseshoe Pond Road, near Kezar Pond.

The 1839 Kimball-Stanford House is home to the Lovell Historical Society. The first floor of the main house, on Route 5, is a museum.

Lovell is the birthplace on July 29, 1824 of Jonathan Eastman Johnson, who was the son of Philip C. Johnson, Secretary of State for Maine. He worked in a lithographic establishment in Boston in 1840 and after a year moved to Augusta, where he began making portraits in back crayon. Johnson continued his career in the Senate Committee Rooms at the U.S. Capitol, in Germany, and in New York City.

The Gazetteer of Maine had these observations on the local economy in the 1880’s:

At Lovell village, on [the Kezar River], near the southern part of the town, are several mills. There are also mills near the centre on the outlet of a small pond; and at North Lovell there is a steam-mill, manufacturing spools and long lumber. Other manufactures of the town are shooks, axe-handles and ox-goads, carriages and sleighs, cabinet work and coffins, boots and shoes, harnesses, etc. The small centres in Lovell, other than the principal ones already mentioned, are “Slab City,” “Sucker Brook” (the outlet of Horseshoe Pond), and “Cushman’s Mills,” on the outlet of Andrew’s Pond.

Form of Government: Town Meeting-Select Board.

Additional resources

Ann Beha Associates. Historic Property Plan: Eastman Hill Stock Farm. Boston, Mass. The Associates. 1992. [Maine State Library]

“Eastman Johnson (1824-1906).” Excerpt from a manuscript written by M. Elizabeth Boone for the New Britain Museum of American Art’s collection catalogue. 2003.

“Eastman Johnson 1824-1906.” Brief biography on Roughton Galleries Internet web site. http://www.crgalleries.com/action.lasso

Lovell, Maine: A Collection of Photographs and Snapshots. Prepared by the Lovell Historical Society. Lovell, Me. The Society. 1978. [University of Maine, Raymond H. Fogler Library, Special Collections]

*Maine. Historic Preservation Commission. Augusta, Me. Text and photos from National Register of Historic Places: http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/text/xxxxxxxx.PDF and http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/nrhp/photos/xxxxxxxx.PDF

Moore, Pauline Winchell. Blueberries and Pusley Weed. The story of Lovell, Maine. Kennebunk, Me. Starr Press. 1970.

Stone, W. Lawrence. Village Memories. Brewer, Me. Cay-Bel. c1986.

National Register of Historic Places – Listings

Photos, and edited text are from nominations to the National Register of Historic Places researched by Maine. Historic Preservation Commission.

Full text and photos are at https://npgallery.nps.gov/nrhp

Eastman Hill Rural Historic District

[Eastman Hill Road, East of Center Lovell Center Lovell] This District represents a microcosm of Maine agricultural land use history. Like many New England hill farms, its components were created in the early 19th century. Agriculture reached a peak around mid-century, then gradually declined. Unlike many 19th-century farms however, the Phineas Eastman, John Charles, and Isaac Eastman farms were not abandoned, but entered a new era as a gentleman’s agricultural estate. Robert Eastman’s acquisition of the three farmsteads reflected a regional transition from an agricultural economy to one based on tourism and recreation. The district remains intact and reflective of its entire history and evolution. While 19th-century farmsteads were once common throughout Maine, they are rapidly disappearing from the modern landscape. The district’s primary landscape significance derives from its association with land use patterns that have shaped the character of the Maine landscape from the 19th-century to the late 20th century.

On one level, the district is important as a common landscape, a collection of 19th-century hill farms that typify the broad patterns of New England agriculture, and Oxford County in particular. The configuration of fields, stone walls, and structures, which are the primary organizing elements of the landscape, still reflect the factionalism their 19th-century origins. This quality of the district is best illustrated by the small field enclosures, utilitarian outbuildings, and minimal ornamental plantings of the John Charles and the Isaac Eastman farmsteads.

The Phineas Eastman House is an example of the connected farmstead form. The connected farmhouse and barn is characteristic of northern New England in the period 1830 to 1860. This building type had its greatest concentration in Oxford County in the area around Lovell and evolved in response to both the climate and the mixed character of the 19th century New England agricultural economy. It was usually the most prosperous farms that were updated in this manner. The Phineas Eastman House developed this classic connected farmstead form with a one-story rear ell connecting to a gable-end barn with a sheltered south-facing dooryard quite early in its history. The other two farmhouses on Eastman Hill, serving as the homes of yeoman farmers, represent the most prevalent home types. The c. 1830 John Charles House, located to the north and across the road from the brick house, is a traditional one and one-half story, center-entry, center-chimney house. Popularly referred to as a “Cape”, this type predominated in the late-18th and early-19th-centuries, and was often recycled as the rear kitchen ell for a newer, larger, and more elaborate house. This house also has the attached ells and barn of a connected farmstead.* [James Higgins photos]

FIVES COURT

Fives Court 1924

The Fives Court is a specialized recreation building in Lovell. It was built 1924 as part of “Westways Kezar” a vacation and corporate retreat built by William Armstrong Fairburn. The complex was built on Kezar Lake near the White Mountains and a few miles from New Hampshire. Built in a Craftsman style with limited decorative details on the exterior, the one-story, one-room Fives Court interior shows distinct characteristics common to this rare type of sporting court.

The building is significant for the distinct form, proportions, plan, materials and structure which are characteristic of Rugby style courts and reflect its origins in English preparatory schools. The Fives Court retains the original elements of design, workmanship, materials, location, setting, feeling and association.

Hutchins, Moses, House

[junction of Maine Route 6 and Old Stage Road] The c. 1839 Hutchins house, now known as the Kimball-Stanford House, is an attractive, well proportioned, late Federal era farm house with a series of ells connecting the house to the New England style barn. Under the skin of clapboards and shingles, this house, as with so many in rural Maine, is an example of an evolving architectural approach that echoed the agricultural challenges and trends of the 19th century. Moses Hutchins built the main structure and barn. The first ell, and possibly the wood shed, was probably added shortly after Elbridge Kimball purchased the building in 1867. The upstairs of the ell became sleeping space and a workshop, while the downstairs included a new pantry and a kitchen with a cookstove. A new staircase was installed in the old kitchen to reach the chambers over the ell. Other interior changes occurred over the years.

The earliest incarnation of the barn was as a separate, three-bay English barn that faced the road. This barn would have been ample to house Moses Hutchins’ stock. Over time however, the barn evolved from the English form to the gable fronted New England form. Even at that time it was probably a mixed use barn, with horses, cows and hay, but on a larger scale. Additional remodeling in the early 20th century reflect additional technological changes. A post was removed, possibly to allow for the parking of vehicles and carriages.

Electricity was installed in the area by 1929. Additional vehicle storage facilities were added to the west side of the barn, the front shed for a car and the open rear shed for other agricultural implements.

The two-and-a-half story barn appears to have started its life as a three bay English barn with a roof line running from east to west. The original girts, and exterior posts and braces on the original southern wall are still present. A southern bay, stretching all the way across the front of the English barn was attached to the earlier structure and the roof re-oriented to run from north to south. The framing members are a combination of hewn and sawn timbers.*

In 2017 the Moses Hutchins House was home to the Lovell Historical Society.

Lovell Meeting House, 1796-1964

The Lovell Meeting House in the Oxford County town of Lovell is a building erected between 1796 and 1798 to serve as the town’s religious and secular assembly space. The site was first set aside in 1780 as the location for a meeting house, a training ground and a cemetery for the growing community. Originally built as a two-story building with a high pulpit and gallery, the building was reduced in height by at least three feet in the 1820s. In 1852 the local Congregational body built a new structure and the Meeting House shed its religious association and evolved into a civic structure. At times referred to as the Lovell Town House or Town Hall, this is still the present day building in which the local community gathers for town meetings, which are the semi-annual events that are the political backbone of small town democracy in Maine. In addition to serving as a polling place, the former Meeting House was outfitted with a stage at the turn of the20th century, and has been the location of various forms of entertainment and recreation. The Lovell Town House was recognized for its local role as the seat of civics, politics and government, starting in 1796 when the building was erected.

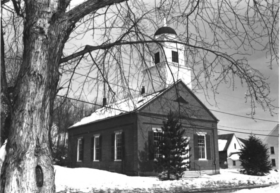

Lovell Village Church

[Church Street] The charming Lovell Village Church was built and probably designed by Ammi Cutter, a brick maker and mason of wide-spread reputation in northern Oxford County. The the circumstances surrounding the erection of the church has much to say about the slavery controversy in Maine more than a decade before the Civil War. Since the founding of the Congregational Church in Center Lovell in the early 1800s, parishioners from the entire town had attended services in the town hall in that village.

In 1841, Moses Heald, a member, moved to Georgia and transferred his membership to a church in that state. Although there for a comparatively short time, he did become a slave owner. When he returned to Lovell, having sold his slaves, he wished no rejoin the church. The resulting debate taking place over six church meetings as to whether, having been a slave holder, he should be allowed to return, divided the church deeply. The result was that Mr. Obed Stearns, leader of the opposition that was centered among the Lovell Village members, began a movement that led to the erection of the Lovell Village church. In response the members in Center Lovell built one of their own. Clearly the question of slavery was a live and controversial issue even in the smallest Maine villages nearly twenty years before the actual outbreak of the Civil War.

Maine Archaeological Survey site 21.26, Native American Petroglyphs and Pictographs of Maine, Address restricted.