Also see: Browntail Moth.

Deer ticks are small, about 1/8 of an inch. They may reach 1/2 inch if swelled with blood.

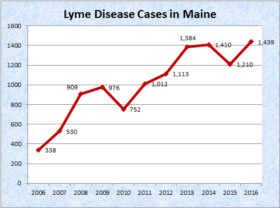

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium transmitted to a person through the bite of an infected deer tick. (Actually not an insect but, with eight legs, an arachnid.) Symptoms include the formation of a characteristic expanding rash at the site of a tick bite 3-30 days after exposure. This rash occurs in 80% of patients. Fever, headache, joint and muscle pains, and fatigue are also common during the first several weeks. Later features of Lyme disease can include arthritis in one or more joints (often the knee), Bell’s palsy, meningitis, and other rarely, if ever, fatal maladies. Lyme disease gets its name from a small coastal town in Connecticut – Lyme.1

To Prevent Tick Bites

- Wear light-colored clothing (to easily detect ticks) and tuck pant legs into socks.

- Use a tick repellant such as DEET on skin or permethrin on clothing.

- Inspect yourself and your clothes closely for ticks.

- Shower and wash clothes as soon as possible.

Prompt removal of attached ticks is extremely important! Ticks need to be attached for 36 hours to transmit Lyme disease. Ticks attach at body folds, behind the ears, and in the hair.2

Biting insects are as much a part of Maine as the rocky coasts and the vast forests. There are four types of biting insects in the state: mosquitoes, two types of biting flies and no-see-ums.

The largest populations of these “bloodsuckers” are found during the late spring and early summer, but winter is the only time that human blood is safe from these predators.

Generally, dark colors attract biting insects. A combination of clothing (long sleeves and light colors) and a little repellent is a good avoidance strategy.

The most annoying of the biting insects is the black fly because of its large numbers in late spring and early summer and the open wounds it leaves on its victims. To feed on blood, the black fly first cuts the skin open, adds an anti-coagulant and then slurps up the blood. Only female black flies will bite humans, using the blood for both food and egg production.

For some the bite of a black fly will cause an allergic reaction that can range from localized swelling or swollen glands to difficulty with breathing. An individual’s reaction to the bites tends to become less severe the longer he or she is exposed to the flies. Black flies lay their eggs in running water, and the immature flies develop in the water. However, once the flies grow wings, they can travel several miles from their original home. Most black flies produce only one generation each year, but some will produce several generations until the first freeze in the fall.

While black flies are more likely to be found in more remote areas, mosquitoes can be found wherever there is standing water. Mosquitoes are present throughout the warm months, but because the number of wet areas decreases during the summer, the number of mosquitoes also drops. Like the black fly, only female mosquitoes bite, but the blood they draw is used exclusively for egg production. Mosquitoes are drawn to humans and other mammals by the carbon dioxide given off by their bodies.

No-see-ums, also known as biting midges, are small insects that can fly through most screens on windows and tents. Their bites usually go away quickly and feel like little pin pricks. They breed in moist soils and can be found throughout the warm months. No-see-ums’ most active feeding period is right around dusk. Because they are evening feeders, no-see-ums are less likely to be affected by the colors their victims wear. Richard Dearborn, a survey entomologist for the Maine Forest Service, said common insect repellents have little effect on no-see-ums.

The last human predator in Maine’s insect world are the larger flies, popularly called horse, deer and even moose flies. These larger biting flies are found throughout the summer. Unlike the black fly, larger fly eggs hatch in moist soil and are most common in July and August. These flies can range in size from 1/4 inch in length up to one inch with most averaging around 1/2 inch.

Only female flies feed on blood, and only one-third of the more than 70 species normally feed on humans, but all have the capability. The blood is used by the fly for both egg production and for food. The larger flies produce only one generation every year, and for some species it is every two years. The eggs are usually lain on vegetation above moist soil and hatch that same year. The larvae will live until the next year in the soil and emerge the next summer to seek their prey.

Source: Maine Almanac and Book of Lists. p. 131.

Additional resources

Burian, Steven K. Mayflies of Maine: An Annotated Faunal List. Orono, Me. Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine. 1991.

2“CAUTION! Deer Tick Habitat.” [poster] Maine Medical Center Research Institute with financial assistance from the Maine Department of Conservation.

Forest & Shade Tree Insect & Disease Conditions for Maine: A Summary of the 2007 Situation. Augusta, Me. Maine Forest Service [i.e. Bureau of Forestry]. 2008.

Ismail, Amr A. (Amr Abdelfatta). Honeybees and Blueberry Pollination. Orono, Me. University of Maine Cooperative Extension Service. 1999?

LaBonte, George A. Field Book of Destructive Forest Insects. Augusta, Me. Division of Entomology, Maine Forest Service [i.e. Bureau of Forestry], Dept. of Conservation. 1980.

1“Lyme Disease.” Maine Department of Health and Human Services. At http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/boh/ddc/epi/vector-borne/lyme/. (accessed 10/17/2010)

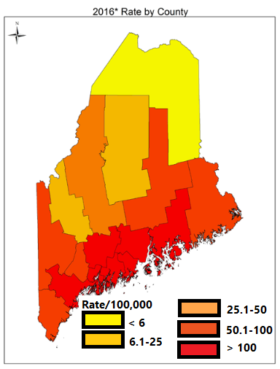

Maine. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to Maine Legislature: Lyme and other Tickborne Illnesses. February 1, 2017. http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-borne/lyme/documents/Lyme-Legislative-Report-2017.pdf (accessed April 27, 2017)

Maine. Forest Commissioner. Insect Primer. Augusta, Me. 1974.

Maine. Scientific Survey. Annual Report upon the Natural History and Geology of the State of Maine. Augusta. 1861-62. (available at Bangor Public Library and University of Maine, Fogler Library, Special Collections)